In the shadow of authoritarian rule, where the voice of dissent is often silenced, pockets of resistance find refuge in unexpected places. Coffee shops and informal addas emerge as vital sanctuaries for those who dare to challenge the status quo. The recent political war of words between Congress on the one hand and the BJP and the TDP on the other over the internationally recognised Araku Valley coffee, offers an opportunity to understand how coffee and adda culture have helped fuel dissent and revolution.

Coffee culture gained popularity in the 19th century, when the British began cultivating it in South India for export and local consumption. By the early 20th century, people from all walks of life were drinking coffee. However, like with every new trend, there was backlash, such as when a man from what was then Madras wrote to Gandhi, complaining that high-class Brahmin ladies were drinking coffee thrice a day, considering it fashionable. The issue was not so much coffee as the fact that women were drinking it. Despite this and other similar “complaints”, coffee’s popularity grew.

A new chapter in India’s romance with coffee began with the establishment of the first India Coffee House in September 1936 in Churchgate, Bombay. Driven by the Coffee Cess Committee, this initiative sparked a nationwide trend, leading to more coffee houses across the country. By the mid-1950s, these establishments faced an uncertain future. The Coffee Board of India, successor to the Cess Committee, considered closing them, threatening the livelihoods of hundreds of workers. A delegation, led by Communist leader A K Gopalan, sought Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s intervention. He suggested forming a cooperative society to manage the coffee houses, resulting in the Indian Coffee Workers’ Cooperative Society’s birth. By 1957, this cooperative opened its first coffee house in the Theatre Communication Building at Connaught Place, Delhi, marking a new era that ensured livelihoods and promoted Nehruvian socialism.

Eventually, this quaint place became a safe house for intellectuals and activists. The affordable prices attracted people from across the political spectrum. It was further fueled by Rammanohar Lohia’s vision of emulating German coffee houses as spaces for vibrant political debate. He brought credibility to the coffee shop culture, making it a hub for revolutionary ideas. One can say revolution needs coffee.

