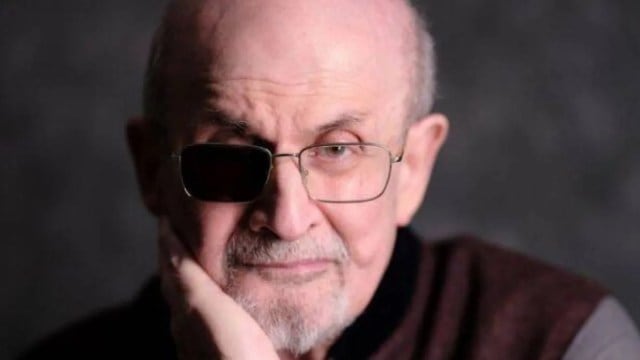

In Knife, Salman Rushdie’s remarkable account of finding his way back to life after an assassination attempt in upstate New York in August, 2022, love arrives with the tenderness of a saviour. It does so when he is “actively, determinedly, not looking for it” and renders him “powerless to resist”. He has four marriages and several relationships behind him, each ending in heartbreak and bruising derision. But when Rushdie is swept off his feet again, his exhilaration has the wonder of first love. He is introduced to the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths at a PEN event in New York. Later, he bumps into her again at the after-party. She is 30 years his junior but he is utterly smitten. He invites her to watch the city lights with him from the rooftop. Following her out, in his eagerness, he walks into the sliding glass door, almost knocking himself out from the impact. She offers to drop him home and they speak through the night.

In the five years that follow — through the pandemic, marriage and till the attack on him — his life is an idyll. There is a surfeit of happiness, “just by itself, enough”. “It was clear to me that this was not just a relationship of equals — rather, it was one in which I was by some distance the less equal party. Even better than that: It was a relationship not of competitiveness but of total mutual support,” he writes in Knife.

There is a touch of the maudlin here, but the Rushdie one encounters in these pages is a romantic. In the face of persistent hate, love is his rebellion and his refuge.

Yet, the leitmotif of literary coupledoms — between Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, or Elizabeth Jane Howard and Kingsley Amis, for instance — has tended to be one of passionate intensity and tumultuous falling apart. “In the marriages of celebrated literati throughout history, husband is to fame as wife is to footnote,” writes Carmela Ciuraru in Lives of the Wives: Five Literary Marriages (2023), in which she explores the relationship between Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia; Howard and Amis senior; Elaine Dundy and theatre critic Kenneth Tynan; Patricia Neal and Roald Dahl, and Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall.

There are, of course, exceptions. In 1978, a year after they met, Gerald Durrell wrote to Lee McGeorge, a PhD student at Duke University whom he’d marry a year later, a note confessing his feelings: “To begin with, I love you with a depth and passion that I have felt for no one else in this life and if it astonishes you, it astonishes me as well.”

As romantic admissions go, this would rank as a soul-tie but Durrell, who’d been married once before, tempered it with caution: “Don’t let this become public but well, I have one or two faults. Minor ones, I hasten to say… I am inclined to be overbearing. I do it for the best possible motives (all tyrants say that) but I do tend (without thinking) to tread people underfoot. You must tell me when I am doing it to you, my sweet, because it can be a very bad thing in a marriage… Second blemish… not so much a blemish of character as a blemish of circumstance. Darling, I want you to be you in your own right, and I will do everything I can to help you in this. But you must take into consideration that I am also me in my own right and that I have a head start on you… what I am trying to say is that you must not feel offended if you are sometimes treated simply as my wife… I am an established ‘creature’ in the world, and so — on occasions — you will have to live in my shadow.”

It’s hard to tell the role his candour might have played in what turned out to be a happy marriage. But the troublesome legacy of writerly romances is that they rarely wind up in forever-and-ever-afters. Writers can be capricious beings, used to the spotlight that comes from being “established creature(s) in the world”, their personal lives following the ebb and flow of their creative fortunes and fragile egos. Love can often be fraught territory.

In Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life (2023), for instance, Anna Funder writes of Eileen O’Shaughnessy, writer George Orwell’s wife, who gives up her university degree to move to the countryside with her husband so he could pursue his literary career. Despite her own intellectual promise and the contributions she made to his writing (among other things, she edited, typed and critiqued his manuscripts and was supposedly the one to have suggested that Orwell write 1984 as a fable), it is a fundamentally unequal relationship. The “motherload of wifedom” that she bears does not stop Orwell from being unfaithful to her or from edging her out of their story with mere lip service. There is a loneliness to the union that comes from Orwell gliding over O’Shaughnessy’s place in his life and literature.

Loneliness has no place in Rushdie’s story. As he lies bleeding after the attack in Chautauqua, in that moment of violent rupture, it creeps upon him briefly, the physical distance between him and everyone he loves — his wife, sons, sister and nieces. Does impending tragedy alter the nature of one’s affections, clarify it with a greater urgency? Who can tell? Rushdie knows, with that strange, intuitive fatwa-defying, free-speech endorsing courage, that this is no way to die. That he would, instead, live in love.

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com