For decades, international NGOs (INGOs) have pushed donor-driven agendas that have often harmed local communities. In Tanzania and Kenya, INGO-led conservation displaced Maasai communities. In Bolivia, water privatisation in Cochabamba, backed by INGOs, restricted access, leading to public outcry and policy reversal. Similar patterns have emerged in India, where INGOs promoted projects with conditions that ignored local realities, undermining development goals.

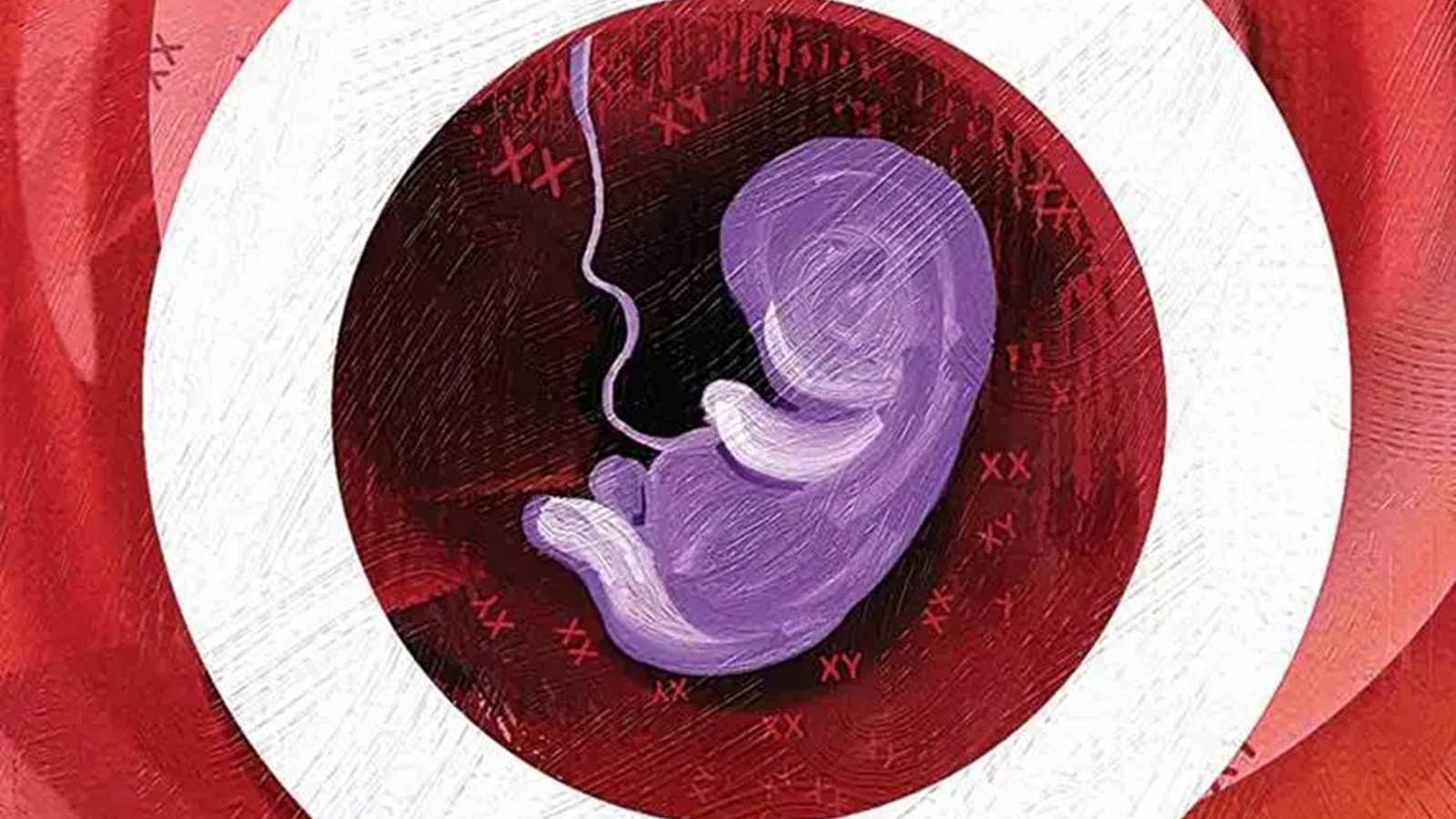

More of us should read Unnatural Selection by Mara Hvistendahl. It sheds light on how interventions by INGOs led to an increase in the incidence of female foeticide in India. While the Western narrative tends to focus on how cultural preferences in India have fuelled this tragic practice, it conveniently ignores the historical role of British colonial policies and Western NGOs in perpetuating gender imbalance on an industrial scale.

