Taxing wealth is not a recent phenomenon. The canton of Basel City in Switzerland had introduced such a tax way back in 1840*. The Netherlands began to impose the tax in 1892. Sweden in 1911. In India, T T Krishnamachari, minister of finance, introduced the wealth tax in 1957. Several other countries also levied the tax.

But, somewhere along the way, the wealth tax went out of vogue. The number of OECD countries levying the tax fell from 12 in 1990 to four in 2017. And in India, the wealth tax was abolished in 2015.

In recent years, however, there appears to be a renewed conversation on taxing wealth. Soaking the rich, after all, has enduring appeal. More so when estimates point towards the growing concentration of wealth and income in the hands of a few.

In their recent study on India, Thomas Piketty and his co-authors have documented a sharp rise in inequality in India over the past decades — a rise that appears to be more pronounced post 2014-15. As per their analysis, the top 1% accounted for 22.6% of income and 40.1% of wealth in 2022-23. These estimates place the income share of the top 1% in India even higher than that in South Africa, Brazil and the US.

Juxtapose the gains made by the top 1% against the meagre earnings of those at the lower ends of the income distribution who are dependent on state programmes and schemes — for instance, those who receive free/subsidised foodgrains or seek work under MGNREGA — and the appeal of such taxes becomes obvious, especially as only a minuscule percentage of the population is

likely to be affected by it. Such a tax, it is argued, would raise more resources which could be used to provide greater support to the poor while also addressing concerns over rising inequality and progressivity of the tax system.

Piketty and his co-authors have argued in favour of imposing a 2% annual tax on net wealth exceeding Rs 10 crore and a 33% inheritance tax on estates in excess of Rs 10 crore.

However, there are several problems with imposing such taxes, as India’s own history with both the wealth and the inheritance tax have shown.

Such taxes are difficult to implement. They entail high administrative costs, can lead to excessive litigation and tend to raise very little revenue — the rich have always found creative ways of gaming the system. In fact, the problems with such taxes have been acknowledged by finance ministers from both sides of the political spectrum.

