It is that time of the year when millions of students across the country are picking institutions and courses they want to pursue. According to AISHE 2020-2021, the total enrolment of women in higher education is around 49%, almost on a par with men. The Ministry of Education data further indicates that female Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) has overtaken male GER since 2017-18. These numbers certainly gladden the heart, especially given that women were not allowed admission to most higher educational institutions almost a century ago.

It is common knowledge that girls’ education was one of the major areas of focus in the 19th century for social reformers as well as the British government. One would assume that the ripple effect would have led to the entry of women into higher education. But it wasn’t as simple as that. Women who wanted to pursue higher education were expected to study in women’s colleges, which scarcely existed, and most reputed universities and colleges didn’t enrol women students. The doors of some of these institutions opened only due to the sheer determination of the women who wanted to study there.

In my research for a book on women in India’s Constituent Assembly, I came across some interesting anecdotes about the struggles and challenges these women leaders endured in their pursuit of higher education. Let me share some examples.

A letter to Tagore

Established in 1901, Tagore’s residential school at Santiniketan had gained a high status in society. Building on that premise, a university called Visva-Bharati was established in 1921. It was a strictly male environment and didn’t have provisions for female students. Undeterred by this technicality, a spirited teenager Malati Choudhury, who later became a famous social worker, wanted to study there.

She directly wrote to Tagore, a family friend, requesting admission to the institute. This unprecedented plea made Tagore think. He then decided to open a girls’ hostel to accommodate female students and asked Malati’s mother to be the superintendent of the hostel. She, of course, accepted the offer and Malati’s desire to study at Santiniketan led to the entry of the first girls’ batch of 1921-22.

Another woman revolutionary, Leela Roy wanted to pursue a Master’s degree from the University of Dhaka, established in July 1921, but it was open only to male students. Determined to secure admission, Leela petitioned the university authorities. Her request put the administration in a dilemma — how would a lone woman adjust on a campus of 800-odd men. They denied her plea, which then stirred her activist spirit. She went to Vice-Chancellor P J Hartog and demanded an environment for co-education. Impressed by Leela’s persistence, he set up evening classes for her and three other young women who had made similar requests to the authorities.

In western India, Hansa Mehta was one of the first women enrolled in Baroda College (now known as the Maharaja Sayajirao University), between 1913 and 1917. Her father was a professor who taught there, a factor that could have aided in breaking the barrier to admit Hansa and the two other women students. Still, the college atmosphere was hostile and unfriendly towards the young women, as the male students and faculty weren’t used to having women students around. The women had to self-censor in terms of appearance and mannerisms throughout their time there.

A similar ordeal was faced by Sucheta Kriplani, the first woman Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, during her student years at St Stephen’s College, Delhi. The only woman in the class of Master’s students, she was picked on by her male classmates. The titters died down when she outscored them on all but one paper. She wrote in her autobiography, “I heaved a sigh of relief. I had no longer to bother about the sniggering of the boys. My reputation in St. Stephen’s was established.”

