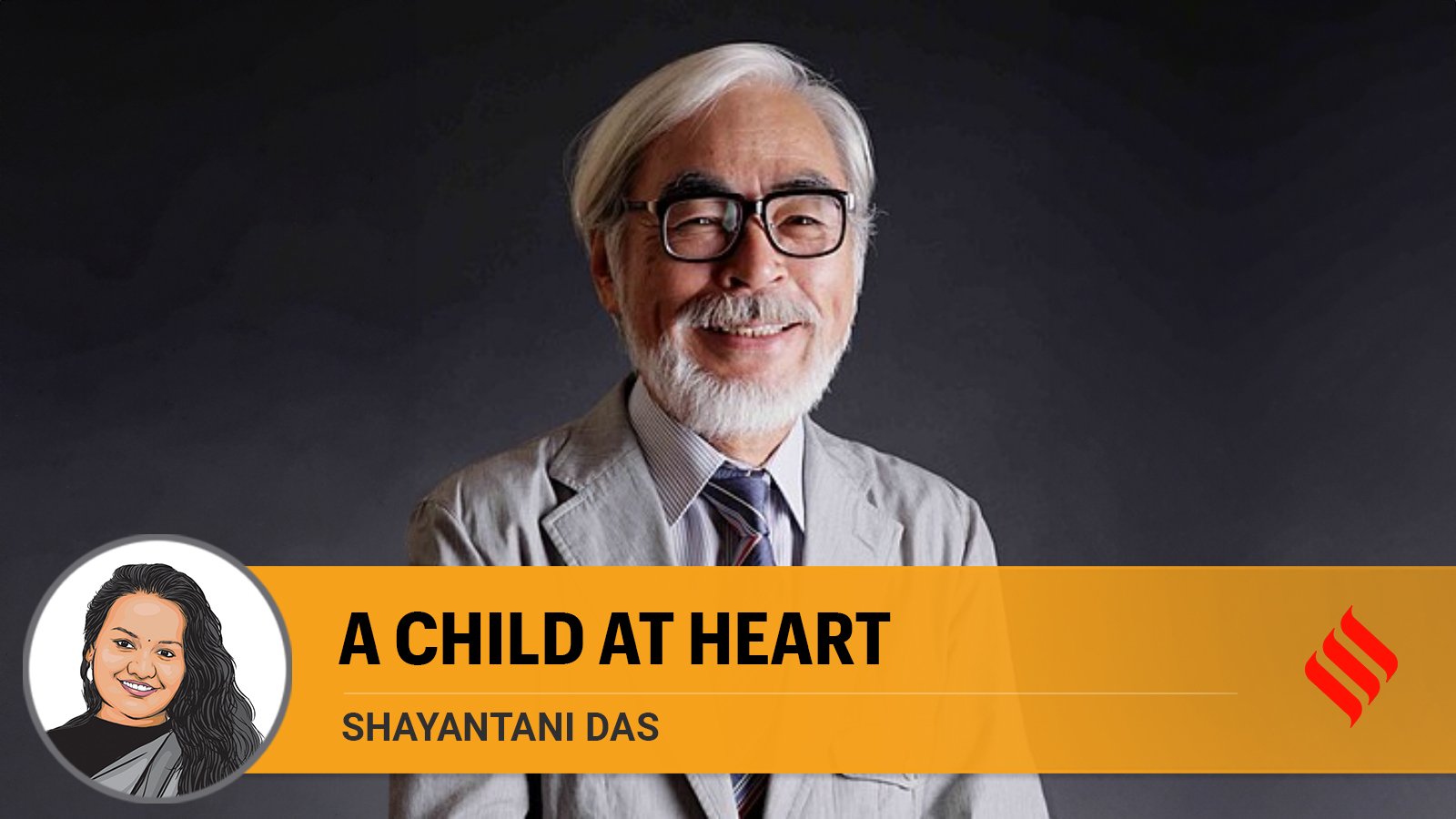

Every year, the Ramon Magsaysay Award recognises the “greatness of spirit shown in selfless service to the peoples of Asia…” One of this year’s recipients, Hayao Miyazaki, embodies this spirit. The co-founder of Studio Ghibli, director of 12 animated feature films, and a manga artist, is widely celebrated as one of the greatest visionaries in the history of animated cinema. Starting with The Castle of Cagliostro in 1979, Miyazaki’s work has constantly displayed the wisdom of a philosopher, the craftsmanship of an artist, and the heart of a child.

