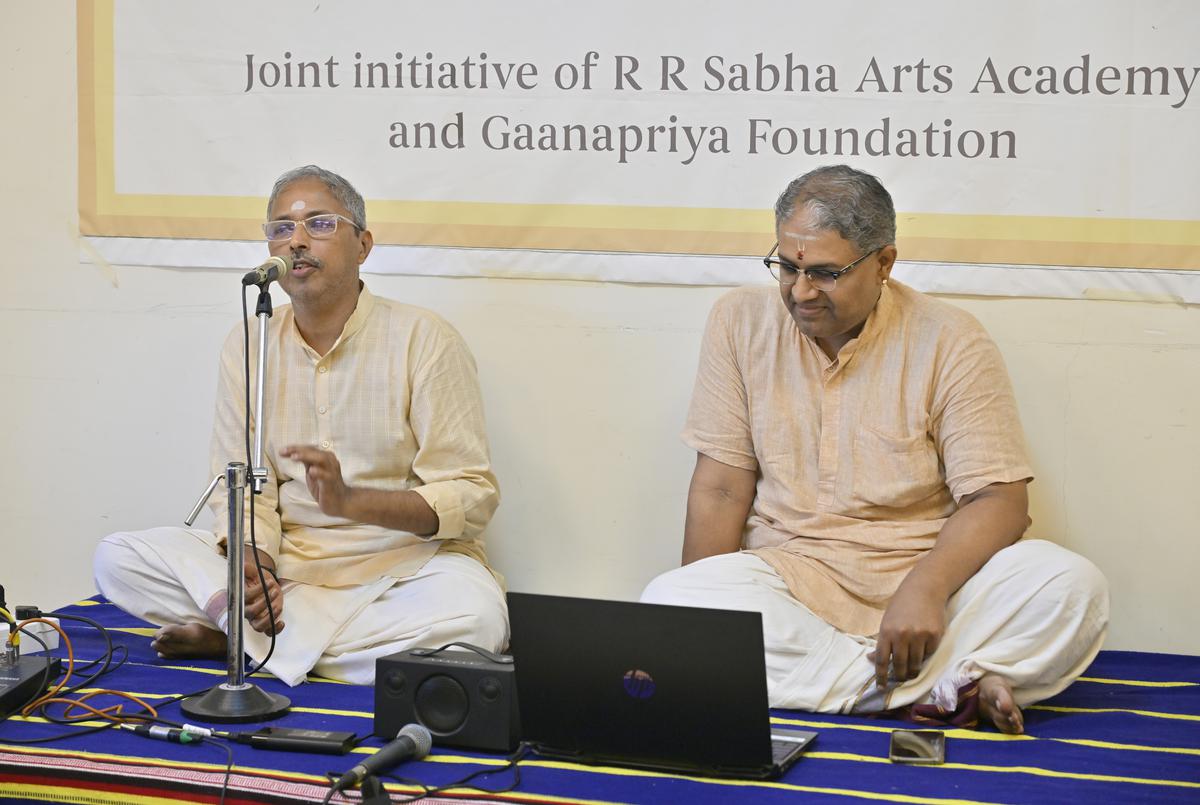

Composer-mridangist K. Arunprakash during the Palani Subramania Pillai’s listening session at R.R. Sabha, Mylapore. | Photo Credit: Akhila Easwaran

Quite a lot has been spoken about mridangam legend Palani Subramania Pillai as his 115th birth anniversary was celebrated last April. Musicians have enthusiastically recalled how Subramania Pillai’s mridangam accompaniment blended seamlessly with the music. This effect mesmerised certain star vocalists such as Madurai Mani Iyer, who once while singing Tyagaraja’s ‘Enduku peddala’ stopped midway during the niraval at the phrase ‘Veda shastra’ just to listen to Subramania Pillai’s playing. This was a heart-warming display of mutual admiration between the vocalist and percussionist.

