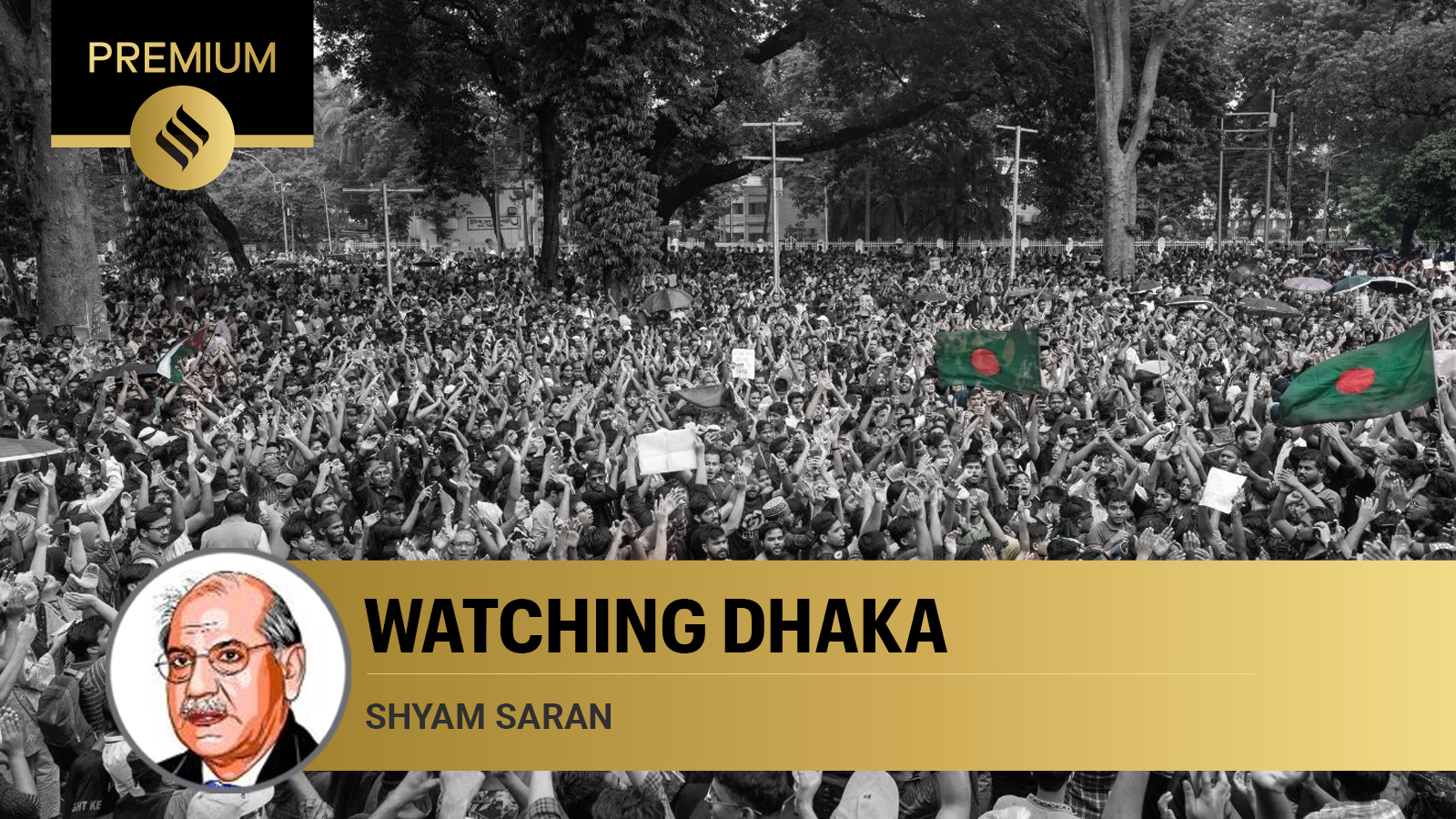

The old order in Bangladesh has changed irreversibly and India will have to adjust to the change. A student protest against reservation morphed into a wider people’s movement against the increasingly autocratic and corruption-ridden rule of Sheikh Hasina. She has resigned and left the country and may take shelter in India. India should not deny her that. The Bangladesh Army appears to have taken charge though it has promised an interim government of “stakeholders” to pave the way for free and fair elections. Whether the protests will die down and the current unrest on the streets of Dhaka will be stemmed remains to be seen.

