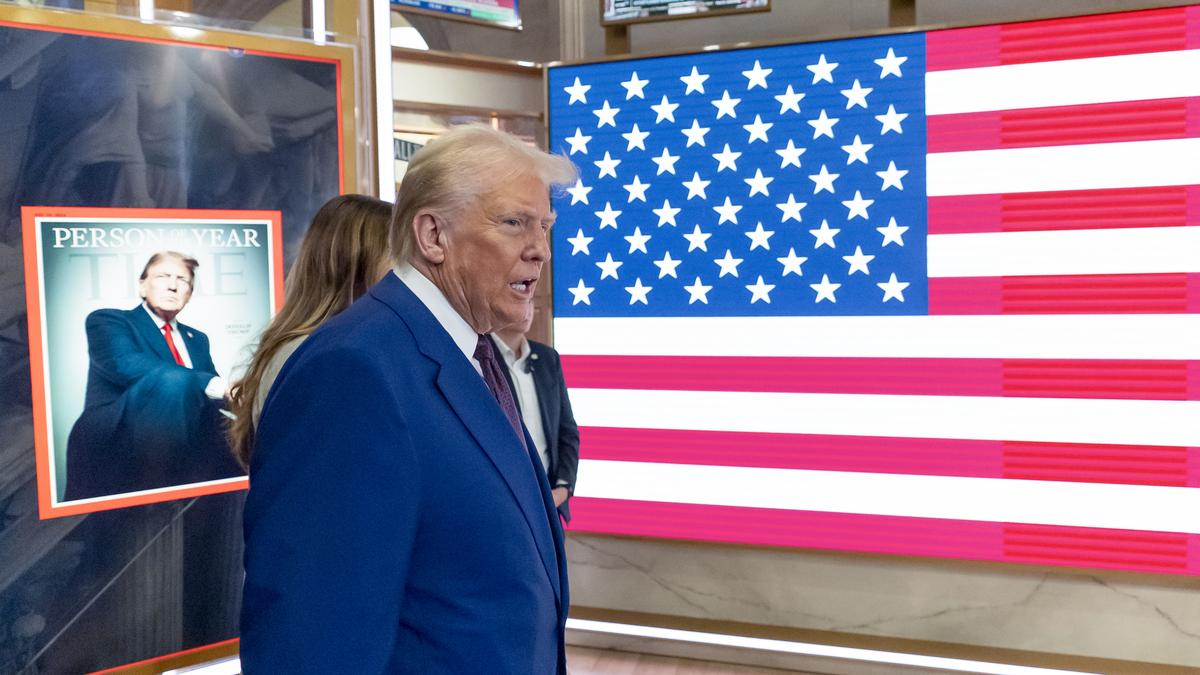

‘As the world braces for Trump 2.0, South Asia will not be immune to the broader structural shifts’ | Photo Credit: AP

In January 2025, Donald Trump will be sworn-in as the 47th President of the United States of America. Mr. Trump’s re-election, and subsequent return to office, have triggered curiosity and “nervousness” in many countries. However, in South Asia, he is likely to offer a distinct continuity. His ideology and foreign policy goals will continue to push for increased cooperation, collaboration, and consultation with India in South Asia even as his leadership style, decision-making nature, and management of great power politics will provide new opportunities and challenges.

Factors in U.S.-India ties

India and the United States have enjoyed an upward trajectory in their relationship since the beginning of the millennium. Acknowledging its leadership in the region, the U.S. even labelled India as a net-security provider in 2009. The Biden administration (2021-24) has emulated a similar outlook. With China’s increasing aggressiveness and assertiveness, India and the U.S. have strengthened their engagements and cooperation in South Asia. Through its Indo-Pacific strategy, the U.S. wants to supplement India’s regional leadership to counter China and maintain the values-based order. Its cooperation with India on the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) projects in Nepal and helping Sri Lanka out of its economic crisis, indicate this growing cooperation. Besides, Mr. Biden’s passive relations with Pakistan after withdrawing from Afghanistan helped India and the U.S. foster a mutual vision for the region.

The relationship has not been free of dissonance and divergences. New Delhi’s primary objective of cooperating with the U.S. is to push back against China and offer alternative development partnerships. However, the Biden administration has selectively scrutinised some countries on democracy and human rights under the pretext of upholding a values-based order and pushing back China. While India supported the Sheikh Hasina government in Bangladesh and pragmatically engaged with Myanmar’s junta, the U.S. pressured both regimes, including imposing targeted sanctions. This pressure nudged them closer to China. Similarly, sanctioning Indian firms for collaborating with Russia and accusations of corruption against the Adani Group has faltered two Indian projects in Sri Lanka, leaving India to face the brunt and consequences of the decisions.

There could be less irritants

However, Mr. Trump’s return is likely to assuage these irritants. As in his first term, Mr. Trump has continued to hint at burden sharing, reciprocity, nationalism, and competing against China in his foreign policy. If Mr. Trump walks the talk, he will prioritise pushing back against China while giving less importance to human rights, democracy, and nation-building. He would also want India to take the lead in the region while the U.S. would supplement the same. This would leave less space for divergences and enhance collaborative policies between both countries. Another potential irritant between both countries was concerning their policies on Afghanistan and Pakistan. During his first term, Mr. Trump punished and cooperated with Pakistan and urged India to take an active role in finding a sustainable solution in Afghanistan. With the U.S.’s withdrawal from Afghanistan and Pakistan’s little strategic importance, this issue is of little dissonance now.

During his first term, Mr. Trump promoted capacity building, development assistance, defence agreements, and cooperation with the South Asian countries. This nature of assistance would continue, given his ambitions to counter China and supplement India. Mr. Trump’s little focus on democracy, nation-building, and human rights (like in his first term) would also benefit Sri Lanka, where a new government is still looking for economic assistance and exploring a lasting solution to the Tamil issue.

This approach could benefit Myanmar and the Taliban too, although it is unclear to what extent Washington would like to engage them. However, Bangladesh, which is undergoing a political transition under the new regime, will face challenges and a potential reduction in assistance.

China and the region

Mr. Trump’s confrontational approach to China will also put South Asian countries under more pressure. Given his erratic decisions, Washington will likely be less tolerant of South Asian countries’ agency and consistent playing of one great power against the other. Besides, the region’s consistent politicisation and ambiguity over investments, defence cooperation, and agreements will likely invite more pressure from the U.S. to seek reciprocity. However, his promise of bringing peace between Russia and Ukraine and resolving the crisis in West Asia (if successful) will help weakened South Asian economies to overcome their food and fuel inflationary pressures.

As the world braces for Trump 2.0, South Asia will not be immune to the broader structural shifts. Yet, the region is likely to see more continuity. With India and the U.S. likely to increase their cooperation in South Asia and bridge their divergences, Mr. Trump’s ideology, leadership style, and management of great power politics will have opportunities and challenges for the region. How South Asian countries will cope with the new administration, even as they balance China and India, is yet to be seen.

Harsh V. Pant is Vice-President for Studies and Foreign Policy at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF). Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy is an Associate Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Observer Research Foundation

Published – December 14, 2024 12:08 am IST