India’s recurring tragedies which lead to countless lives lost and maimed, from road traffic accidents to monsoon flooding, have one common thread running through them: An incompetent state that is unable to enforce the laws. In addition, for some of these tragedies, there is a moral dimension that lurks just beneath the surface, and there is no better example of this than the recurrent calamities due to the consumption of illicit alcohol.

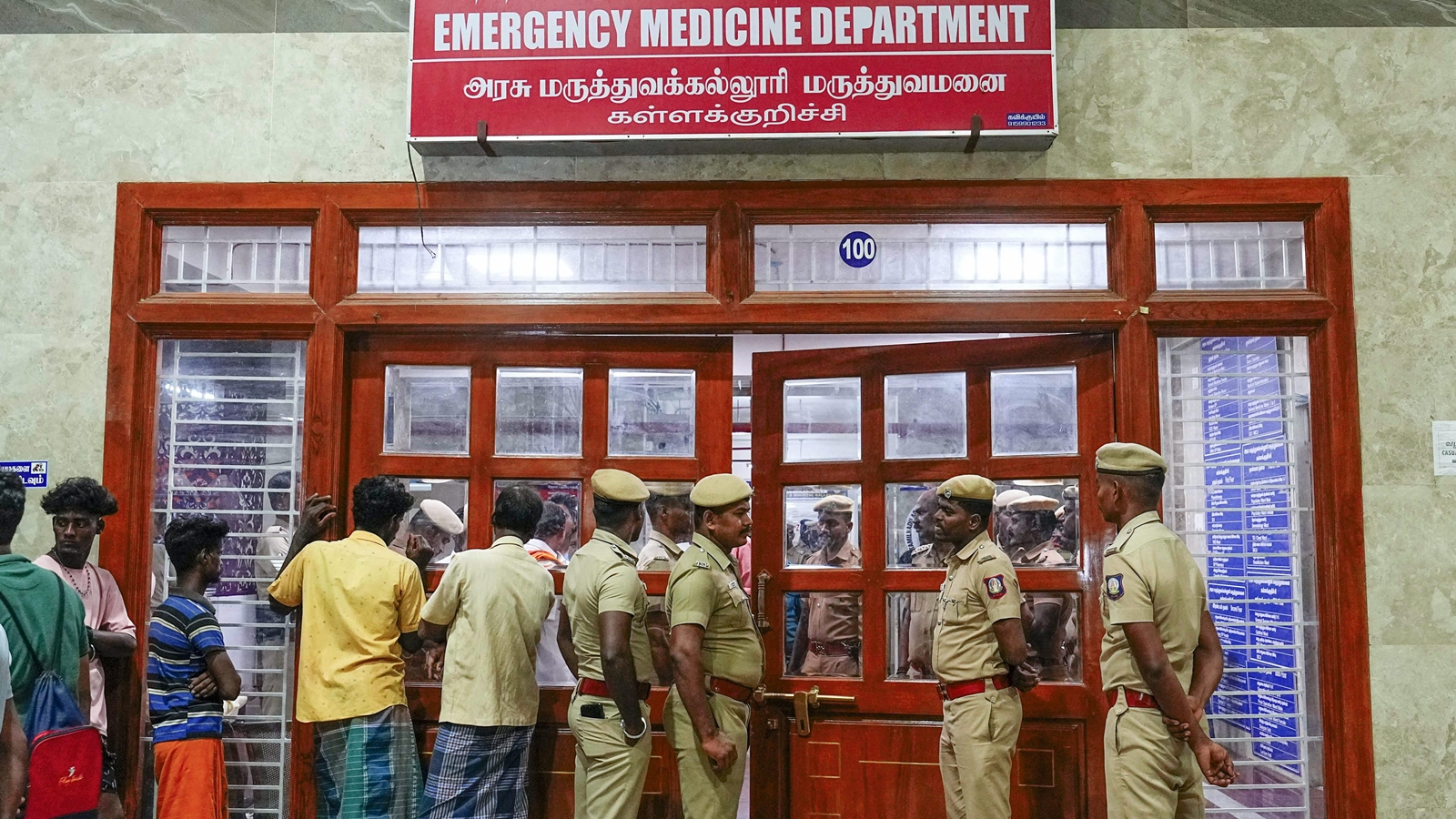

The most recent such occasion is only remarkable because of its sheer scale. Nearly 60 persons have died in the Kallakurichi hooch tragedy in Tamil Nadu. Alcohol consumption is associated with mortality in all countries, both due to its direct effects on various organs such as the liver and due to its indirect effects through impairing one’s abilities leading to accidents. But deaths due to poisoning by illicit alcohol are limited to a handful of countries, among which India ranks at the top. This is in large part due to the conflicting relationship the state has with the consumption of alcohol, oscillating between a sledge-hammer condemnation of drinking as a symbol of the decay of cultural values on the one hand, and an embracing of forward-looking modernity in which citizens are entitled to enjoy personal freedoms on the other.