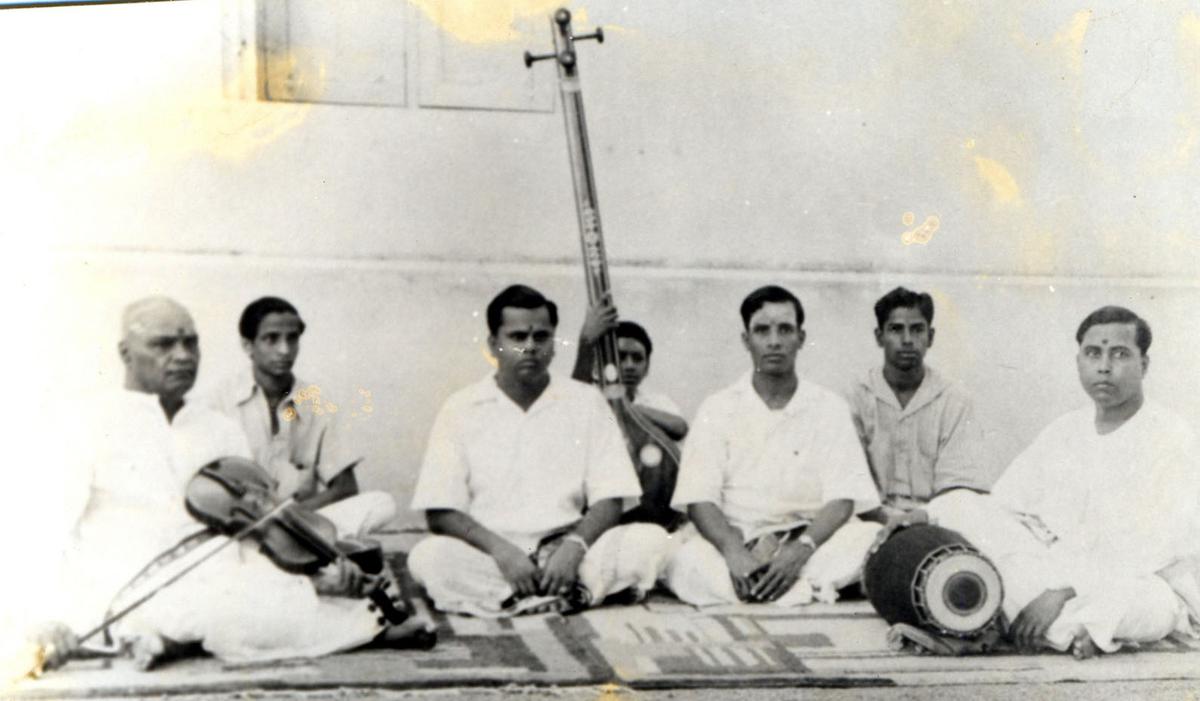

The young Palani Subramania Pillai. Photo: | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

In a listening session organised by Gaanapriya Foundation in association with Rasika Ranjani Sabha, ace mridangam player K. Arun Prakash took listeners through several rare recordings of yesteryear masters to decipher and re-experience the Palani magic. Arun, who hails from the Palani School through his guru Ramanathapuram M.N. Kandaswami, conducted the session with much finesse as his approach was experiential and straightforward.

Band together

When listening to Musiri Subramania Iyer singing the kriti ‘Amba nadu vinnapamu’, one could hear Subramania Pillai’s mridangam becoming one with the music. Arun chose to categorise this as a musical mridangam experience — the mridangam completely entered the zone of Todi, showing how much knowledge of music Subramania Pillai possessed, to submerge himself with the vocalist and violinist. Palani Subramania Pillai was hailed as a ‘tyagi’ (someone who sacrifices themselves) by Madurai Mani Iyer because he would never highlight himself when accompanying other musicians. In the olden days, this was traditionally defined as ‘pakka vadhya dharma’.

