News of a yet another ghastly rape and murder, this time of a 31-year-old doctor at the government-run RG Kar Medical College and Hospital in Kolkata has led to massive protests, a nationwide strike by doctors, the trading of charges between ruling party TMC, Congress and the BJP, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi making an unprecedented Independence Day demand for harsh penalties, including death, as a deterrent against such “demonic acts”.

“It’s good that there is so much public uproar and everyone is actively engaging in the discussion,” says Amrita Dasgupta of Swayam, a feminist organisation with 29 years of experience in dealing with gender inequality and violence against women and girls. “But there is a larger problem that goes beyond just one crime. We as a society need to address it because it impacts us all.”

Following the public protests in the aftermath of the December 2012 gang-rape and murder, the then UPA-led government enacted India’s toughest laws on rape. Jail time was enhanced; the death sentence brought in certain cases; the definition of rape itself expanded, and offences such as stalking recognised as separate crimes.

Nearly 12 years later, the data paints a grim picture. The National Crime Records Bureau reports 31,516 rapes in 2021, 86 a day, a 20% increase over the previous year.

The problem is that we look at cases of rape as single, disparate instances when in fact they are part of a far wider problem of violence against women and girls, continues Dasgupta, where one in three women worldwide are subjected to violence and most women don’t even report it. Stereotypes of masculinity continue to play out on film, in ads, on social media. “Boys are not born violent but there is a socialisation process that allows boys and men to behave in a certain way,” she says.

Rape culture, is “a social environment that allows sexual violence to be normalised and justified, fueled by persistent gender inequalities and attitudes,” defines UN Women.

To break the cycle we need to address it.

Stop focusing on the victim

By now we know, or ought to, that age, economic status, geography, caste, occupation, skin colour and sexual orientation of the victim is irrelevant. Babies get raped and so do grannies. Women in bikinis get raped and so do those in burqas. It does not help to ask what she was wearing or why she was out so late.

Mamata Banerjee who is now asking, bizarrely, for the culprit(s) in this case to be hanged by month’s end, perhaps has forgotten dismissing the 2012 Park Street rape as a “staged incident” where her own party’s MP suggested that the crime was not a rape as much as a “deal” that had gone wrong.

The Park Street victim refused to be shamed. She insisted on using her name, Suzette Jordan, pointing out that she had done nothing wrong. She might not have been eviscerated, she told me in an interview back then, but her trauma of being raped was real.

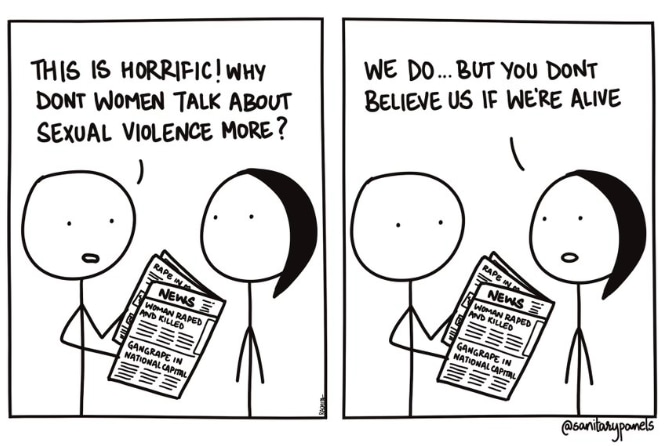

Earlier this week, Wrestling Federation of India’s new head, Sanjay Singh, widely regarded as a proxy for Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh who was forced to step down following charges of sexual abuse, took a sly dig by saying the country could have won six more medals if the wrestlers hadn’t protested. His statement is the answer to the question on why women don’t speak up. In fact, Vinesh Phogat who did, along with other wrestlers, remains a champion, medal or not, for having the courage to speak up for young women wrestlers across the country.

Rape happens because men rape. Yet hostels routinely lock up women at night for “their own safety”? Earlier this week, a medical college in Silchar asked women doctors and students to stay indoors at night. In the face of outrage, it hastily withdrew its advisory. Perhaps next time they might want to try locking up the men instead.

Making justice work

Of the seven women who wanted justice for being raped during the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, one died in childbirth and the other five just gave up, some under pressure from the accused men, others from their own families. Only one woman persisted and still it took nine years, three Supreme Court interventions, the tireless efforts of her pro bono lawyer, Vrinda Grover and her own boundless courage to finally get a conviction in May 2023.

Of the seven women who wanted justice for being raped during the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots, one died in childbirth and the other five just gave up, some under pressure from the accused men, others from their own families. Only one woman persisted and still it took nine years, three Supreme Court interventions, the tireless efforts of her pro bono lawyer, Vrinda Grover and her own boundless courage to finally get a conviction in May 2023.

In the 2002 post Godhra riots, 14 people, including the three-year-old daughter of Bilkis Bano were killed. Bilkis herself, five-and-a-half-months pregnant managed to survive a gang-rape. When the first information report (FIR) was filed the next day, the gang-rape was left out and so were the names of the men. A year later when not a single arrest was made, Bilkis approached the Supreme Court. It took another a year for the CBI to file a chargesheet. The court ordered the trial to be moved out of Gujarat to Mumbai.

Six years after the riots, a special court convicted 11 men and sentenced them to life imprisonment. The sentence was upheld by the Bombay high court in 2017. Then on Independence Day in 2022, the men were granted remission and walked out of jail amidst garlands and ladoos. It took another Supreme Court order to send them back in jail.

