I first met Ratan Tata in the early 1990s, some years after he had taken over the chairmanship of Tata Sons from JRD Tata. At the time, many of the Tata companies were run like satrapies: Russi Mody controlled the Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO), Darbari Seth ran Tata Chemicals and Ajit Kerkar ran the hotels business. As JRD’s favourites, they ran their empires as they felt, and believed that they had the upper hand over the greenhorn head of Tata Sons. How wrong they were.

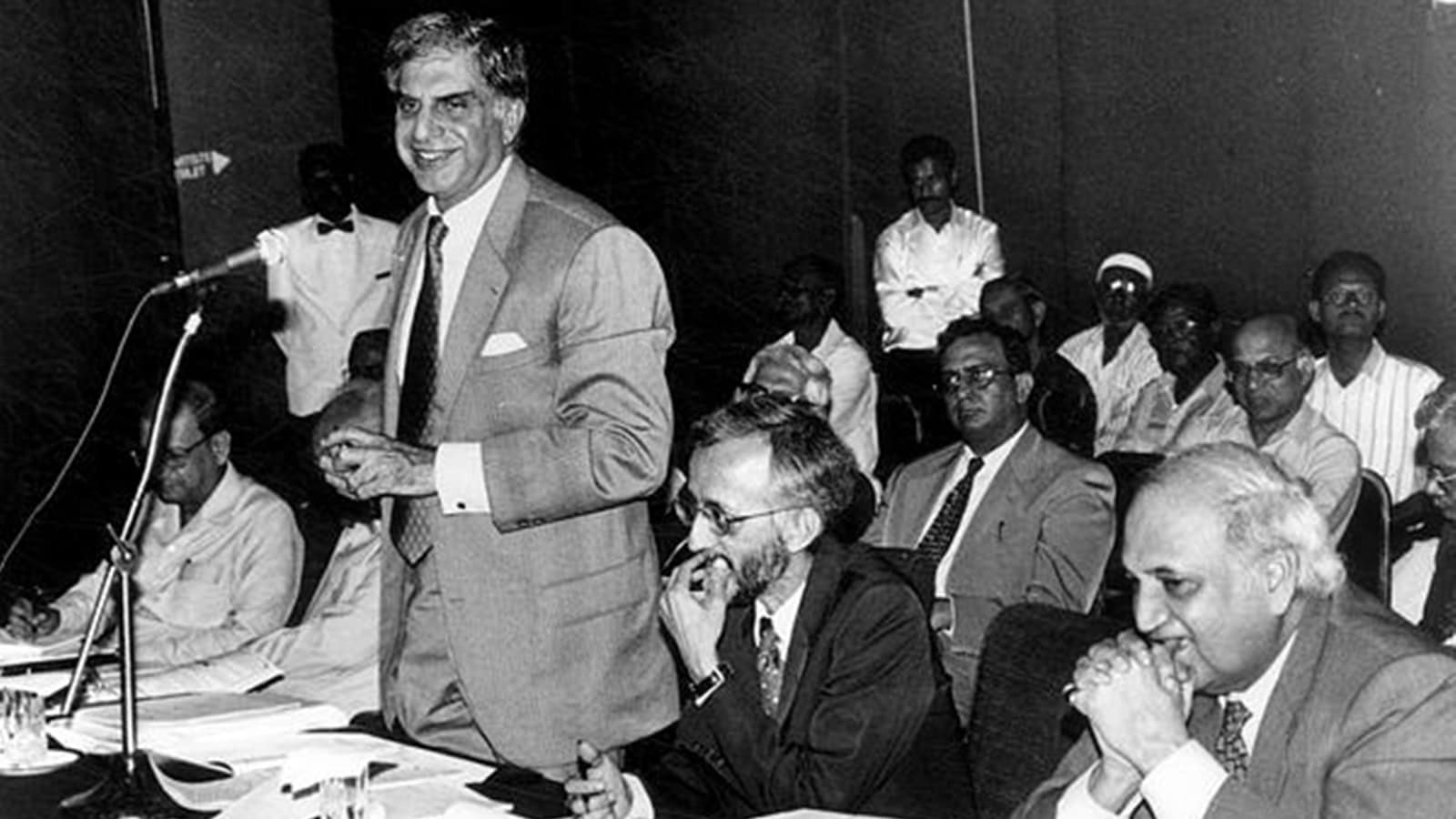

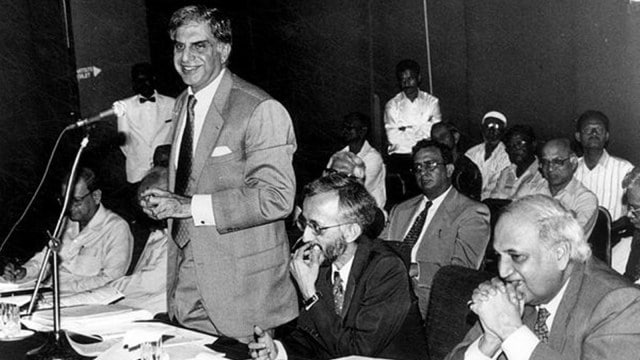

After a bruising battle, the seemingly gentle Ratan got rid of the toughest and longest-standing satrap, Russi Mody, in March 1993 by invoking the group’s forgotten retirement policy — directors older than 75 years had to go. Darbari Seth got the message and left, though he left his son Manu to succeed at Tata Chemicals. Kerkar was an altogether different story. He was much younger, so the retirement policy wouldn’t do. Moreover, Kerkar had created some 20-plus top-class hotels with little to no financial help from the Tata group and was hardly beholden to Ratan. I remember that battle well as I witnessed first-hand Ratan’s steel and tactical intelligence. As the chairman of Indian Hotels Company Limited (IHCL), he spoke with the key directors one-on-one to support his position. And then, at a board meeting of IHCL, the board ousted Kerkar instead of allowing him to retire.

In his early years at Tata Sons, Ratan faced several other problems. I remember three. The first was his desire to start an airline with Singapore Airlines. This was repeatedly blocked by Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways, who knew how to woo New Delhi’s ministers and bureaucrats far better than Ratan and forced the Tatas to give up. Vistara came later. The second was a large “donation” that the Tata group gave to the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), a militant organisation, presumably for the safety of the managers and staff of the Tata Tea estates in Assam. That blew up in his face, and it took a while to go away. The third were the directors he inherited at Tata Sons. Once, he invited me to Bombay House to give them a talk on corporate governance. It was a post-lunch meeting and Ratan warned me that most directors would be snoozing while I gave the talk. They did, and I couldn’t figure out how he could deal with these oldies. “It’ll take time, Omkar”, he said, “and has to be done one at a time”. Which he eventually did.

The most critical issue that faced Ratan was how little Tata Sons owned of the companies that carried the Tata name. Rarely was the stake higher than 20 per cent. Here, Ratan was fortunate to have his cash cow, the yet unlisted and highly profitable Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). Over the years, he used the free cash flow from TCS to hike Tata Sons’ shareholdings in all the key companies and thereby protect them against takeovers. It was only after this was achieved that TCS got listed in August 2004.

