On Friday, a Delhi court ordered the framing of charges against Congress leader Jagdish Tytler for allegedly inciting a mob attack on a gurdwara that killed three men during the anti-Sikh violence in the national capital in 1984. On Friday, too, the high priests of the Akal Takht in Amritsar, the seat of supreme Sikh religious and temporal authority, declared Sukhbir Badal, president of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), as “tankhaiya” — that is, held him guilty of religious misconduct — for “mistakes” he made, and decisions he took, as deputy chief minister and party chief, 2007 to 2017.

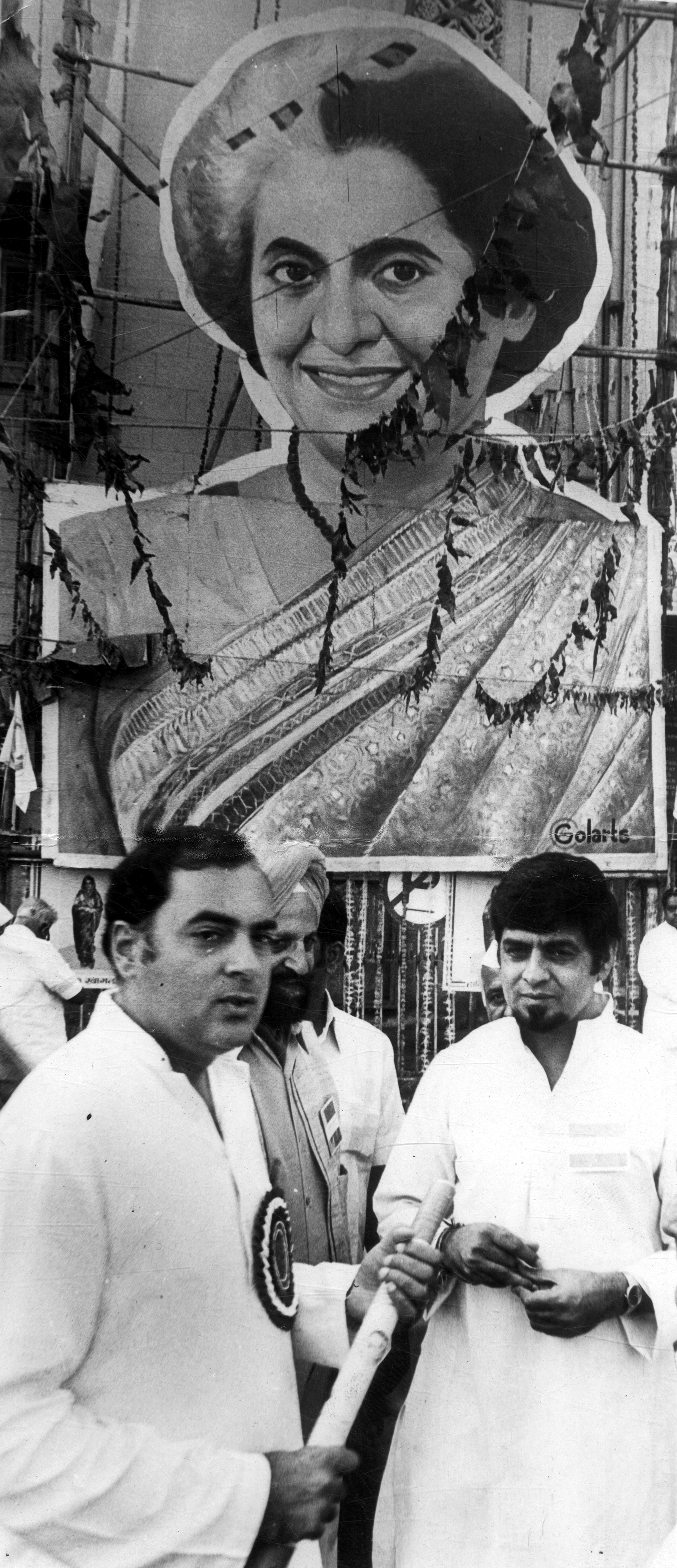

The first, the stunningly belated court order in a case related to the mass violence that targeted Sikhs in Delhi and beyond — the official toll was 2,733 in Delhi alone — when mobs took over the streets after the assassination of a prime minister and the Congress-ruled state was complicit or looked on, points to a searing saga of justice delayed and denied. Four decades later, justice is still buried deep under layers of impunity.

The second, the spectacle, perhaps a pantomime, of the punishment of SAD’s top-most leader by an authority appointed by the SGPC, the apex body of the Sikhs in which the SAD has a majority — elections to the SGPC were last held in 2011 when the SAD was still ruling the state — is the most recent reminder of a political vacuum that stretches on.

There is speculation that Sukhbir Badal’s “punishment” is a ploy to help him “cleanse” himself by mounting a public “atonement” — that it is a recognition by the SAD that desperate measures are needed to shake off accusations that trail the party. These are — that its government failed to bring the guilty to book in incidents of desecration of Guru Granth Sahib in 2015, that it promoted police officers shadowed by their role in the decade Punjab lost to militancy, and that it made backroom deals with the controversial and politically influential Dera Sacha Sauda. Whatever the truth of the accusations, the SAD, for long a dominant force in Punjab and one of India’s oldest regional parties, is evidently in free fall, its electoral tally plunging to a meagre 3 MLAs and 1 MP.

Punjab, then, is the home ground of both the crises flagged by events this week, in Delhi and in Amritsar — an elusive justice, and a lack of political leadership that can win the people’s trust and help the state move on from a past that continues to haunt it.

These crises were also a part of the simmering discontents that bubbled to the surface in the farmers’ movement that roiled the state and reached Delhi’s doorstep in 2020.

That movement showcased the widespread cynicism about politics that had taken hold in Punjab. It kept its platforms determinedly non-political, pushing aside all established politicians and parties. Its forcefulness finally led to the roll-back in November 2021 of the three farm laws that had been pushed through by the Narendra Modi-led Centre, without consultation.

A few months later, however, when the AAP swept the assembly election, its large victory promised a return of politics to the steering wheel, and for the state, a new beginning. That was not to be.

By all accounts, the AAP is fumbling and flailing in a state it conquered two years ago. Even after making the bi-polar contest a triangular one in Punjab, Arvind Kejriwal’s party remains divided between Chandigarh and Delhi, and hobbled by its own lack of organisation and long-term thinking. The results of the 2024 general election have pointed to a growing disillusion in the state — of its 13 seats, the ruling AAP won only 3, the SAD-in-decline got 1, and the faction-ridden Congress won 9 by default. All three players have been served a warning by the independent candidates who won the remaining two seats.

Amritpal Singh, a proponent of Khalistan, won from jail in Khadoor Sahib, and the Faridkot seat went to Sarabjeet Singh, son of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassin Beant Singh. Their victories may be a vote for what they are seen to stand for, or a vote against the alternatives offered by mainstream parties — either way, there is reason to worry.

Farmers are back at the Shambhu border, protesting for a legal guarantee for MSPs, even as the state’s other crises also billow unchecked — from the lack of diversification within agriculture and the economy, to the unemployment and drug-addiction problems that are driving away the young to foreign countries.

Be it the slow crawl of justice, then, or the travails of the powerful politician brought to his knees— they are telling glimpses of a once-proud state in search of a closure that eludes, and a resolution that is still missing.

Till next week,

Vandita