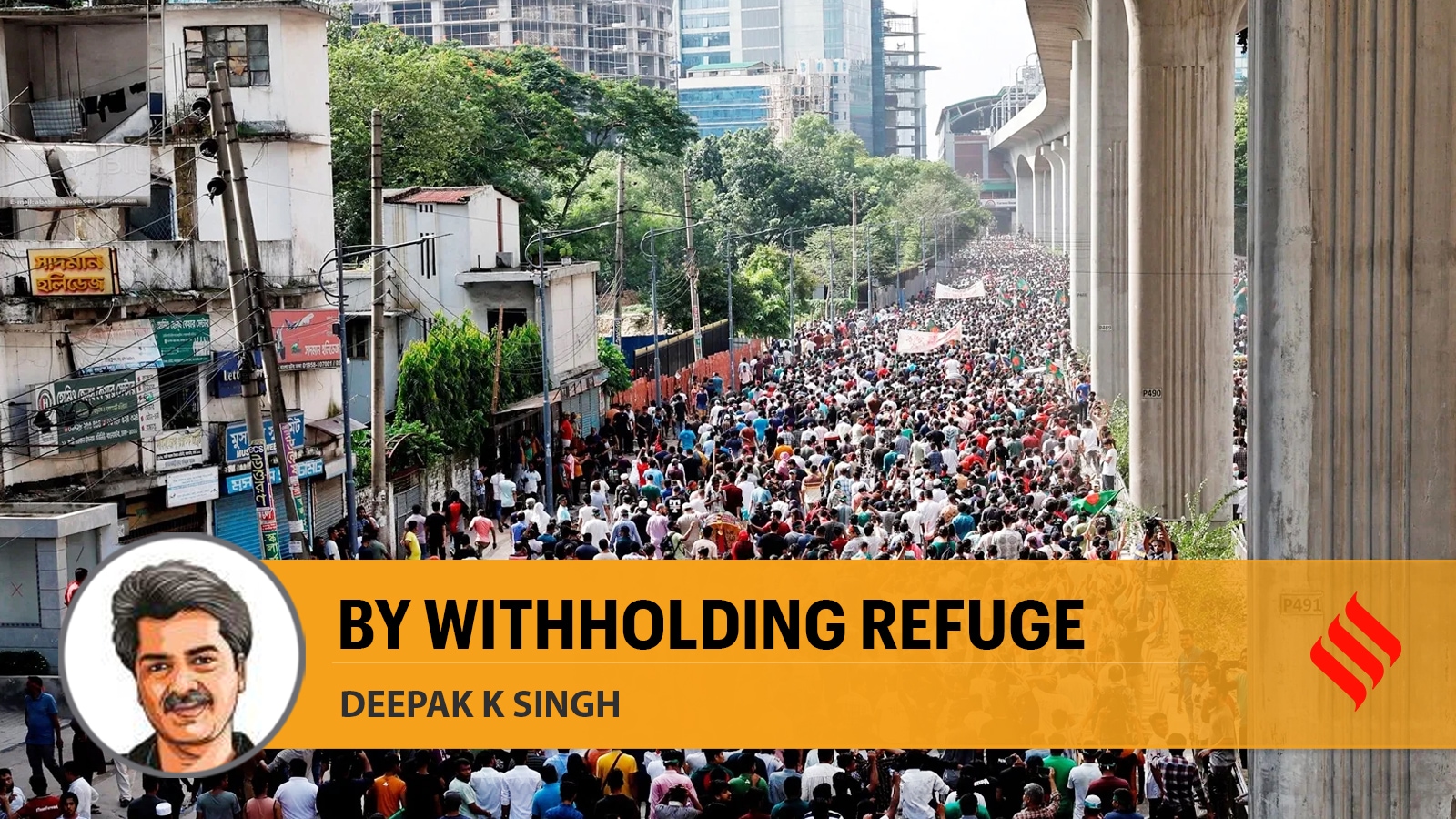

When Sheikh Hasina dialled New Delhi on August 5, with a frantic appeal to be allowed into Indian territory, the Government of India’s decision to allow her safe passage was, perhaps, the only available option under the circumstances. What weighed in favour of the Centre’s decision to allow Hasina into the country was, no doubt, her unambiguously warm and friendly relationship with India over the years, and her crusade against religious extremism and terrorism, resulting in a severe crackdown on anti-India militant outfits operating from Bangladesh. In sharp contrast, its subsequent decision to deny asylum to the persecuted Bangladeshi minority Hindus in India goes against its consistently held position of making India the “natural home of persecuted Hindus around the world”. Reports continue to pour in about the ongoing religious persecution of minority groups in Bangladesh, with scores of Hindu teachers being forced to resign and other officials and academics being racially profiled.