This combination of contradictory positions is the result of the multi-hued history of alcohol consumption in India. References to alcohol use can be found in Vedic texts. There was widespread alcohol use even during the Mughal period, despite Quranic prohibition. The arrival of the British radically altered the dynamics of this laissez-faire situation as they strove to restrict the culturally sanctioned patterns of drinking, such as in community celebrations, which were closely tied to the consumption of indigenously produced alcoholic beverages. The colonial narrative was that such practices were primitive. They introduced the gin tonic and whiskey soda, conveniently distilled in industrial quantities and taxed generously under their watch, which spread from the secluded compounds of the British to the upper-class elites of brown sahibs.

Thus was born the uniquely Indian moniker of “Indian-made foreign liquor”, which became a symbol of colonisation designed to deplete Indians of their moral fibre. Abstinence and prohibition became a clarion call for the temperance movement that blended seamlessly with the Independence movement.

The first hints of prohibition were evident even before 1947. But it was only when our Constitution was ratified that India became the only secular and democratic country which required the state to implement prohibition of intoxicating substances, lumping alcohol with other drugs. As with all exhortations of moral purity, such values were heavily gendered with women being tarnished as being “loose” if they drank alcohol.

But, gin tonics and whiskey soda had already become an integral part of the social worlds of too many of India’s elite and governing classes. The actual realisation of the lofty ideals of abstinence was left to the individual states, of which only a handful, notably Gujarat, the birthplace of the Mahatma, imposed prohibition.

In the decades that followed, state policies have had to navigate the tightrope of not being perceived as licentious while also recognising that drinking is an integral part of society. Moreover, as Bihar’s experiment with prohibition demonstrated, alcohol became a potent electoral issue due to the pervasive experience of domestic violence fueled by alcohol while, as the ongoing crisis engulfing the AAP government in New Delhi demonstrates, the sale of alcohol was a major contributor to the exchequer.

Each state has evolved its own policy, somewhere on the spectrum from liberal to draconian. Some states have even evolved a hybrid approach to accommodate this contradictory stance. For example, Gujarat came up with a bizarre policy wherein residents were banned from drinking but out-of-state visitors could procure alcohol if armed with a doctor’s certificate stating that they had a drinking problem. More recently, the state allowed liquor in the ambitious GIFT City but only to permanent employees and their authorised visitors.

Such contradictory positions have led to the persistence of the illegal moonshine industry that thrives on the enormous profits which are to be generated to fulfil the desire of people to drink in contexts where the substance is criminalised, and where law enforcement agencies and the political class collude with the mafia or are simply incompetent to enforce the law. And, as with all such laws which limit personal freedoms, the poor suffer the most. In Bihar, prisons are bursting with poor men who were arrested for drinking. As everywhere in the country, most victims of hooch tragedies are the poor.

We need nothing short of a national consensus on finding the right balance in our approach to drinking alcohol. We can be guided both by public health science and the experiences of other countries. This might also offer an opportunity to revisit our policies on cannabis, another substance with a long and storied history of use in India. It was criminalised under pressure from the US while that country itself has become home to the largest legal cannabis industry in the world. Such policies would permit alcohol consumption and legalise, with strict quality controls, indigenous alcohol production.

At the same time, there would be zero-tolerance for alcohol-related offences, for example on bars for selling alcohol to underage drinkers — as has belatedly happened in the context of the notorious “Porsche” drink-driving deaths in Pune. The treatment of harmful drinking would need to evolve beyond the historic focus on in-patient deaddiction centres, a legacy of a morally grounded, disease-focused approach and offer evidence-based psychosocial interventions in a non-stigmatising way through the country’s primary care network.

I remember when I was a hospital resident in London back in the late 1980s when it was commonplace to drink heavily as pubs approached the mandatory closing hour of 11 pm, and then drive home inebriated. It required more than a decade of a combination of policies, from extending the closing hours of pubs to strict enforcement of drink-driving laws to lead to a culture change in British society such that it became socially unacceptable to drink and drive. It is time for us, as a nation, to engage in this journey.

The writer is Paul Farmer Professor of Global Health at Harvard Medical School

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 26-06-2024 at 14:32 IST