ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published. This story was reported in partnership with CBS News.

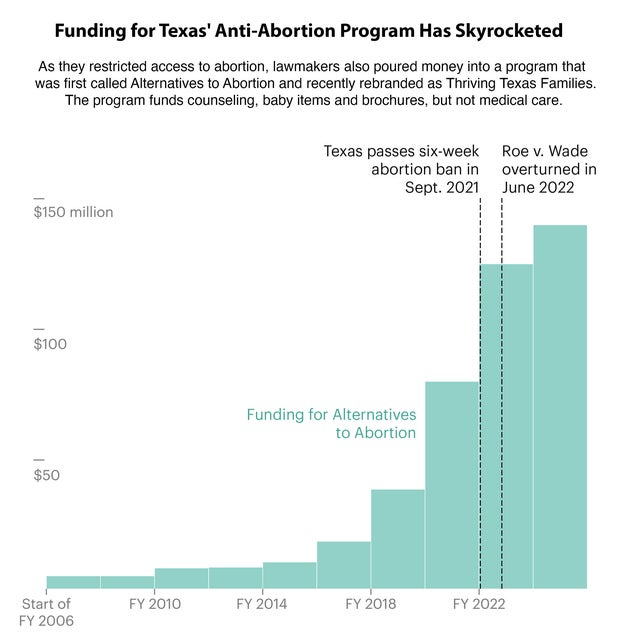

Year after year, while Roe v. Wade was the law of the land, Texas legislators passed measures limiting access to abortion — who could have one, how and where. And with the same cadence, they added millions of dollars to a program designed to discourage people from terminating pregnancies.

Their budget infusions for the Alternatives to Abortion program grew with almost every legislative session — first gradually, then dramatically — from $5 million starting in 2005 to $140 million after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the right to an abortion.

Now that abortion is largely illegal in Texas, lawmakers say they have shifted the purpose of the program, and its millions of dollars, to supporting families affected by the state’s ban.

In the words of Rep. Jeff Leach, a Republican from Plano, the goal is to “provide the full support and resources of the state government … to come alongside of these thousands of women and their families who might find themselves with unexpected, unplanned pregnancies.”

But an investigation by ProPublica and CBS News found that the system that funnels a growing pot of state money to anti-abortion nonprofits has few safeguards and is riddled with waste.

Officials with the Health and Human Services Commission, which oversees the program, don’t know the specifics of how tens of millions of taxpayer dollars are being spent or whether that money is addressing families’ needs.

In some cases, taxpayers are paying these groups to distribute goods they obtained for free, allowing anti-abortion centers — which are often called “crisis pregnancy centers” and may be set up to look like clinics that perform abortions — to bill $14 to hand out a couple of donated diapers.

Distributing a single pamphlet can net the same $14 fee. The state has paid the charities millions to distribute such “educational materials” about topics including parenting and adoption; it can’t say exactly how many millions because it doesn’t collect data on the goods it’s paying for. State officials declined to provide examples of the materials by publication time, and reporters who visited pregnancy centers were turned away.

For years, Texas officials have failed to ensure spending is proper or productive.

They didn’t conduct an audit of the program in the wake of revelations in 2021 that a subcontractor had used taxpayer funds to operate a smoke shop and to buy land for hemp production.

They ramped up funding to the program in 2022 even after some contractors failed to meet their few targets for success.

After a legislative mandate passed in 2023, lawmakers ordered the commission to set up a system to measure the performance and impact of the program.

One year later, Health and Human Services says it’s “working to implement the provisions of the law.” Agency spokespeople answered some questions but declined interview requests. They said their main contractor, Texas Pregnancy Care Network, was responsible for most program oversight.

The nonprofit network receives the most funding of the program’s four contractors and oversees dozens of crisis pregnancy centers, faith-based groups and other charities that serve as subcontractors.

The network’s executive director, Nicole Neeley, said those subcontractors have broad freedom over how they spend revenue from the state. For example, they can save it or use it for building renovations.

Pregnancy Center of the Coastal Bend in Corpus Christi, for instance, built up a $1.6 million surplus from 2020 to 2022. Executive Director Jana Pinson said two years ago that she plans to use state funds to build a new facility. She did not respond to requests for comment. A ProPublica reporter visited the waterfront plot where that facility was planned and found an empty lot.

