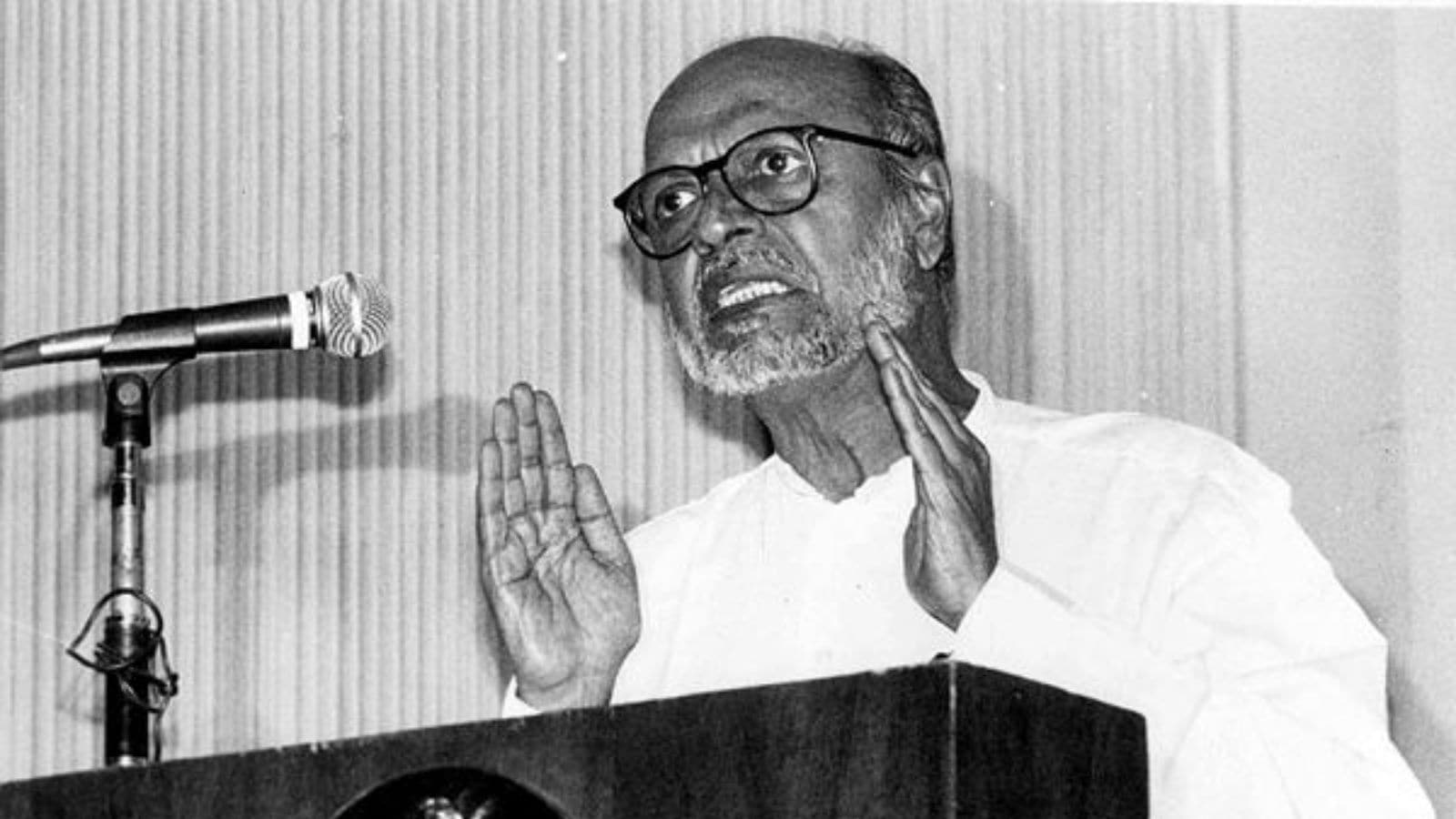

In the 1970s, when the country was witnessing political upheavals — bold assertion of caste- and class-based consciousness — Indian films were not left untouched. A few filmmakers, influenced by the European auteurs and neorealism, tried to call a spade a spade. Shyam Benegal (1934–2024) was one of them. He not only captured the nuances of power dynamics in rural India, he made the audience experience the complexities of human relationships, challenging the formulaic escapism of Bollywood. His thematic preoccupations, stylistic innovations, and enduring legacy positioned him as a foundational figure in the parallel cinema movement.