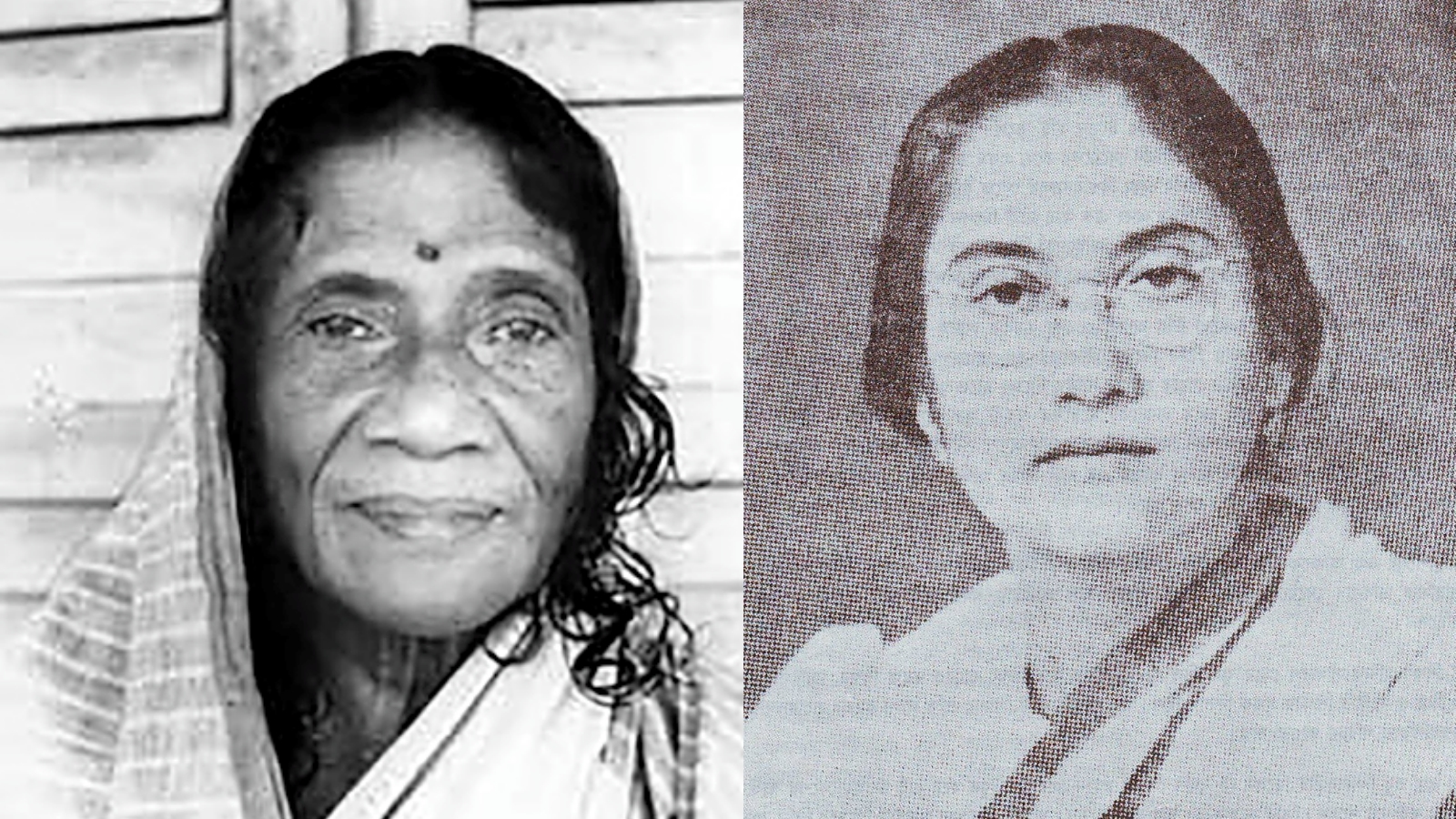

First Dalit women to go to college

It wasn’t easy being women in these highly masculine and patriarchal set-ups. Additionally, one must also recognise the intersectionality of the challenges faced by women from marginalised communities. Being one of the first Dalit women to go to college in Cochin, Dakshayani Velayudhan faced discrimination not just from her peers but also from her teachers. A student of BSc Chemistry, she had to learn crucial practical experiments from afar because one of the upper-caste teachers did not show her any of them. She graduated in 1935 in the second division.

Today, the barriers to accessing education for women students have diminished significantly. Much of this credit goes to women leaders from our history who used their grit and relative privilege to open the door for generations of women who came after them. Hopefully, their stories will motivate our youth to do away with the residual patriarchy that still lurks in the hallways of our higher educational institutions. After all, sometimes it only takes one person to change the course of history.

Angellica Aribam is a political activist and the lead author of the book, ‘The Fifteen: The Lives and Times of the Women in India’s Constituent Assembly’