Because subcontractors are paid set fees for their services, Neeley said, “what they do with the dollars in their bank accounts is not connected” to the Thriving Texas Families program. “It is no longer taxpayer money.”

The state said those funds are, in fact, taxpayer money. “HHSC takes stewardship of taxpayer dollars, appropriated by the Legislature, very seriously by ensuring they are used for their intended purpose,” a spokesperson said.

None of that has caused lawmakers to stop the cash from flowing. In fact, last year they blocked requirements to ensure certain services were evidence-based.

Leach, one of the program’s most ardent supporters, said in an interview with ProPublica and CBS News that he would seek accountability “if taxpayer dollars aren’t being spent appropriately.” But he remained confident about the program, saying the state would keep investing in it. In fact, he said, “We’re going to double down.”

What’s more, lawmakers around the country are considering programs modeled on Alternatives to Abortion.

Last year, Tennessee lawmakers directed $20 million to fund crisis pregnancy centers and similar nonprofits. And Florida enacted a 6-week abortion ban while including in the same bill a $25 million allocation to support crisis pregnancy centers. John McNamara, a longtime leader of Texas Pregnancy Care Network, has been working to start similar networks in Kansas, Oklahoma and Iowa. He’s also reserved the name Louisiana Pregnancy Care Network.

And U.S. House Republicans are advocating for allowing federal dollars from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program — intended to help low-income families — to flow to pregnancy centers. In January, the House passed the legislation, and it is pending in the Senate. Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., castigated Democrats for voting against the bill.

“That’s taking away diapers, that’s taking away resources from families who are in need,” she said in an interview with CBS News after the vote.

But, as Texas shows, more funding doesn’t necessarily pay for more diapers, formula or other support for families.

* * *

Lawmakers rebranded Alternatives to Abortion as Thriving Texas Families in 2023. The program is supposed to promote pregnancies, encourage family formation and increase economic self-sufficiency.

The state pays four contractors to run the program. The largest, which gets about 80% of the state funding, is the anti-abortion group Texas Pregnancy Care Network.

Human Coalition, which gets about 16% of the state funding, said it uses the money to provide clients with material goods, counseling, referrals to government assistance and education. Austin LifeCare, which gets about 3% of the state funding, could not be reached for comment about this story. Longview Wellness Center in East Texas, which receives less than 1% of the funds, said the state routinely audits its expenses to ensure it’s operating within guidelines.

Texas Pregnancy Care Network manages dozens of subcontractors that provide counseling and parenting classes and that distribute material aid such as diapers and formula. Parents must take a class or undergo counseling before they can get those goods.

The state can be charged $14 each time one of these subcontractors distributes items from one of several categories, including food, clothing and educational materials. That means the distribution of a couple of educational pamphlets could net the same $14 fee as a much pricier pack of diapers.

A single visit by a client to a subcontractor can result in multiple charges stacking up. Centers are eligible to collect the fees regardless of how many items are distributed or how much they are worth. One April morning, a client at McAllen Pregnancy Center, near the Texas-Mexico border, received a bag with some diapers, a baby outfit, a baby blanket, a pack of wipes, a baby brush, a snack and two pamphlets. It was not clear how much the center invoiced for these items.

McAllen Pregnancy Center and other Texas Pregnancy Care Network subcontractors were paid more than $54 million from 2021 to 2023 for distributing these items, according to records.

How much of that was for handing out pamphlets? The state said it didn’t know; it doesn’t collect data on the quantities or types of items provided to clients or whether they are essential items like diapers or just pamphlets, making it impossible for the public to know how tax dollars were spent.

Neeley said in an email that educational materials like pamphlets only accounted for 12% of the money reimbursed in this category last year, or roughly $2.4 million out of $20 million. She did not respond to questions from ProPublica and CBS News about evidence that would corroborate that number.

The way subcontractors are paid, and what they’re allowed to do with that money, raised questions among charity experts consulted for this investigation.