Complexities of caste, class and gender relationships had never escaped Benegal’s “camera-pen”. If Vishwam’s obsession with Sushila in Nishant (1975) brought attention to the reality of feudal society beyond the Gandhian imagination of a serene rural world, Ankur (1974) explored the psychosocial aspect of caste oppressions and systemic inequities.

Class and caste always operate in the framework of gender. Though Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw came up with the concept of intersectionality in 1989, Benegal’s women characters fought every aspect of marginalisation — from patriarchy to class and caste. Films like Bhumika (1977) and Mandi (1983) offered nuanced depictions of women navigating societal constraints.

In Bhumika, inspired by the life of actress Hansa Wadkar, Benegal critiques patriarchy while exploring the personal agency of women. Usha in Bhumika and Bindu in Manthan (1976) give testimony to women’s economic contributions and resilience. His collaborations with iconic actresses like Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi elevate feminist storytelling in Indian cinema.

In Benegal’s words, “Political cinema will only emerge when there is a need for it.” And he has always been true to what he said. Intertwining historical narratives with contemporary issues, he made The Making of the Mahatma (1996), depicting Gandhi’s formative years in South Africa. He humanised Gandhi, emphasising his philosophical evolution beyond the prevailing hagiographies. Similarly, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2004) offers a balanced portrayal of the controversial nationalist leader, encouraging critical engagement with history. The television series Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Nehru’s The Discovery of India, is a landmark in historical storytelling, blending cultural, religious, and political narratives to reflect on India’s pluralistic identity. This series remains relevant for its balanced approach to India’s complex past, challenging selective historical interpretations.

His stylistic hallmark is his commitment to minimalism, realism, and layered storytelling. Rejecting Bollywood’s grandeur, his films embraced naturalistic settings and subtle performances. Collaborations with actors like Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, and Smita Patil enhanced the authenticity of his narratives. Music in Benegal’s films played a supporting role, enhancing emotional depth rather than serving as a spectacle. Visual realism, achieved through natural lighting and location shooting, characterised his collaborations with cinematographer Govind Nihalani. Benegal’s rejection of melodrama and focus on humanistic storytelling ensured his work resonated emotionally and intellectually.

Benegal’s influence on contemporary cinema is multifaceted, encompassing thematic, stylistic, and ideological dimensions. His body of work continues to inspire filmmakers who seek to interrogate social structures, craft nuanced narratives, and embrace cinematic realism. His politically-charged storytelling has set a benchmark for contemporary filmmakers like Nagraj Manjule and Meghna Gulzar. Manjule’s Sairat (2016) directly engages with caste oppression and forbidden love, harkening back to Benegal’s masterpieces such as Ankur (1974) and Nishant (1975). Gulzar’s films, such as Talvar (2015) and Raazi (2018), demonstrate a blend of social critique and gripping narrative structures that resonates with Benegal’s approach to layered storytelling.

Transcending the urban-centric framework of Bollywood, Benegal emphasised regional and local stories and made the audience walk through the interiors of the country. His films, such as Manthan (1976), which was funded by farmers in Gujarat, and Susman (1987), which focused on the handloom industry, showed that regional stories could surmount their specific contexts to address global issues of economic exploitation and collective empowerment.

The impact could be observed in Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013) and Rima Das’s Village Rockstars (2017), which capture the cultural and socio-economic struggles of rural India, upholding Benegal’s commitment to grassroots storytelling and local authenticity.

Benegal’s integration of documentary aesthetics into narrative cinema also has had a lasting impact. Filmmakers like Anand Patwardhan (Jai Bhim Comrade, War and Peace) and Rakesh Sharma (Final Solution) directly extend Benegal’s legacy of combining realism with political engagement. The observational style and socio-political focus in their documentaries echo Benegal’s commitment to truth-telling and transformation through cinema.

Even fictional narratives, like Masaan (2015) by Neeraj Ghaywan, reflect the stylistic and thematic elements that Benegal popularised. The use of natural settings, minimalistic production design, and subtle character development continues to define the aesthetic of modern socially conscious cinema.

most read

Notably, the resurgence of issue-based cinema, addressing topics like LGBTQ+ rights, environmental degradation, and communal harmony, can be traced back to Benegal’s pioneering efforts to infuse activism into art. Filmmakers like Hansal Mehta and Onir carry forward Benegal’s humanist approach, focusing on the dignity and resilience of individuals challenging systemic injustices.

His demise marks the end of an era, but his legacy as a filmmaker, historian, and activist endures. His contributions to politically-engaged cinema remain a guiding force for filmmakers addressing questions of identity, justice, and representation. As long as cinema seeks truth and transformation, Benegal’s spirit will continue to inspire.

The writer is an Associate Professor in the Department of English Studies, Satyawati College, University of Delhi

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package