Sheikh Hasina’s rule was tolerable as long as the Bangladesh economy, centred on export of garments, was registering sustained growth and delivering on jobs and better living standards. However, the pandemic in 2020 and a slowing global economy, thereafter, hit the garment industry badly. A toxic mix of economic distress and the increasingly high-handed behaviour of the government and its Awami League party members turned a student protest into a full-scale anti-government people’s movement. Whatever decision Delhi takes concerning Sheikh Hasina’s possible stay in India, it must acknowledge that the people of Bangladesh have rejected an unpopular government and have the legitimate right to chart their own future.

This reminds me of 2006, when a people’s movement in Nepal gathered in the capital, Kathmandu, asking for an end to an increasingly dictatorial monarchical rule and restoration of multi-party democracy. India chose to align itself with popular sentiment in Nepal, declaring that it would respect whatever choice the people of Nepal made. This defused a potentially ugly situation since there was a widespread belief in Nepal that India was pro-monarchy. In the current evolving situation in Bangladesh, India as a vibrant multi-party democracy, should be seen as supporting the expression of popular will in a sensitive neighbouring country. This may also go some way in diluting the negativity born out of the admittedly close relations between the two governments and Indian and Bangladesh leaders.

Since 2009, the rule of Awami League leader, Sheikh Hasina, helped transform India-Bangladesh relations into a success story for India’s neighbourhood policy. The gains for India are significant. Bangladesh is no longer a sanctuary for elements hostile to India. This has helped bring relative peace to India’s Northeast. Connectivity projects between the two countries, including the restoration of cross-border river transportation, have advanced mutually beneficial economic integration. India has also emerged as a major source of power for Bangladesh, and this has been a critical factor in that country’s economic success.

A benign political dispensation in Dhaka provided the opportunity to put in place long-term interdependencies, which should survive a change in government. India should express its readiness to expand the bilateral economic engagement with a successor government. The temptation to brand the ongoing political change as anti-India or anti-Hindu should be avoided.

There is no doubt that both Pakistan and China will see the political change in Bangladesh as an opportunity to challenge India’s presence in the country and try to tar it with a pro-Hasina brush. This may even get some traction. However, India should bide its time and allow the logic of economic interest to assert itself. There are also strong people-to-people relations and close cultural affinities which are assets that have prevailed even when political relations have been strained and a negative political sentiment has been deliberately stoked in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh has a border only with India, except for a short stretch with Myanmar. This is a challenge, but it is also a strategic advantage. Delhi should let the current storm dissipate, be cautious and discreet in its reactions. A new dispensation in Dhaka may adopt hostile policies similar to what one witnessed when Mohamed Muizzu took over as the President of the Maldives. The Indian reaction was mature and kept the door open for the continuance of close and mutually beneficial ties through discreet engagement and dialogue. Relations have returned to an even keel. That is a good template to follow.

It is not clear who will constitute an interim government. Will the Bangladesh National Party and the Jamaat-e-Islami be represented? Will the Army also insist on being part of the government or will it operate at arm’s length? Should the unrest and street violence continue despite Sheikh Hasina’s exit, will the Army take on a direct political role? After all, it has done so in the past. Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s statue in the capital was vandalised. Does that presage a wholesale repudiation of his legacy as leader of the liberation of Bangladesh and its establishment as an independent nation?

There are sections within Bangladesh society who rejected the separation from Pakistan. Even though that history cannot be reversed, will the posture towards India once again become sharply adversarial as has happened in the past, when Bangladesh was led by such elements? All these are questions to which there are no ready answers and should not influence Delhi’s policy in this fluid situation. The situation in Bangladesh is changing rapidly. Several questions will remain to be answered in the coming days. The time-tested diplomatic response to this should be that we are waiting and watching to see how things will develop and to reiterate our friendly sentiments for the people of a close and important neighbour. So let us wait and watch.

The writer is a former foreign secretary