In the nonprofit sector, using a fee-for-service payment model for material assistance is highly unusual, said Vincent Francisco, a professor at the University of Kansas who has worked as a nonprofit administrator, evaluator and consultant over the past three decades. It “can run fast and loose if you’re not careful,” he said.

Even if nonprofits distribute items they got for free or close to it, the state will still reimburse them. Take Viola’s House, a pregnancy center and maternity home in Dallas. Records show that it pays a nearby diaper bank an administrative fee of $1,590 for about 120,000 diapers annually — just over a penny apiece. Viola’s House can then bill the state $14 for distributing a pack of diapers that cost the center just over a quarter.

But before they can get those diapers, parents must take a class. The center can also bill the state $30 for each hour of class a client attends.

Rep. Donna Howard, a Democrat from Austin, said the program could be more efficient if the state funded the diaper banks directly. Last year, she proposed diverting 2% of Thriving Texas Families’ funding directly to diaper banks, but the proposal failed.

Records show that in fiscal year 2023, Viola’s House received more than $1 million from the state in reimbursements for material support and educational items plus another $1.7 million for classes. Executive Director Thana Hickman-Simmons said Viola’s House relies on funding from an array of sources and that just a small fraction of the diapers it distributes come from the diaper bank. She said the state money “could never cover everything that we do.”

In some cases, reimbursements have created a hefty cushion in the budgets of subcontractors. The state doesn’t require them to spend the taxpayer funds they get on needy families, and Texas Pregnancy Care Network said subcontractors can spend the money as they see fit, as long as they follow Internal Revenue Service rules for nonprofits.

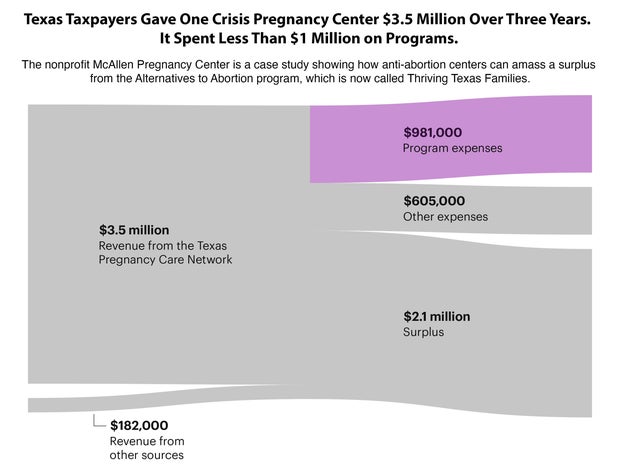

McAllen Pregnancy Center received $3.5 million in taxpayer money from Texas Pregnancy Care Network over three years, but it spent less than $1 million on program services, according to annual returns it filed with the IRS. Meanwhile, $2.1 million was added to the group’s assets, mostly in cash. Its executive director, Angie Arviso, asked a reporter who visited in person to submit questions in writing, but she never responded.

“This is a policy choice Texas has made,” said Samuel Brunson, associate dean for faculty research and development at the Loyola University Chicago School of Law, who researches and writes about the federal income tax and nonprofit organizations. “It has chosen to redistribute money from taxpayers to the reserve funds of private nonprofit organizations.”

Tax experts say that’s problematic. “Why would you give money to a recipient that is not spending it?” said Ge Bai, a professor of accounting and health policy at Johns Hopkins University.

The tax experts disagree with Texas Pregnancy Care Network’s argument that the money is no longer taxpayer dollars after its subcontractors are paid.

“It’s still the government buying something,” said Jason Coupet, associate professor of public management and policy at Georgia State University, who has studied efficiency in the public and nonprofit sectors. “If I were in the auditor’s office, that’s where I would start having questions.”

* * *

State legislators and regulators haven’t installed oversight protections in the program.

Three years ago, The Texas Tribune spotlighted the state’s refusal to track outcomes or seek insight into how subcontractors have spent taxpayer money.

Months later, Texas Pregnancy Care Network cut off funding to one of its biggest subcontractors after a San Antonio news outlet alleged the nonprofit had misspent money from the state.

KSAT-TV reported that the nonprofit, A New Life for a New Generation, had used Alternatives to Abortion funds for vacations and a motorcycle, and to fund a smoke shop business owned by the center’s president and CEO, Marquica Reed. It also spent $25,000 on land that was later registered by a member of Reed’s family to produce industrial hemp.

