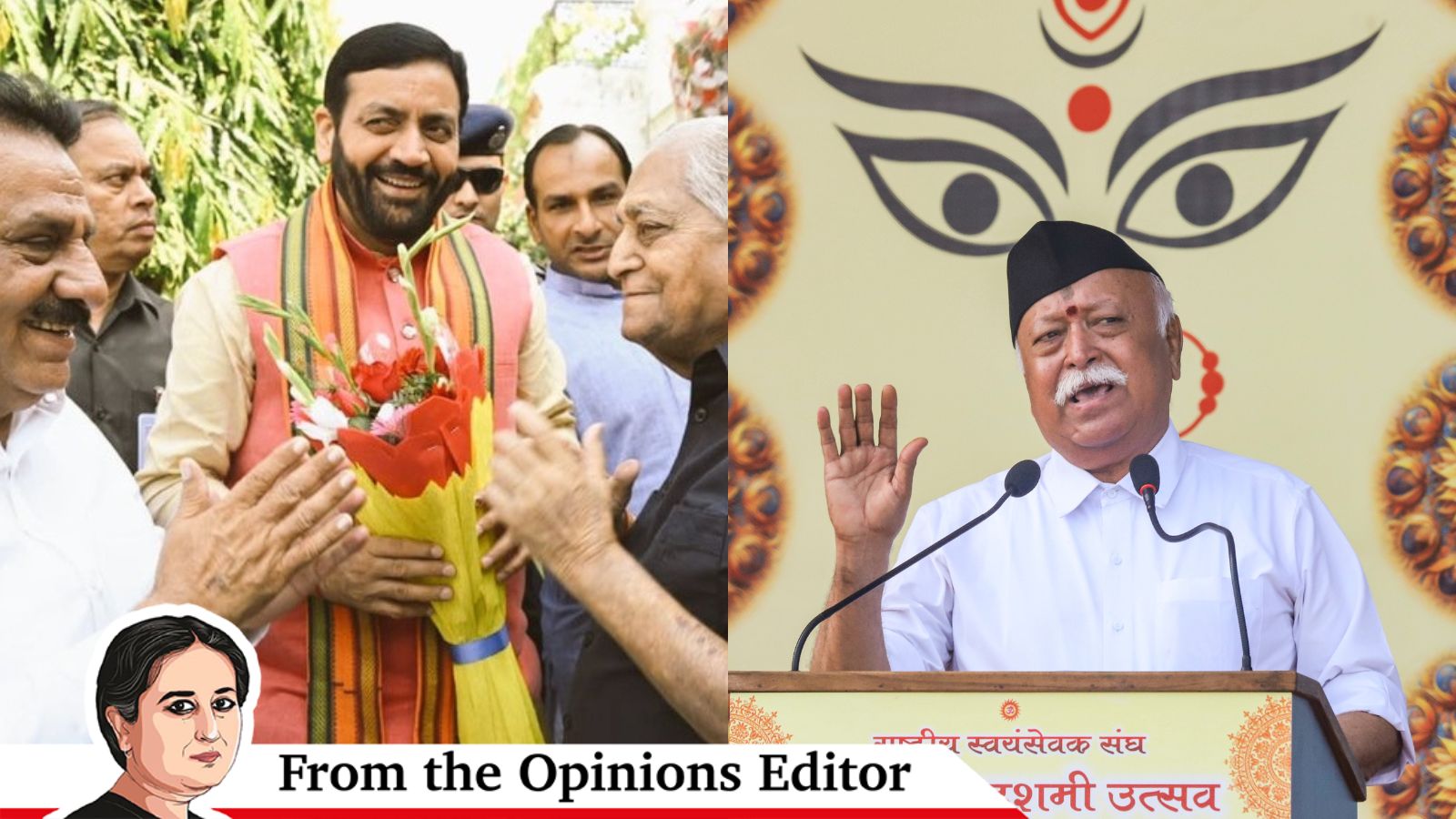

The week started with the Haryana and Jammu and Kashmir election results, and the first outcome upended all predictions. It ended with RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s call in his annual Dussehra address at Nagpur, for going back to Sangh basics.

The Haryana results were surprising, most of all, because they upset the dominant narratives that had preceded them, which had built upon the Lok Sabha scoreboard a few months earlier. The Congress, seen to be resurgent since the June result, was widely expected to wrest the state from the ruling BJP that was not only battling anti-incumbency, but was also being perceived as a party whose fortunes had, going by its failure to win a majority at the Centre, begun to inexorably dip.

