There’s a scene in the opening episode of Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar that speaks, to my mind, for Bhansali’s heroines: During a conversation over their ambitions, one of the protagonists, Lajjo, tells her foster sisters Bibbojaan and Alamzeb that the chasm between the dreams and destiny of Heeramandi’s courtesans are too deep to be breached. Bibbojaan, one of the few layered characters in the series, agrees: “Hum sone ke pinjre mein phadphadate hain aur khwab azadi ke dekhte hain (We live in gilded cages and dream of freedom)”.

Bhansali’s latest OTT offering, traces the lives of Lahore’s tawaifs in pre-Independence India. But you could take a sample of any of his movies — Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999), Devdas (2002), Saawariya (2007), Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela (2013), Bajirao Mastani (2015) or Padmaavat (2018) — and the impression that you are left with is of women who live in gilded cages, imagining freedom to look a certain way when it is only, after all, male gaze masquerading as female aspiration and agency. Consider this: In Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, it is not Aishwarya Rai’s Nandini who gets to make the choice of returning to Sameer. That decision is a largesse bestowed on her by her husband, Vanraj, placing a moral obligation on her. In Bajirao Mastani, Kashi, played by Priyanka Chopra, has to cope with the consequences of decisions men take for her — she has no say in Bajirao’s decision to marry Mastani, her refusal of conjugal rights to him is a result of his betrayal. In Saawariya, Rani Mukerji’s Gulab is a rebound option Raj (Ranbir Kapoor) turns to when the woman he is pursuing, Sakina (Sonam Kapoor), rejects him. In each of these movies, Bhansali’s imagination presupposes beauty and grandeur but the individuality he imbues his women with is inadequate, a prop for the men to play benefactors to women or for women to get into the skin of men.

One could argue that most of Bhansali’s directorial ventures are adaptations of works of literature — Saawariya is based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1848 short story White Nights; Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam on Maitreyi Devi’s Bengali novel Na Hanyate, Bajirao Mastani on Nagnath S Inamdar’s Marathi novel Rau — that his storylines are circumscribed by their plots and settings. But it fails to explain the unidimensionality of his women. Adaptations, as many of Bhansali’s colleagues have shown, can be liberating, offering a chance to look at old material in newer ways. Bhansali, however, clings to his outdated lens. His women are all objects of beauty and desire, operating in settings whose scale and grandeur could only belong to the realm of make-believe. Consequently, the women are removed from the real business of life by their distance from it. They are reduced to morality tropes — remove the names and Mastani could just as easily be Valour, Padmavati, Honour, Leela, Rebellion, and Sakina, Innocence.

Perhaps, a more problematic issue with Bhansali’s women is their interpretation of emancipation. Parochial wisdom would have us believe that it is easier for women to be best friends with diamonds than with each other; that there will always be a frisson of jealousy between two women, be it mothers-in-laws and daughters-in-law or female colleagues at the workplace. It’s easy too, to be deluded by this idea. After all, in our public discourse, female ministers routinely take personal swipes at colleagues from opposing parties; in the saas-bahu landscape of television dramas, women are often portrayed as their own worst enemies. Our films, even those that profess to champion women, like those made by Bhansali, internalise the language of misogyny, in which women must fight each other for love, money, fame or control. Worse still, that they must speak and operate in the same patriarchal currency that framed the narratives of their lives. It might take shrewd business sense to run a business in Heeramandi but does Mallikajaan or Rehana need to be the one-tone ruthless huzoor to keep control? In Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela, a reimagination of Romeo and Juliet, Leela’s mother Dhankor Baa (Supriya Pathak Kapur) is a precursor to Mallikajaan’s heartlessness, relying on violence to retain her hold over her community. Can there only be room for one obsessive pursuit at a time — professional supremacy, honour, love returned or unrequited — with no room for compassion or companionship, curiosity or second thoughts?

A reimagination of agency in a cinematic universe could mean taking the same source material and showing what happens when the good isn’t flawless and the bad not completely without redeeming qualities. It could mean showing women trying to make spaces for each other that weren’t there for them in their moments of strife. If nothing, it could mean layering their characters with an interiority that looks past their beauty to what lies within.

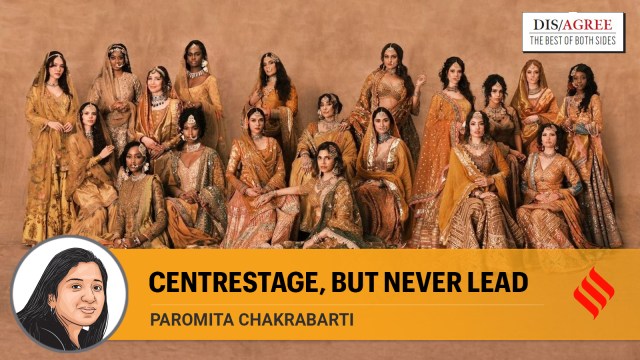

Bhansali’s films have women at the centre of the narrative but are they flag-bearers of feminism? Sorry, I will have to pass.

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com