In an interview with ProPublica, a former case manager recalled how Reed would get angry if employees forgot to bill the state for a service provided to a client.

The former case manager, Bridgett Warren Campbell, said employees would buy diapers from the local Sam’s Club store, then take apart the packages. “We’d take the diapers out and give parents two to three diapers at a time, then she would bill TPCN,” said Campbell.

Reed declined to comment to a ProPublica reporter or to answer follow-up questions via email or text. Neeley, the Texas Pregnancy Care Network’s executive director, said the pregnancy center was removed from the program because its nonprofit status was in jeopardy, not because it had used money on personal spending. She said the network wasn’t responsible for monitoring how A New Life for a New Generation spent its dollars: “The power to investigate these matters of how nonprofits manage their own funds is reserved statutorily to the Texas Attorney General and the IRS.”

The Texas attorney general’s office would not say whether it has investigated the organization. Records show that after KSAT’s story, state officials referred the case to an inspector general and that the Texas Pregnancy Care Network submitted a report detailing how it monitored the subcontractor.

The state requires contractors to submit independent financial audits if they receive at least $750,000 in state money; Texas Pregnancy Care Network meets this threshold. However, its dozens of subcontractors don’t have to submit these audits — something experts in nonprofit practices said should be required. In the fiscal year before the alleged misspending came to light, A New Life for a New Generation received more than $1 million in reimbursements from the state, records show.

When ProPublica and CBS News asked how the Health and Human Services Commission detects fraud or misuse of taxpayer funds, Jennifer Ruffcorn, a commission spokesperson, said the agency “performs oversight through various methods, which may include fiscal, programmatic, and administrative monitoring, enhanced monitoring, desk reviews, financial reconciliations, on-site visits, and training and technical assistance.”

Through a spokesperson, Rob Ries, the deputy executive commissioner who oversees the program at Health and Human Services, declined to be interviewed.

The agency has never thoroughly evaluated the effectiveness of the program’s services in its nearly 20 years of existence.

It is supposed to make sure its contractors are meeting a few benchmarks: how many clients each one serves and how many they have referred to Medicaid and the Nurse-Family Partnership, a program that sends nurses to the homes of low-income first-time mothers and has been proven to reduce maternal deaths. The Nurse-Family Partnership does not receive Alternatives to Abortion funding.

In 2022, the Texas Pregnancy Care Network failed to meet two of three key benchmarks in its contract with the state: It didn’t serve enough clients and it didn’t refer enough of them to the nursing program. The state didn’t withhold or reduce its funding. McNamara disputed the first claim, saying the state changed its methodology for counting clients, and said the other benchmark was difficult to hit because too few clients qualified for the nursing program.

In May 2023, when lawmakers passed the bill rebranding the program, the state also ordered the agency to “identify indicators to measure the performance outcomes,” “require periodic reporting” and hire an outside party to conduct impact evaluations.

The agency declined to share details about its progress on those requirements except to say that it is soliciting for impact evaluation services. Records show the agency has requested bids.

Lawmakers decided last year against enacting requirements that would ensure certain services were evidence-based — proven by research to meet their goals — instead siding with an argument that they would be too onerous for smaller nonprofits.

Texas’ six-week abortion ban took effect in 2021, and more than 16,000 additional babies were born in the state the following year. Academics expect that trend to continue.

But the safety net for parents and babies is paper thin.

Texas has the lowest rate of insured women of reproductive age in the country and ranks above the national average for maternal deaths. It’s last in giving cash assistance to families living beneath the poverty line.

Mothers told reporters they are struggling to scrape together enough diapers and wipes to keep their babies clean. A San Antonio diaper bank has hundreds of families on its waitlist. Outside an Austin food pantry, lines snake around the block.

Howard, the Austin state representative, said ProPublica and CBS News’ findings show that the program needs more oversight. “It is unconscionable that a [Thriving Texas Families] provider would be allowed to keep millions in reserve when there is a tremendous need for more investment in access to health care services,” she said.

–Caroline Chen and Kavitha Surana contributed reporting.