Sanjib Kalita

Feb 21, 2025 11:15 IST First published on: Feb 21, 2025 at 11:15 IST

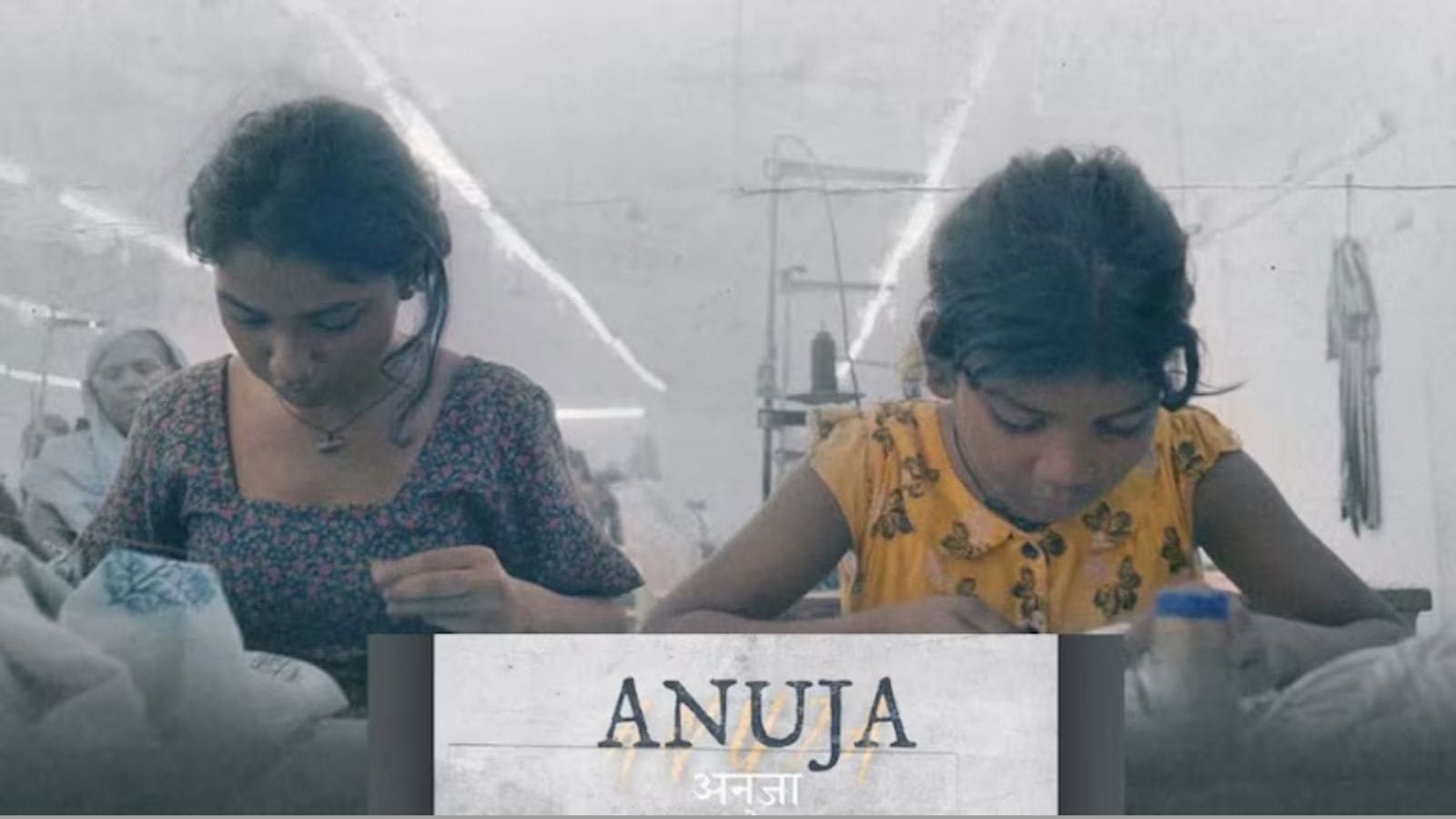

From a blurred visual, the camera focuses on a hut; in the background, one can see the vague structure of large multi-storeyed buildings, suggesting a place near the city yet distant from it, both literally and metaphorically. It is as if the director wishes to take the urban audience to a world close to them but less appealing, more arduous, and surrounded by fewer means of life. Then, the camera pans to two sisters, laughing and playing in slow motion. The director seems to emphasise the aesthetic sense of the moment by showing the lead character running her fingers across a bricked wall. Suddenly, the scene cuts harshly to a factory, where a man blows a whistle, its sound slicing through the air, demanding, without words, that the women focus on their sewing machines. The camera then moves through a series of establishing shots: Old women with tired hands, young girls with distant eyes, all hunched over their machines, stitching endlessly. Among them are the two sisters, quietly working, just like the rest.

Anuja, which has been nominated for Best Live Action Short Film at the 97th Academy Awards, is the story of two sisters trapped between a life of limited means they have inherited and an appetite for a fuller life that they both long to experience. The film beautifully captures the nuances of their struggle to break free from their present circumstances.

Story continues below this ad

Director Adam J Graves, who has done academic work in South Asia and is familiar with Indian culture through his research, has no doubt beautifully portrayed the story of the two sisters with different dreams, both of whom are accommodating and understanding of each other’s aspirations. However, the narrative might leave the audience uncertain — its emotional register fails to make it clear whether the filmmaker’s approach leans more toward sympathy or if his empathy for the subject truly comes through.

A major concern while watching Anuja is how it fits into the long-standing trend of Western filmmakers telling stories about poverty in the Global South. The film follows a familiar pattern where a narrative of hardship and struggle, set in a developing country, is packaged for an audience largely away from these realities. Western media representations of poverty often function within a sensationalist framework, designed to evoke sympathy while reinforcing a divide between the “privileged observer” and the “suffering subject”. These narratives do not necessarily seek to challenge structural inequalities but instead offer a digestible, emotionally compelling spectacle of struggle that conforms to Western expectations of the “Third World”.