In the end, the BJP’s return to power in Haryana, despite the Congress vote share going up by 11 per cent, said at least two things — one, the seat-vote dissonance, a long-standing feature of the first-past-the-post electoral system, that had worked to the advantage of the Congress in the general election, favoured the BJP in Haryana. And two, BJP victory and Congress defeat looked big and dramatic not against each other — the two parties are separated by less than 1 per cent vote share — but when juxtaposed with the expectations of pollsters and pundits.

The election outcome in Haryana is a reminder, most of all, that political reality in a large and diverse country does not follow the all-or-nothing/winner-takes-all logic that shapes the viewfinder of political observers and analysts in a hurry. It compels us to consider how, on the ground, both electoral victory and defeat are more tenuous and more incomplete than they seem, and why both need to be seen as part of longer and layered processes.

In this spirit, in a recent paper, Milan Vaishnav and Caroline Mallory, at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, urge a second look at the conclusions and certitudes spawned by the Lok Sabha results. Does the 2024 verdict mark a return to the coalition era that the BJP’s decisive single-party majority in 2014, the first in three decades, had ended? Has the “fourth party system”, marked by BJP dominance, now been replaced by a “reversion to a more decentralised, fragmented era”?

The “party systems”, a framework developed by political scientist and Express columnist Yogendra Yadav, were three, before 2014 — the first, dominated by the Congress, from Independence till 1967, when Congress lost crucial states; the second, from 1967 to 1989, when Congress remained in control at the Centre even as it lost dominance nationally; and the third, from 1989 to 2014, when no single party was the primary or organising pole of national politics even as several forces were unleashed, lower castes gained political representation, political competition and federalisation increased, and coalition politics came Centre-stage. The 2014 election seemed to resurrect the one-party dominance system, with the BJP replacing Congress as the centre-piece.

Vaishnav and Mallory warn against a reading of the 2024 general election verdict that sees it as a clean break from the fourth party system, or its repudiation and reversal. The main attributes of the fourth party system, they say, remain mostly intact, despite the setback to the BJP. Because: “Although the BJP fell short of a parliamentary majority, it remains a system-defining party. By and large, parties contest elections in India in favour of, or in opposition to, the Modi-led BJP.”

They lay out evidence to make their case: BJP’s vote share in 2024 declined by less than 1 percentage point from 2019, with losses in the Hindi heartland but gains in eastern and southern India; Congress vote share in 2024 was lifted by its key allies and was still its third worst performance ever, worse than even its dip in the coalition period; the BJP has expanded its pan-India footprint, fielding candidates in 441 constituencies, a new record, and emerging as either the winner or runner-up in 393, an all-time high, while Congress fielded candidates in less than 400 seats for the first time since Independence, and was a top-two finisher in only 266; the BJP has expanded its footprint at state-level considerably, while the Congress continues to lag far behind in terms of the number of states it rules, and the number of state legislators in its kitty, which is also showcased in the relative strength in Rajya Sabha of the two parties.

In many ways, the fourth party system is with us still, along with the challenges posed by the BJP’s project of straitjacketing and homogenisation in an unequal and diverse country. Mohan Bhagwat’s annual Dussehra address was a reminder of this.

The RSS chief spoke at length about caste, and the immediate context made it look new and remarkable — the 2024 electoral setback to the BJP was seen to be in part because of the stoking of Dalit anxieties, and Rahul Gandhi has made the demand for a caste census his political theme. But Bhagwat’s address was essentially a reiteration of the old, and an underlining.

Bhagwat painted a picture of a nation on the move, but also, and forever, under siege. The threat, in his telling, comes from external forces envious of India’s rise, and also from the enemies within — “deep state, wokeism, cultural Marxism”. He spoke of the pressing need for the “Hindu samaj” to be organised or “sangathit”, “sashakt”, powerful, and united.

It was in this context that he spoke of the need for outreach to lower castes, and for there to be “samajik samrasta” or social harmony. For the RSS — which established the Samajik Samrasta Manch way back in 1983 to reach out to subaltern groups — the focus has always been, and it continues to be, on harmony and tolerance in service of Hindu unity, not on ideas and ideals of backward caste empowerment and social justice.

Till next week,

Vandita