The shocking assassination attempt on former American president Donald Trump during an election campaign rally on the weekend has brought to the fore a fundamental crisis afflicting not just the United States (US) but many other countries worldwide. The episode is a reconfirmation that we are living in an age of extremes where centrist ideas like consensus, compromise, coexistence, and middle ground are collapsing and are being replaced by the notion that politics and public life represent a no-holds-barred struggle where one must give no quarter to the enemy.

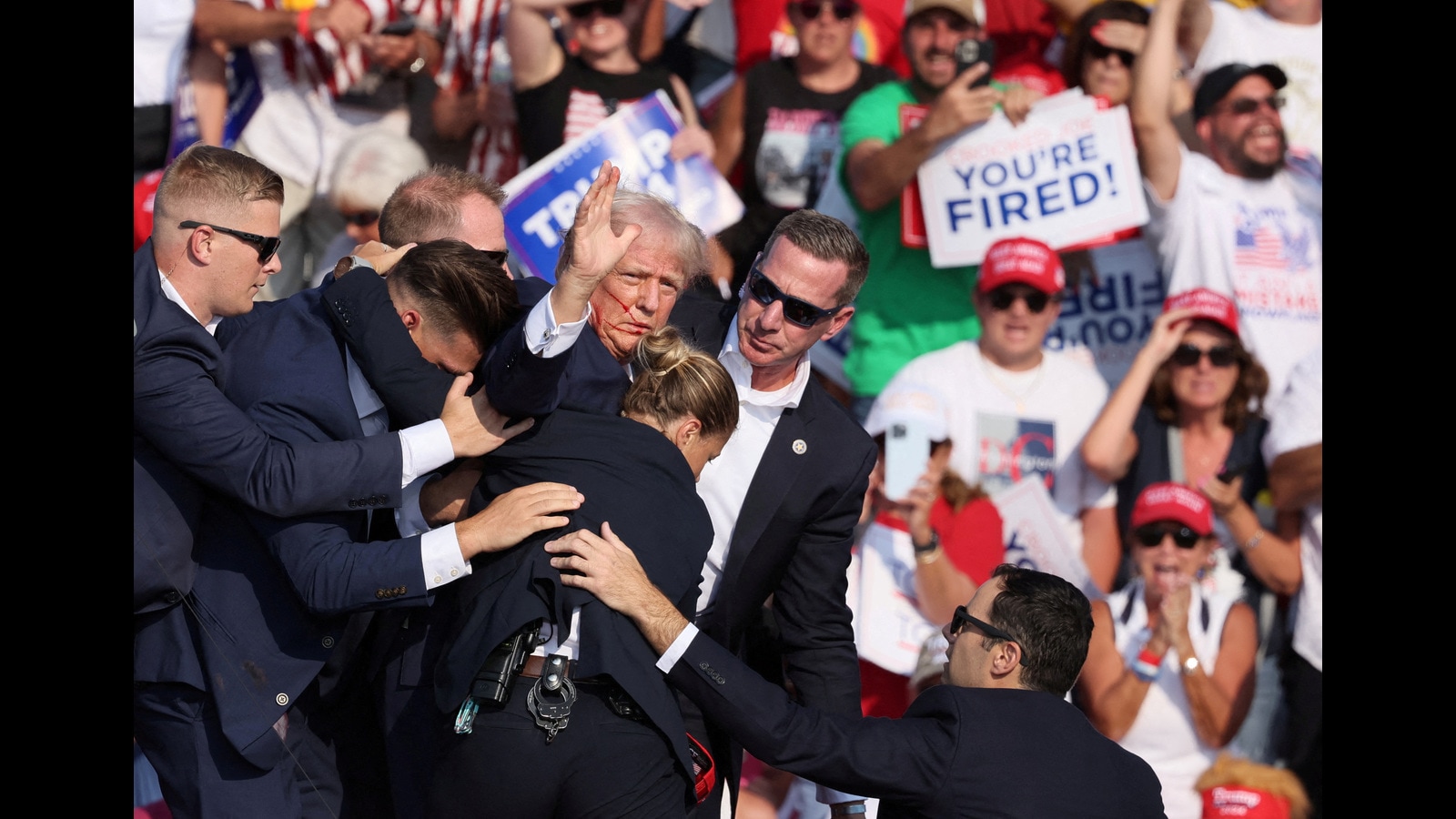

The dramatic visuals of a bloody-faced Trump, after narrowly escaping fatal injuries from gunshots, pumping his fist in the air and defiantly shouting “fight, fight” while facing the cameras, conveyed a lot. The 19th-century Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz wrote that war was a “continuation of politics by other means”. Today, in America and elsewhere in the democratic world, politics has become a continuation of war by other means. Politicians, political parties, and over-politicised individuals and groups believe they have no option but to prepare for existential combat with their opponents because, if they do not win, the other side will annihilate them and their values.