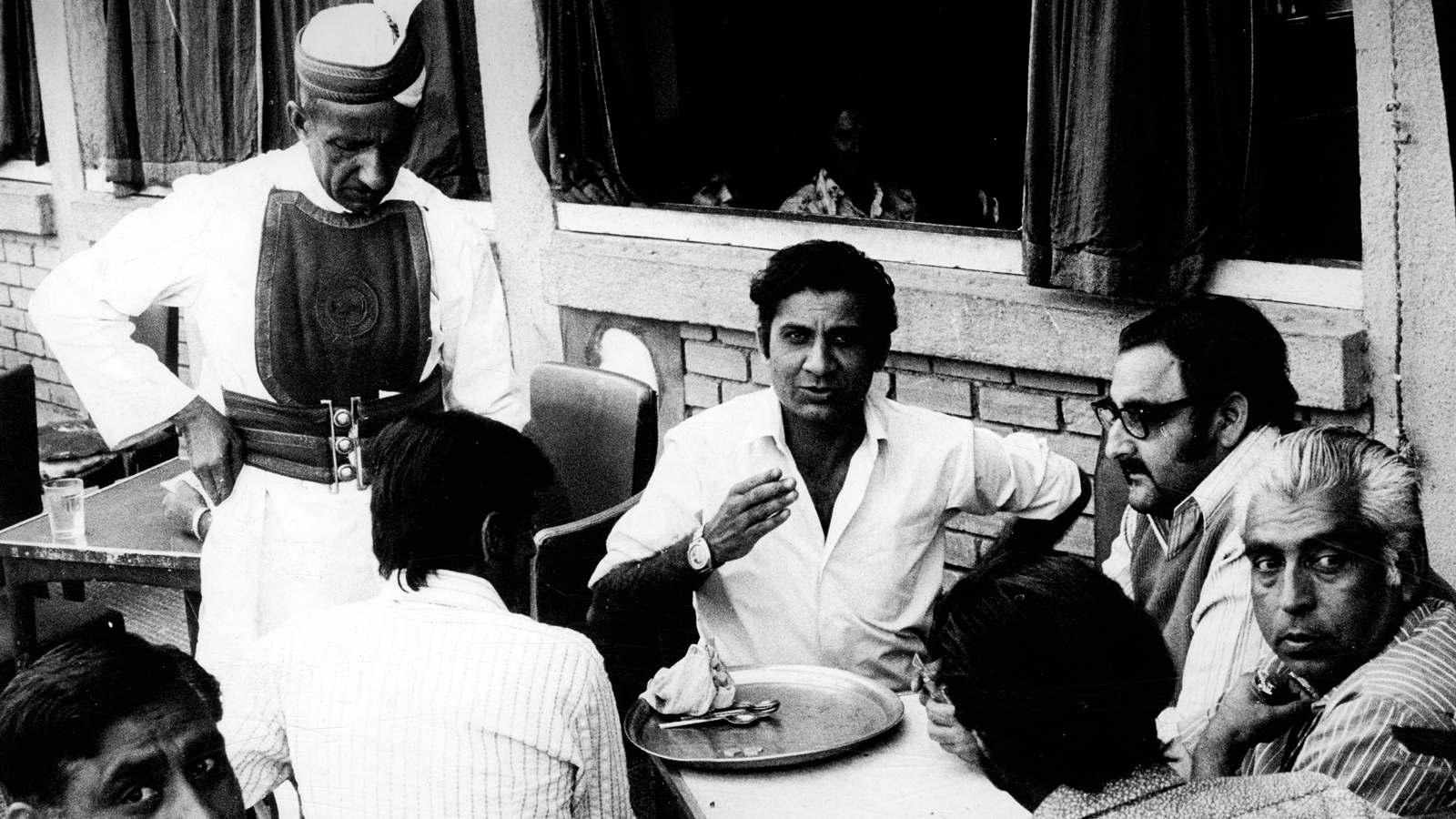

In Brewing Resistance: Indian Coffee House and the Emergency in Postcolonial India, author Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys describes the Indian Coffee House in Delhi as a hub of resistance during the Emergency. With just 35 paisa a cup, the coffee house became a space for free discussion, crucial during a time of repression and curtailed civil liberties. At Connaught Place, it emerged as a vital meeting place for students, political activists, intellectuals, and others to strategise their protests against the government. These clandestine meetings were held in hushed tones amidst the clatter of cups, the aroma of coffee and cutlets.

The Indian Coffee House also served as an unofficial news centre. With mainstream media heavily censored, information spread through word of mouth, pamphlets, and foreign radio broadcasts like the BBC. This was essential for keeping the spirit of resistance alive. The coffee house became a venue for organising protests, recruiting volunteers, and formulating strategies for underground movements.

However, the sanctuary of the Indian Coffee House was not immune to the state’s attempts to quash dissent. On May 15, 1976, without prior notice, officials from the New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC), ordered the workers to vacate the premises. By noon, the building was demolished. This event was a blow to the resistance movement. Many regular patrons felt a profound sense of loss. The demolition of the coffee house was more than the destruction of a building; it was an attempt to dismantle a critical space of political and intellectual engagement. While the official explanation cited the dilapidated condition of the building, many believed that the real motive was to stifle the growing dissent nurtured within its walls.

One of the most significant aspects of the Indian Coffee House was its role in fostering alliances between different political groups. Despite their ideological differences, Socialists, Communists, and even some members of the Janata Party found common ground in their opposition to the Emergency. These alliances were crucial in organising a unified front against the government. The coffee house provided a neutral ground. This sense of solidarity and collective action was instrumental in the eventual lifting of the Emergency and the restoration of democracy in India.

In the same book, Plys quotes P Singh, a Communist, as saying, “The coffee house was where opinions were formed. For democracy, the coffee house is essential.” In the 1980s, there was a regular table for queer activists, where people met to share personal stories, seek support, and discuss sexuality and politics. During the recent CAA protests and the farmers’ protest in Delhi too, I recall seeing many activists gathering at various coffee shops, including the Indian Coffee House, which remains a democratic space and symbol of revolution.

Hussain is a chef and author