Dec 27, 2024 16:11 IST First published on: Dec 27, 2024 at 10:13 IST

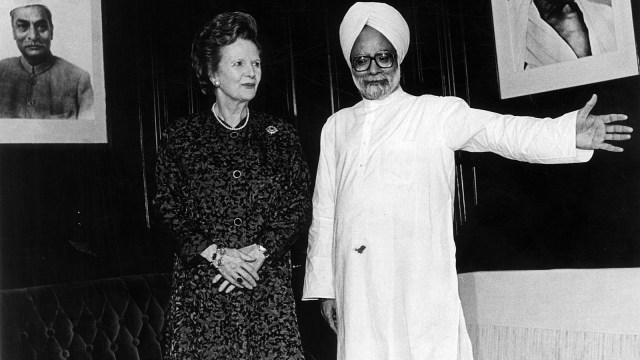

Manmohan Singh’s lasting legacy would probably be more as the Union Finance Minister who ushered in economic reforms during the early 1990s, than as India’s fourth longest-serving Prime Minister from May 2004 to May 2014. What began with a two-step devaluation of the rupee in early-July 1991 was followed by the dismantling of a four-decade-old regime of industrial licencing, state-led planning and public sector dominance, price and import controls, and near-autarky. Singh, as finance minister under P V Narasimha Rao during June 1991-May 1996, was undoubtedly the architect of these reforms that were about liberalisation and globalisation. The former involved dispensing with government approvals for starting and expanding factories or importing capital equipment, making it easier to raise monies from capital markets, and opening up a host of sectors – from telecom, power, civil aviation, highways and ports to banking, insurance and cable television – for private investment. The latter allowed Indian firms access to global markets, finance and technology, which was complemented by easing barriers on imports and foreign direct as well as portfolio investment. Liberalised rules for remittance of foreign exchange, lifting of pricing controls on industries such as steel, cement and aluminium, and closing down the offices of the Directorate General of Technical Development, Chief Controller of Imports and Exports and the Controller of Capital Issues were further signifiers of a new language – one welcoming of private initiative.

The firm conviction behind the moves was evident in Singh’s first Budget speech of 1991-92, where he underlined how “we have now reached a stage of development where we should welcome, rather than fear, foreign investment” and that “our entrepreneurs are second to none”. And, of course, the memorable closing lines where he invoked Victor Hugo to declare that the emergence of India as a major economic power was an idea whose time has come: “Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake”. It’s a different thing that annual GDP growth during his five years as finance minister averaged a mere 5.1 per cent. It accelerated to 5.9 per cent over the subsequent eight years from 1996-97 to 2003-04. The real fruits of reforms were borne during Singh’s tenure as Prime Minister. Those 10 years from 2004-05 to 2013-14 not only saw an average GDP growth of 6.8 per cent, but gross capital formation or the investment rate in the Indian economy also scaling Chinese levels of 37.5 per cent (from 27.1 per cent and 25.3 per cent during the preceding periods mentioned). The very fact of both the average GDP growth and capital formation rate slowing down in the 10 years after that, to 6 per cent and 31.3 per cent respectively, is indicative of Singh’s prime ministerial term coinciding with the “animal spirits” of Indian entrepreneurs truly being unleashed.

However, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s was a chequered economic record, unlike the reforms as Finance Minister for which he would, perhaps, be more remembered. The nineties and noughties were a time of hyperglobalisation. As world trade and capital flows boomed – albeit with brief interruptions like the 1997 Asian currency crisis and the 2008 world financial meltdown – it enabled India’s low-cost manufacturing and abundant technical manpower to be leveraged for integration into global value chains. The rising tide then lifted all boats, including India’s. But the Singh-led government also presided over the building up of macroeconomic imbalances, manifested in both “twin deficits” and “twin balance sheet” problems. The twin deficits – on the fiscal (government finances) and external current account (balance of payments) fronts – is something he would have loathed as an economist who completed his Tripos at Cambridge and DPhil at Oxford. The twin balance sheet crisis was a product of the same “animal spirits”, leading to overinvestment and overborrowing by private corporates, on the one side, and banks freely lending without evaluating the capacity for projects to generate cash flows to service debt, on the other. The end result was “animal spirits” working in the reverse, with an extended period of risk aversion by overleveraged corporates and bad loans-saddled banks alike. The effects of a growth slowdown and drying-up of investments is something that the succeeding Narendra Modi-led government has had to deal with for much of its ongoing tenure.

harish.damodaran@expressindia.com

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package