Following the attempt on Trump’s life, many American observers bemoaned their country’s “toxic political culture” and vicious polarisation. Incumbent President Joe Biden lamented a “sick” mentality that is spreading violence and appealed to “lower the temperature”. Former President Bill Clinton insisted that violence had “no place in our political process”, while another former President, Barack Obama, urged Americans to “use this moment to recommit ourselves to civility and respect in our politics”. Such comments may have been intended to remind the general public that politics must not cross the red lines of humanity and that conscious efforts needed to be made to unify the country around shared civic values.

But the attack on Trump is, if anything, only likely to further inflame the severe divisions roiling America. With a highly consequential presidential election at stake, hardcore Republican and Democratic loyalists have begun assembling their respective in-groups and settling into the familiar position of two inimical “tribes” battling and blaming each other for the shootout.

According to populist Right-wing narratives, the assassination attempt was the last resort in the liberal establishment’s long-standing witch-hunt to halt Trump’s return to power by hook or by crook. Allegations that Trump had been denied additional Secret Service protection by the Biden administration despite repeated requests have outraged conservatives who believe that the liberals are out to physically eliminate Trump. In Left-of-centre circles, claims that the assassination attempt had been “staged” as a false flag operation to garner sympathy for Trump did the rounds. Other liberals blamed Trump himself and his “red meat” style of provocative rhetoric for unleashing a brand of politics marked by anger and division, which is now spilling over into uncontrolled violence.

What makes the current era more troubling and intractable than earlier periods of political turmoil is that the classic Left-versus-Right ideological polarisation is being exacerbated by polarisation derived from other forms of dichotomies. Political scientists Jennifer McCoy, Tahmina Rahman and Murat Somer have argued that “societal polarisation” involving “us” against “them” segregation is happening along axes like “globalist/cosmopolitan versus nationalist; religious versus secular; urban versus rural; traditional versus modern cultural values” in many parts of the world. These complex divisions, often aggravated by anxiety related to globalisation’s unfair outcomes, cause communities to avoid intermixing and instead huddle into narrow echo chambers and filter bubbles where conspiracy theories and bitter portrayals of “enemies” abound. Such fragmentation leaves people devoid of any sense of common citizenship or overarching national identity.

The phenomena of “algorithmic radicalisation” on the internet that amplifies negative stereotyping, and of self-selective social media communities that build up fear and loathing of those allegedly plotting to snatch away one’s rights and freedoms, have added a layer of technological polarisation to the already combustible mix.

With so much unregulated and non-moderated content circulating on the internet, where search engines are commercially rigged to favour incendiary content that whips up raw emotions, the resort to political violence is also getting atomised. Any self-radicalised netizen who has access to weapons can carry out lone wolf attacks based on personal convictions, without the prodding of powerful organised entities.

It is worth recalling that, in recent years, other high-profile politicians such as Prime Minister Robert Fico of Slovakia, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, and former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of Argentina were also attacked in open public spaces by individuals who vehemently disagreed with their victims’ policies on issues as wide-ranging as endorsement of religious movements, excess concentration of power, and distribution of social welfare to the poor.

Given the multiple overlapping types of polarisation and the relentless spread of online hatred, it is no wonder that politics is getting more violent and less cordial, not just in the US but elsewhere, too. Even in countries where there is no gun culture or a history of racial or other ethnic cleavages and resentments, risks of frequent outbursts of politically motivated violence are rising due to the general breakdown of civic culture and the multifaceted backlash against the iniquities generated by globalisation.

After the attack on Trump, many thinkers expressed alarm that democracy was in mortal danger in America. But the political system is a reflection of deeper fault lines. Unless individuals, societies, and governments systematically acknowledge, identify, and redress underlying socioeconomic and technological factors fuelling feelings of hatred, vengeance, and despair, we cannot expect a return to gentler, accommodative, and decent politics.

Sreeram Chaulia is dean, Jindal School of International Affairs. The views expressed are personal