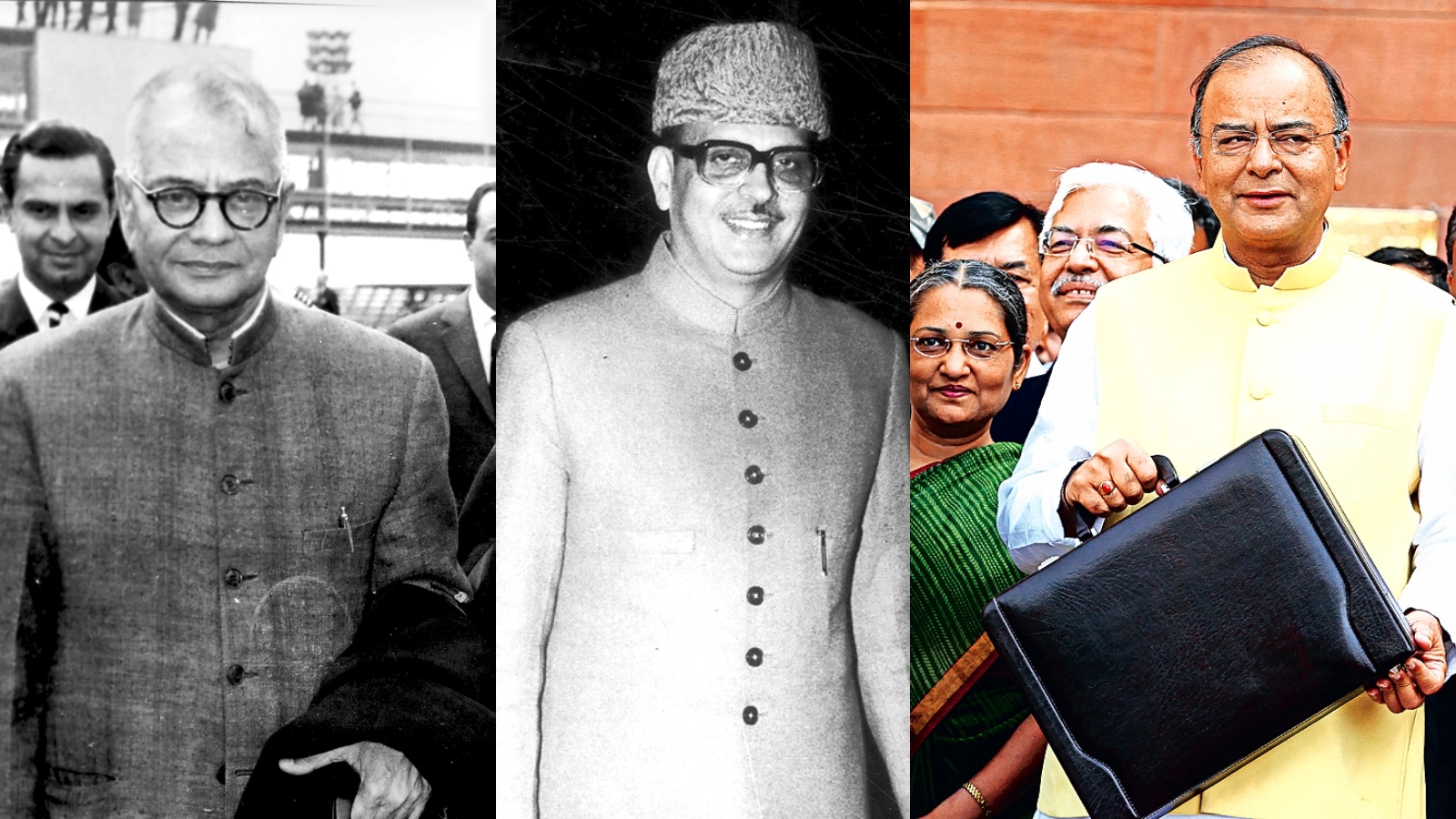

In 1985, when V P Singh abolished the estate duty, or the inheritance tax as it was then known, he acknowledged that the cost of administering it was “relatively high”and the revenue collected was “only about Rs 20 crore”. Singh, who was finance minister in the then Rajiv Gandhi led Congress government, further noted that the tax had “not achieved the twin objective with which it was introduced, namely to reduce unequal distribution of wealth and assist the states in financing their development schemes.”

Similar views were echoed by Arun Jaitley three decades later, when he abolished the wealth tax. In his 2015 Budget speech, Jaitley said: “The total wealth tax collection in the country was Rs 1,008 crore in 2013-14. Should a tax which leads to high cost of collection and a low yield be continued or should it be replaced with a low cost and higher yield tax?” In that year, total collections through the tax amounted to less than 0.1% of the government’s tax revenues.

most read

Since the time there have been taxes, there have been those trying to evade them. A papyrus from ancient Egypt (7th century BCE) reveals the story of a man who was transferring his property to his children at a conservative value. His objective was simple — to evade the inheritance tax. The punishment for such evasion — whipping. Such stories recounted in the book Rebellion, Rascals and Revenue are insightful for they detail not only the myriad ways in which rulers have always tried to extract resources from the people, but also the ingenious ways in which people try to evade paying taxes.

In today’s globalised world, with few restrictions on the mobility of capital, there is also the very real possibility that high rates of taxation will simply result in the rich leaving the country, opting instead to settle and conduct their business from cities such as Dubai. This will have implications for the country’s economy.

The risk of capital flight is not an exaggerated, trivial concern. Various reports suggest that after Norway increased its wealth tax, many high net worth individuals left the country. India has also been experiencing a flight of the rich. In 2023, around 5,100 Indian millionaires relocated abroad as per a report by international investment migration advisory firm Henley & Partners. Among the various reasons why people choose to migrate are financial considerations and tax benefits. A wealth or an inheritance tax may aggravate this. Moreover, a large part of wealth in India, and as a consequence a person’s inheritance, is in the form of land, real estate and gold. Will these have to be liquidated? India’s story of wealth creation has just started. Millions are only now beginning to take part in this journey. Levying such taxes will only take us back to our socialist past.

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package