Reportedly, there have been as many as 205 cases of attacks on members of the minority communities in Bangladesh after August 5, with five confirmed cases of deaths. Neem Chandra Bhowmik, president of Bangladesh Hindu, Buddhist, Christian Unity Council in an interview (‘5 dead, 200 incidents: Fear grips Hindus in Bangladesh, leaders meet Yunus today’, IE, August 14) said: “We have been getting reports of vandalism, intimidation and threats on telephone from 52 of the 64 districts; the situation is dynamic… we are constantly trying to verify them.”

The denial of refuge to the persecuted minority groups is also inexplicable given the fact that it is the same government that had recently enacted the controversial Indian Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019. The CAA, which is a law of the land now, allows members of religious minorities — the Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis, and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who came to India before December 31, 2014 — to apply for the grant of Indian citizenship on grounds of religious persecution in their respective countries. While the central government might find itself hamstrung by its own cut-off date in extending the benefits of such a law, it could still have granted temporary refuge to the beleaguered Bangladeshi minorities seeking asylum. So out of sync with its stand is the current practice that some vocal pro-BJP supporters have begun asking why the government is not accepting the persecuted Hindus despite mounting evidence of atrocities against them.

However, the likelihood of granting refuge to the persecuted minority Hindus, about whom much concern is being expressed by government functionaries as well as members and supporters of the NDA, is rather slim. As evident from the official Indian government’s response posted on X by Home Minister Amit Shah, “In the wake of the ongoing situation in Bangladesh, the Modi government has constituted a committee [instead] to monitor the situation in the strife-torn country and along the India-Bangladesh border. The committee will maintain communication channels with their counterpart authorities in Bangladesh to ensure the safety and security of Indian nationals, Hindus, and other minority communities living there. The committee will be headed by the ADG, Border Security Force, Eastern Command.” Reportedly, the government has deployed BSF personnel at the land borders who have “peacefully foiled” an attempt by hundreds of Bangladeshi Hindus to enter India.

Denying persecuted Hindus, as well as other minority groups, a refuge in India flies in the face of its otherwise impeccable track record of being a generous host to refugees. The spate of recent attacks on minorities in Bangladesh constitutes solid legal ground for the grant of asylum even though India is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol. Not being a signatory does not absolve India of its commitment under customary international law to extend the much-needed succour to hapless asylum seekers.

Further, granting refuge to persecuted religious minorities from Bangladesh would have only been in line with India’s past track record, which remained consistent regardless of the parties ruling at the Centre. India had extended asylum to 10 million East Pakistani refugees in the wake of the liberation struggle in the erstwhile East Pakistan, an overwhelming majority of whom had returned to their homes in the newly independent Bangladesh. India was not a signatory of the 1951 Convention then as well. This time around, the number of Bangladeshi nationals seeking refuge was much smaller, running into a few thousand. The difference in the historical contexts between then and now is also evident. That India could afford to host such a large number of refugees then without much international aid and despite being a poor developing country was universally hailed as a welcome, proactive, and sensitive gesture towards people in desperate need of help. Much before this, India had also welcomed the Tibetan, Chakma, and other smaller groups of refugees.

Given such a backdrop, India’s current unwillingness to host religious minority groups signals a major policy shift. Considering the political instability in India’s neighbourhood, a hardened stance on refugees could have significant humanitarian costs and also diminish India’s stature internationally.

The writer is is professor, Department of Political Science, Panjab University, Chandigarh and author of Stateless in South Asia: The Chakmas between Bangladesh and India

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 10-09-2024 at 08:00 IST