Amidst all this, Ratan triggered a series of global acquisitions. It started with Tata Tea taking over Tetley in the UK in 2000. In between several other international buys, came two monstrous ones: Tata Steel’s takeover of the Anglo-Dutch steel-maker, Corus, in 2007 for £6.2 billion; and Tata Motors’ purchase of Jaguar-Land Rover for $2.3 billion in 2008. Expensive to begin with and made worse by a brutal auction, the Corus acquisition turned sour — an aspirational mistake that could not be handled. In contrast, Jaguar-Land Rover was, and continues to be a major success.

Now, for the human aspects of Ratan. Let me share four. The first was when Pakistani terrorists attacked the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai on November 26, 2008. The whole world saw Ratan standing in front of the hotel until the last survivor was taken out. He then ensured that the relatives of the killed employees received salaries that they would have earned for the rest of their working lives; and visited their homes to ensure that their families were taken care of.

The second was his childlike love of planes and flying. I remember escorting Jaswant Singh to his office where, in the course of conversation, he discovered that Singh was flying back to Delhi the next day. So was Ratan; and he invited both Jaswant and I to accompany him on the plane. He took control at Santa Cruz airport and flew non-stop to Palam with Jaswant in the cockpit. Once, while awaiting a flight from Pune, he witnessed a number of Sukhoi jets take off and touch down. I then got a brilliant tutorial from Ratan about Sukhois, their thrust, their speed, their short take-off capability and much more. His dream of flying a jet fighter came true when he was handed over the controls of an F-16 at Bengaluru and he did some rolls and came down to 500 feet. The happiness on his face was beyond comparison.

The third was his simplicity. Until he became too old, Ratan would always drive his car in the evening without a chauffeur. He would carry his own luggage. I never saw flunkeys around him at airports. He would wait his turn to check in and go through the security check. I’ve seen him wheel a luggage cart at Heathrow Airport. He lived and quietly entertained in his apartment in Colaba, unlike others who built multi-storied palaces and palazzos in Mumbai.

And the fourth was his love for dogs. While he always had a brace of Alsatians at home, his love for all manner of stray dogs was second to none. Consequently, you entered Bombay House being greeted by a number of stray dogs who enjoyed the cool marble floors in summer. They were the lords of that office.

Ratan, we were blessed by a rare person such as you.

The writer is an economist, Chairman of CERG Advisory Private Limited, and serves on boards of listed companies