Why are victims paying such a high price for justice? When the accused offender is a VIP with political connections, whether it’s Kuldeep Singh Senger or a Chinmayananda, a Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh or Ram Rahim, witnesses will turn hostile, their family members will lose jobs or even their lives, victims will be attacked and set ablaze while on their way to provide testimony. Despite the odds, even when they are convicted, parole and furlough is generously made available, making a mockery of tough sentences. Ram Rahim is out on his eighth furlough in three years. There are no calls for strikes or protests over this.

The criminal justice system is failing even child victims, says Audrey D’Mello, programme director, Majlis. For instance, she says, in child sexual assault, police file FIRs with alacrity if there is penetrative assault, but in cases of touching or harassment, less than 5% cases are filed.

On paper, police stations are supposed to have a special child friendly room, but these are often used for storage and, so, while a child is testifying, other police personnel will flit in and out. “You can have any number of child friendly and victim friendly measures on paper, but from the moment a child enters the police station, they are treated as the accused. Police will look at the age, extent of injury and family support. If these are missing, they will have no interest in recording a case,” says D’Mello who is in the process of finalising her report on the implementation of the POCSO Act in Maharashtra.

Standard operating procedures that exist on paper must be implemented. Gender sensitisation of police, lawyers, public prosecutors and judges must be ongoing. We need to see more women hired at every level, from prosecutor to judge.

End selective rage

How is it that the “conscience of the nation” is shaken by some rapes and not others? We will march for the doctor and the physiotherapy student (2012) but not the child in the slum or the Dalit girl in Unnao and Hathras. As for the eight-year-old in Kathua, let it be our enduring shame that lawyers actually marched in favour of the rapists and her killers.

Meanwhile, in Mumbai, Powai, residents at Hiranandani Gardens decided to hold a protest for the doctor. When residents from Jai Bhim Nagar, a nearby settlement with 700 families, wanted to join, they were denied permission, tweeted Nikita Sonavane, co-founder of the CPA Project that focuses on challenging the criminalisation of oppressed caste communities. The exclusion of the women from Jai Bhim Nagar is “one of the many stories of vacuous ‘solidarity’ that sees the inclusion of Bahujan women as disrupting ‘collective struggles’ of women,” she writes.

If your rage is dependent on who is raped, the circumstances of the rape, the extent of injuries, which political party is in power, then you are a part of the problem.

Zero tolerance

It might begin with a stalking or perhaps a slap to a sister for some minor transgression. It might move on to groping women in a crowded bus or showing pornography to a subordinate woman at the workplace.

I would be very surprised to learn that rape is the first crime of violence against women committed by a man. Somewhere, he’s learned that society accepts violence. In states like Telangana, 83.8% of women interviewed by the National Family Health Survey-5 said domestic violence is justified under certain circumstances—a poorly cooked meal or speaking rudely to in-laws, for instance.

This past week, a video of a man in Rajasthan dragging his wife who was tied to his motorcycle went viral. The wife has not filed a complaint, but the police have taken suo motu cognisance and the man has been arrested.

I wondered how it is that someone took the time to take the video, but nobody intervened to stop the man.

Media, play your part

Your readers do not need to know the graphic details of an autopsy report—how many injuries, where, and the condition of her body when it was found. The only thing your voyeuristic account accomplishes is to further desensitize an already numb society to violence against women. Please stop.

And, yes, the law prohibits the publishing of victims’ names, particularly if they are minors. But a rape victim who ends up dead did not ask to be martyred, so please refrain from inane epithets like Nirbhaya, Damini etc that dehumanise flesh and blood women with real dreams and aspirations. Use December 2012 gang-rape, Kathua, Shakti Mills, Hathras. Provide readers with context and they will know who you are talking about.

Use words judiciously. What the hell is eve-teasing? Call it street sexual harassment.

Finally, even outside the context of sexual violence, a word to the male interviewer who this week asked shooter Manu Bhaker, the only Indian wrestler with two bronze medals in a single Olympics, about her ‘beauty’. Please stop judging women by the way they look and by the beauty standards you set up for them. By doing that, you are undermining their talent, accomplishment and worth as contributing citizens.

Ensure safety

It is the job of workplaces whether it’s a factory or a government hospital to provide all employees with a safe working environment. If a woman is attacked or raped within these premises, then the blame and criminal culpability must lie squarely with employers.

Not just CCTVs, is your workplace compliant with the law on protection from workplace sexual harassment? Bonus points if it holds regular gender sensitisation workshops and programmes. More bonus points if DEI (diversity, equality, inclusion) is a genuine aim rather than a catchy tag to make your social media look better.

Challenging ideas of masculinity

When Breakthrough, an organisation that works to end violence against women, began working with adolescent boys in Uttar Pradesh on gender stereotypes, a strange thing happened. The boys went back home and started helping their mothers with housework. They increasingly took a stand against violence against women.

The change during the five-year intervention was measurable and proved that changing long held social norms is possible. All that is needed is the will.

Schools everywhere now talk of “good touch/bad touch”. More is needed. Textbooks must be examined with gender stereotypes excised. Gender sensitisation with concepts like consent must be part of the curriculum

Change is possible only if there is a will.

Read also: Young doctors battle apathy in the line of duty.

The following article is an excerpt from this week’s HT Mind the Gap. Subscribe here.