Scholars such as L S Vishwanath and Bernard S Cohn have shown that British land reforms in the late 18th and early 19th centuries directly increased infanticide among land-owning castes. Nevertheless, the British perpetuated the narrative that female infanticide was rooted in India’s cultural backwardness. After Independence, the so-called “white man’s burden” was perpetuated by INGOs pushing donor-driven agendas, often reflecting the same colonial mindset. Their interventions — driven by Malthusian fears of overpopulation — ended up worsening female foeticide.

Between the 1950s and 1980s, INGOs such as the Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, and Population Council played a central role in introducing sex determination technologies to India. By the 1960s, India’s population was seen as a major global concern, and Western experts identified it as a “test case” for population management. In 1975, egged on by INGOs, 59 per cent of India’s Health Ministry budget was directed toward family planning, with little left for pressing needs like tuberculosis and malaria. The introduction of amniocentesis tests at AIIMS, which were initially meant to detect fetal abnormalities, quickly became tools for determining foetal sex.

A key figure in this was Sheldon Segal, head of the Population Council’s biomedical division, who was posted to Delhi with backing from the Ford Foundation. Segal was directly advising Lieutenant Colonel B L Raina, India’s director of family planning. Segal helped reorient Raina’s focus solely on population control. By 1965, personnel from the Ford Foundation alone in Delhi rivalled the US embassy staff in size, and the Rockefeller Foundation had its largest presence outside the US in New Delhi. The economic leverage these INGOs wielded cemented their control. By the 1960s, India was receiving $1.5 billion annually in aid, much of it conditioned on population control measures.

INGOs also established strongholds in prestigious institutions to make pliable Indians to fight the “intellectual battle” on their behalf. For instance, the Population Council established India’s first demography centre at the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, while Western funding focused heavily on AIIMS, where Segal set up a department of reproductive physiology. The Rockefeller Foundation had embedded advisers at AIIMS since 1958, and the Ford Foundation began backing the institution in 1962 with a $1.7 million grant.

Nudged by these INGOs, at AIIMS, doctors openly promoted the use of sex determination technology. A paper published by I C Verma and colleagues in Indian Paediatrics defended the use of amniocentesis for sex selection, arguing that it could help reduce “unnecessary fecundity” by allowing families to stop reproducing once they had a male child. The paper acknowledged that 7 out of 8 families that underwent the test primarily for sex determination chose to abort female foetuses. By 1978, over 1,000 female foetuses had been aborted at AIIMS alone, and between 1978 and 1983, an estimated 78,000 female foetuses were aborted nationwide as sex determination spread to other government hospitals. In other words, the INGOs were fully aware of what they were promoting.

Census data reveals a troubling decline in the child sex ratio over the decades, with a particularly sharp fall after the 1970s. In 1951, the ratio stood at 943 girls per 1,000 boys, close to the natural sex ratio of about 950. The ratio decreased to 941 in 1961, 930 in 1971, and 934 in 1981. By 1991, it had further dropped to 927. Notably, the most significant decline occurred in 1971, closely coinciding with the introduction of sex-determination technologies and amniocentesis tests in India during the late 1960s. Incidentally, these INGOs also funded the import of ultrasound machines to India.

Studies reveal that states with easier access to sex-determination tests saw sharper declines in the female-to-male ratio. By 2001, early adopters like Punjab and Haryana experienced drastic drops in their child sex ratios — Punjab to 876 and Haryana to 861. Both states are close to Delhi, the headquarters of these INGOs. According to a 2006 study by Jha et al., published in The Lancet, the introduction of prenatal sex-determination technologies led to an estimated 10 million missing female births in India over two decades. The study noted that between 1980 and 2010, an average of 5,00,000 female foetuses were aborted annually.

The female foeticide often blamed on traditional Indian values can be traced directly to colonial policies, later weaponised by INGO advocacy. This is not to deny the existence of traditional biases but to highlight that large-scale foeticide resulted from deliberate actions by agencies that now lament the issue. Gender imbalance in India is just one example of how external agencies, even when they have good intentions, can cause lasting harm. Therefore, local policymakers must exercise caution and scepticism when considering advice from INGOs and consultancies.

Debroy is Chairman, Sanyal is Member and Sinha is OSD, Research, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister. Views are personal