Prathiksha Ullal

Feb 24, 2025 12:58 IST First published on: Feb 24, 2025 at 12:58 IST

Sociologist Max Weber correlated the very idea of “work is worship” to the starting point of the spirit of capitalism. This meant that salvation was linked to day in and day out of hard work. However, in the 21st century, with renewed pressures and stressors of modern life, the Indian youth and their relationship with work have considerably changed and are presently rock-strewn at best. This raises many questions around the very nature of upskilling in engineering educational institutions and the prevailing sense of job insecurity in the IT sector. They assume renewed importance in the light of the recent layoffs of over 350 freshers by tech giant Infosys. In the run-up to the grand visions of Viksit Bharat, these layoffs constitute a worrying trend.

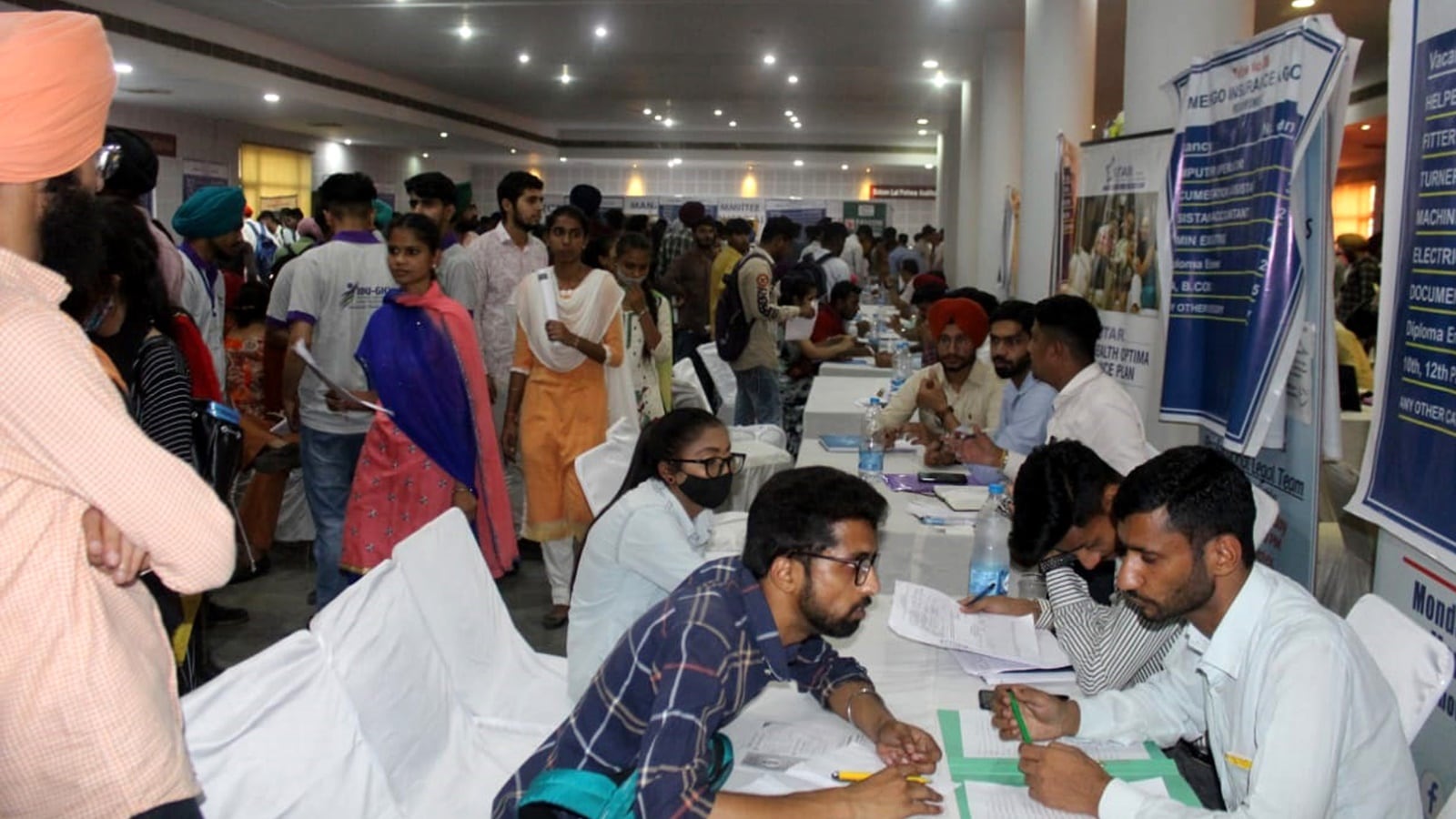

India, one of the youngest nations in the world, is poised on the verge of a once-in-a-lifetime demographic dividend opportunity with 26 per cent of the population in the age group of 10-24 years. Against this backdrop, we need to recall the Economic Survey of 2023-24 that highlighted the need for the Indian economy to generate over 78.5 lakh non-farm jobs annually until 2030 to productively engage its growing working population. This is one of the foundational steps for India’s journey to become a developed country by its 100th anniversary of Independence.

Story continues below this ad

Job creation ought to be of pivotal importance to achieve sustained economic growth, but that cannot be our sole focus. It is time to re-conceptualise the idea of reform in employability. The success of employability ought to be judged on the twin qualifiers of entry into the job market and retention. Firstly, instituting structural changes ought to begin with reforming university education. Apart from some updates in the syllabus of computer engineering courses, the syllabi of other branches of engineering such as mechanical, civil and electrical engineering have not gone through any considerable update in the last three to four decades. This creates a widening gap between the engineering academia and the industrial requirements of tech giants. This gap can be sufficiently filled by first updating the curriculum with the latest technological advancements and second, by incorporating practical and appropriate skill development programmes in line with industrial standards in the final year of these engineering courses.

These structural reforms can bring about considerable improvements in the employability of Indian youth by adequately equipping them to enter the job market and subsequently increase the chances of their retention, with additional training obtained from their respective companies. The problem of employability is a systemic issue that cannot be solved in departmental silos. It requires an integrated approach between education and skills at the university education level.

One way to achieve this would be for universities to mandatorily collaborate with skill development agencies to equip students with industrial requirements during the final year of engineering course structures. This would bring in a convergent approach to skill development which is now conceptualised largely as a post-educational endeavour. In the post-industrial modern era, this is an existential requirement. After all, to be skilled is to be.

Story continues below this ad

The writer is a research fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy