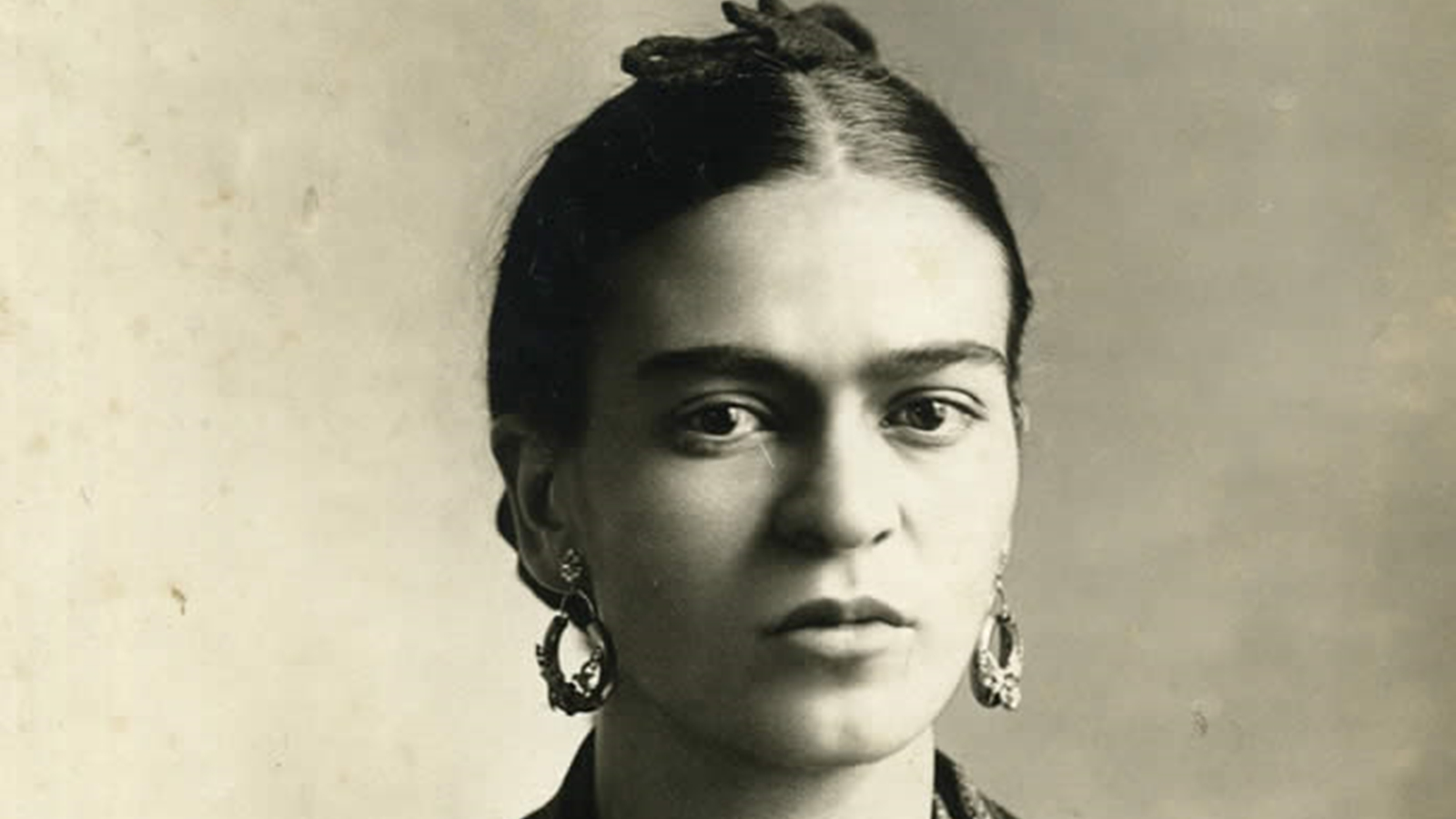

Frida Kahlo seems to be everywhere — embossed on dangly earrings, painted on tote bags, drawn on walls. Almost synonymous with the feminist zeitgeist of urban India and the West, she’s just as recognisable as the lady on the We Can Do It poster. Kahlo is seen as a symbol of strength for the modern, liberated woman — proud of her Latina heritage, a breaker of beauty stereotypes, and a staunch Leftist. Kahlo has all the trappings of being a modern cultural icon, much like Andy Warhol, and she was never one who shied away from fame.

But Kahlo also controlled the narrative, perhaps as an act of resistance. She denied Andre Breton’s labelling of her as a “surrealist”, claiming that she painted her reality. So how justified is the commercialisation of Frida Kahlo (something that can arguably be a shallow reimagination)? Does it dilute the values she spoke about during her lifetime? As she gained more popularity in the West, it was strange how the “hater of gringos” and an anti-capitalist was suddenly reduced to keychains, Converses, and bobbleheads — emblems that facilitate easy activism.

Kahlo suffered several physical afflictions – miscarriages, spinal defects, and bouts of polio. Her pain is never part of the contemporary narrative or any of the renditions. It is not very pretty. As seen in The Broken Column, where a steel brace props her up or her paintings depicting her miscarriages, art liberated her from physical trauma. That was her surrealism — an imagined escape where she was no longer suffering physical or emotional pain (a product of her relationship with Diego Rivera). However, male artists of similar commercial fame, like Vincent Van Gogh, never have their pain washed away. Van Gogh is remembered for his madness, moodiness, and maimed ear.

The Mexican artist is far from the “selfie queen” that headlines make her out to be, her portraits were never a project of vanity but one of freedom — from the pain of her public and private life. Some may argue this is the tradeoff for making art accessible. But where is the line between rendering art accessible and manufacturing pale imitations? Her art was after all the “frankest expression of herself” — eschewing its complexity cannot be fair.

Much nuance is lost in making Kahlo iconic and commercially viable. With a third of her artwork consisting of self-portraits, it’s ironic how she is often the victim of misrepresentation. Posters of Kahlo lighten her unibrow, and her skin – her “exoticism” is just enough, never too much. Her political radicalism is also subdued — as someone who called Marxism a crutch to her in illness, Kahlo’s Left-leaning ideology is mentioned, but never in fully acknowledged, nor is her disdain for the West.

Funnily, as her portraits are auctioned off at Sotheby’s and Barbiefied by Mattel, it’s easy to forget her activism against US interventionism, even towards the very end of her life. Her tryst with Leon Trotsky is rarely seen as an insight into how politics shaped her work, but simply a love affair. Fridamania also overshadows her critique – Mexican indigenous communities often accuse Kahlo of appropriating indigenous dress which is a common motif in her paintings. Kahlo, born to a German father and a Mexican mother, was only one-third indigenous. She has been criticised for promoting the Mexican nationalist policy of Indigenous assimilation led mostly by the Mexican elite – indigenismo. However, no one can deny that Kahlo highlighted the culture, again, as a form of resistance and perhaps, in search of her own lost identity. Her 1939 work, Two Fridas shows the juxtaposition of her complex ethnic identity – one in traditional Tehuacan wear, the other in modern. But the debate is not over appropriation here, it’s the fact that the debate itself is wholly ignored.

Kahlo has had many labels slapped onto her — surrealist, quirky, Diego Rivera’s wife — of which she chose none. For a woman who fought those who reduced her to her “eccentricism” and “exoticism” and physical anguish and personal upheaval, co-opting the artist for marketing ploys or easy activism is unjust. Art is for everyone, but what about the artist herself? Kahlo must live as herself in memory as she’d like to have lived.

The writer is an intern at The Indian Express