While his films are not exclusively for children, watching a Miyazaki film feels like stepping into childhood. Perhaps it is the delightful beings that populate his narratives: Cat buses that rumble past, castles that float and belch steam, and soot sprites that dance on their tiny feet. Or, it is the courageous young heroes and heroines — a boy with a pig snout flying an airplane, a young girl trapped in a spirit world, a teenage witch in training. The beauty of each frame, from sun-dappled forest to cloud-speckled skies and otherworldly spirit realms, is a testament to his years of apprenticeship as a hands-on animator.

But beyond each frame’s beauty lies an ominous darkness, often war and ecological crisis. In Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), idyllic skies are obscured by smoke from warplanes while in Princess Mononoke (1997), the gods and spirits of a forest clash against the humans who drain its resources. The natural world is full of forces both gentle and vengeful. Even his quietest film My Neighbor Totoro (1988) is set against real-world anxieties that infiltrate a children’s world like a parents’ illness, loneliness, and change. As a filmmaker, he offers his young audience comfort without talking down to them. His soft world-building invites viewers to fill in the gaps with their imagination, showing deep respect for the emotional complexity and curiosity of children.

A recurring thematic concern in his work is the mixed blessings of technological progress. His characters walk in the air, on brooms, or on the back of winged spirits. But often flights of fancy are replaced by literal aerial adventures. In one of his early films, Porco Rosso (1992), the titular character is Marco, a disillusioned fighter pilot turned bounty hunter, who has been cursed to live as a pig. Set against the rise of Mussolini’s fascist regime, Marco suffers from survivor’s guilt. His meticulously maintained red plane stands both for personal defiance and a gateway to his pre-war memories.

Miyazaki is even more explicit in his exploration of this theme in The Wind Rises (2013). The film follows Jiro Horikoshi, the aeronautical engineer who designed Japan’s Zero fighter plane used in World War II. Jiro dreams of majestic aircraft crisscrossing dream-like skies. He laments to his idol, Giovanni Caproni, that none of his planes ever returned. Caproni’s response, “There was nothing to return to. Airplanes are beautiful dreams. Cursed dreams, waiting for the sky to swallow them up,” encapsulates the central dilemma — beautiful things, feats of engineering, technological advances are also tied up with their catastrophic application. Miyazaki’s multitudes of lovingly drawn aircraft represent human ingenuity and freedom, but they also represent war and modernity.

These calamitous forces — fascism, war, and ecological collapse — often replace traditional epic villains in Miyazaki’s films. These forces are a threat to the world and not just the protagonist. When antagonists do appear, they are often redeemed — not necessarily by their actions, but through the protagonist’s acceptance and empathy. In Spirited Away (2001), Chihiro never directly confronts the powerful Yubaba, ruler of the bathhouse. As a young girl who possesses no magic, this effort would anyway be futile. Instead, she is clever, resourceful, and kind, and her actions culminate with her calling Yubaba “granny” before her return to the human realm.

Miyazaki’s heroes and heroines are brave but not in the obvious ways. It is a quiet, hesitant, tentative courage, a mix of stoicism and vulnerability. At 83, The Boy and the Heron released last year may be his last. His legacy will not just be his extensive body of work but also his way of seeing. As the world moves towards environmental ruin and gives in to the lure of authoritarianism — threats Miyazaki has long foreseen — his films will continue to invite audiences to look around not just with cynicism but also with wonder and quiet courage.

The writer is assistant professor, Department of English, Hindu College, University of Delhi

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 07-09-2024 at 07:10 IST