Graves’s decision to focus Anuja on two sisters trapped in poverty follows a long tradition of films that turn hardship into something visually aestheticised and emotionally moving for Western audiences. The fact that Graves gifted plastic Oscar statuettes to the young actors before filming even began suggests an implicit awareness of how such narratives are received by the Academy. It raises the question: Was Anuja made, consciously or unconsciously, with an eye toward awards recognition? Does the film genuinely offer a critical engagement with the realities of poverty, or does it conform to the marketability of struggle as a cinematic theme?

Story continues below this ad

An Oscar certainly gives a filmmaker unparalleled fame and raises the market value of a film. Therefore, in the “film market”, an Oscar is considered the barometer of a film’s quality. Filmmakers and audiences are conditioned to think highly of this honour, and filmmakers are often drawn toward the validation they expect from the Academy. Slumdog Millionaire, which won eight Oscars at the 2008 Academy Awards and received significant attention from American audiences, is one such case in point. On the other hand, Salaam Bombay!, despite having a nearly identical premise, did not receive any recognition from the Academy Awards in 1989. This leads us to question whether a Western filmmaker’s portrayal of a developing nation is more validated than an Indian filmmaker telling a story from within. This points us toward an understanding that films about poverty and struggle often gain wider acceptance when shaped through an outsider’s gaze that caters to Western sensibilities.

most read

In this case, Graves seems to be well aware of India’s history with the Academy Awards and strategically chose a story from the country, sugar-coating it with emotionally wholesome scenes. With producers like Guneet Monga, who has already won an Oscar for India, and Priyanka Chopra, now an international celebrity, he seems to have found the right backers for the film at an international forum.

In the plot too, Graves’ attempt to “Bollywoodise” the story can be seen, in his inclusion of an old Bollywood song, Ude jab jab zulfein teri, that plays when the two girls go to watch a movie at the theatre. By including it, Graves seems to be seeking validation from the Indian audience as well. So, the film carefully balances and ticks all the right boxes — mesmerising Indian audiences with a wholesome story about two girls while appealing to American sensibilities by portraying a story of deprivation in a developing nation. The question however remains: Are Western filmmakers telling stories of poverty and struggle in the Global South out of a genuine commitment, or are such films calculated moves to secure recognition from the Academy Awards?

Kalita is a researcher on an ICSSR research project at Bodoland University