Arun Prakash elaborated that Subramania Pillai had to balance his virtuosity with the music being sung to optimally bring out the best aesthetic experience. As a mridangam player, who regularly inserted complex patterns almost spontaneously, Subramania Pillai’s sollus were traditionally handed down to him. Being one of the few left-handed mridangam players of his generation, Subramania Pillai’s journey was not easy as he had to prove himself as a worthy accompanist. He never gave up despite facing rejection and many other obstacles in his career.

Composer-mridangist K. Arunprakash elaborated how Subramania Pillai had to balance his virtuosity with the music being sung to optimally bring out the best aesthetic experience. Carnatic Vocalist Navaneet Krishnan looks on. | Photo Credit: Akhila Easwaran

Continuity is an important concept when playing the mridangam on stage. As the vocalist progresses, sangati by sangati, the mridangam artiste needs to sail along uninterruptedly. However, Subramania Pillai demonstrated that even silence maintained continuity.

Significant pauses

Arun Prakash excellently observed that Subramania Pillai’s mridangam expressed itself louder during the pauses, accruing significance and depth to the music by toning itself down gracefully. This can also be called ‘going with the laya of the music’ as the mridangam never overpowered the vocalist but instead added a layer of sound to the grand tapestry of music visualised by the vocalist.

Alathur Brothers with Rajamanikkam Pillai and Palani Subramania Pillai. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Arun Prakash also pointed out that maintaining the kaalapramana is a lost art today as the percussionists who accompany vocalists invariably tend to alter the speed in many kutcheris. Kaalapramanam adherence was one of Palani Subramania Pillai’s hallmark qualities that distinguished himself from other yesteryear mridangam artistes.

Some argue that mridangam players then hesitated to offer turns to upa pakkavadhya artistes such as ghatam and kanjira. Arun Prakash felt that this was not the case always, as Subramania Pillai often worked well with the ghatam vidwan on stage, to ensure that they took turns meaningfully. After all, Subramania Pillai himself was a kanjira player too. Variety in sound was ensured for the rasikas when the mridangam was reintroduced after the ghatam, as a listener-friendly approach was prioritised. Perhaps rasikas keenly followed these transitions. Today, rasikas mostly zone out and hardly have the time or interest to take note of these subtle arrangements between percussionists.

Another interesting recording sourced by Arun Prakash was that of Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer singing a four-hour wedding concert at Kallidaikurichi in 1958 accompanied by Subramania Pillai and 28-year old T. N. Krishnan on the violin. Semmangudi and TNK dished out several avartanas of swaras in ‘Marivere’ (Anandabhairavi, Syama Sastri) with Subramania Pillai playing along melodiously. It was surprising to note that only two mics were used in the kutcheri and they were reserved for the vocalist and the violinist. Even without a dedicated mic, Subramania Pillai’s mridangam stood out as he knew how to balance the sound even with these constraints.

Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer with Palani Subramania Pillai and Mayavaram Govindaraja Pillai as accompanists at a concert for Kalaniketan. | Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Using a recording of Musiri Subramania Iyer’s ‘Brovavamma’ in Manji, Arun Prakash explained how Subramania Pillai never approached the piece as just another Misra Chapu kriti but gave much importance to the overall mood of the song, merging the sound of the mridangam with the bhava of the kriti. It was interesting to note that Subramania Pillai’s arudis usually finished with the song itself, as he was not one to indulge in lengthy theermanams. This meant the vocalist had to know that the next stanza must be commenced by them on their own, requiring them to be extra alert.

Complex rhythmic patterns

Even during tani avartanams it was easy for vocalists to miss out on the tala while listening to Subramania Pillai, as he often displayed his intellectualism through complex rhythmic patterns and intricate arithmetic combinations.

Listening sessions such as these are valuable for rasikas to grasp the grandeur of vintage music. Even though there is no dearth of talent today, it is undeniable that the music of yesteryear musicians was unique and possessed admirable aesthetic qualities that are rarely seen now.

Rasika Ranjani Sabha’s efforts aimed at music appreciation need to be encouraged by rasikas and musicians by attending in large numbers.