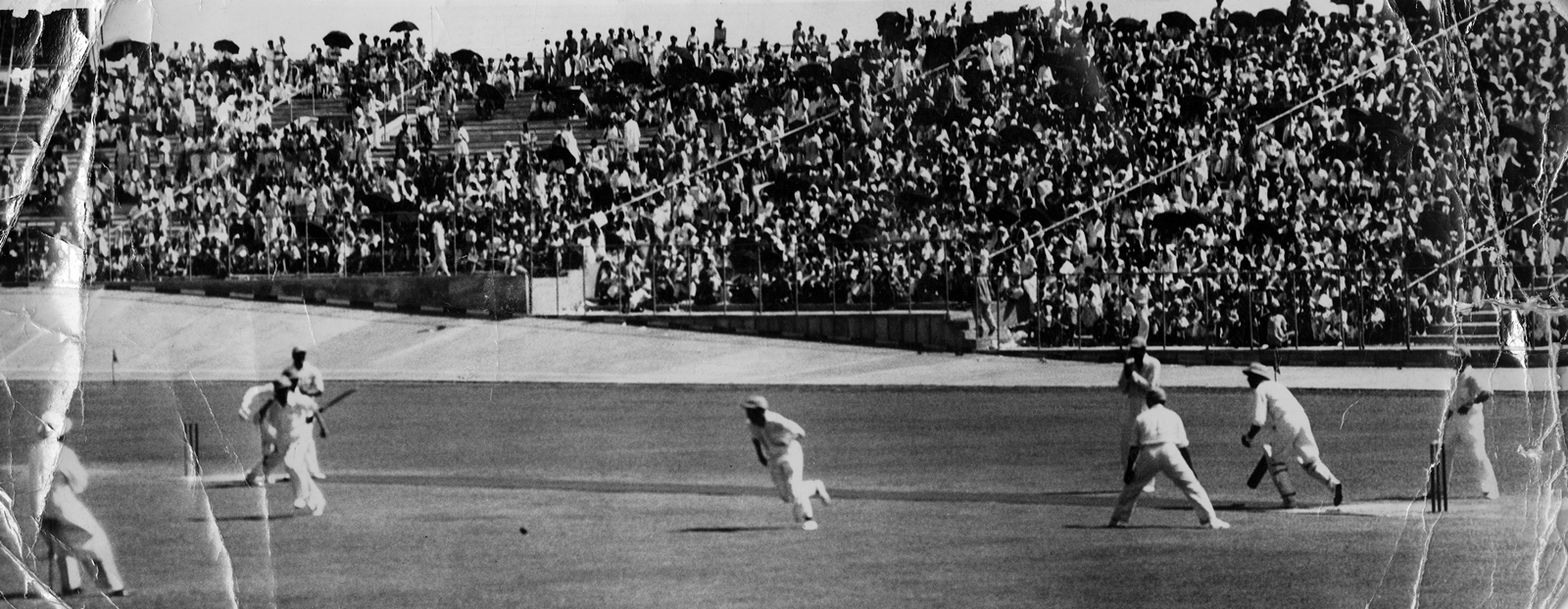

With the 27th meeting of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Movement (CHOGM) just completed in Apia, the capital of Samoa, and with the Indian cricket team licking its wounds after being beaten by New Zealand in the recent Test series, it is relevant to look back 75 years ago, when the Commonwealth movement and Indian Test cricket almost collided.

The Imperial Cricket Conference (now the International Cricket Council) was formed in 1909 with England, Australia and South Africa as the three founder-members. While the first two had played the first official Test match at Melbourne in March 1877, South Africa had been granted Test status a few years later and played their first Test series at home against England in 1888-89.

The standard of cricket in South Africa at the time was barely that of an English county second XI. Yet they got membership over more deserving candidates, particularly the US and Argentina where cricket was much stronger (purely due to their being a member of the Commonwealth). This was one of the main clauses of the ICC: Only members of the Commonwealth would be allowed membership.

India played its inaugural Test as a member of the ICC at Lord’s in 1932 when still under British rule. It played its first series as an independent nation in Australia in 1947-48, and first at home with West Indies in 1948-49.

A piquant situation arose in 1950 when after becoming a republic, the government was considering leaving the Commonwealth altogether, which, in turn, would have meant India losing membership in the ICC and its Test status.

But despite pressure from Home Minister Sardar Vallabhai Patel and his own ruling Congress party, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to stay within the Commonwealth fold.

At the annual meeting at Lord’s, London, in 1948, even while the debate was raging in India whether to stay or leave the Commonwealth, the ICC, for its part, deferred a decision on India’s membership for two years and granted it provisional status.

India became a Republic on January 26, 1950, but thanks to Nehru remained part of the Commonwealth. This meant that at its 1950 ICC meeting, India was granted permanent membership.

Nehru had played cricket while at school in Harrow and would regularly turn out for the annual parliamentarians’ match in Delhi. Whether or not his decision was partly motivated by a desire for India to retain the Test status is not known. But in effect he did save cricket in India at a time when it was competing for attention with football and hockey. Being stripped of the Test status so soon after Independence would surely have sounded the death knell for the game in the country.

This incident was narrated by Mihir Bose in his 2019 book The Nine Waves: The Extraordinary History of Indian Cricket.

However, there was another twist to the story. Just over a decade later another piquant political situation arose which sorely tested the ICC. South Africa, under the threat of sanctions from member nations due to its racist Apartheid policy, decided to unilaterally withdraw from the Commonwealth under hard-line Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd.

This meant automatic suspension from the ICC. It had been founded largely on the initiative of the South African gold and diamond tycoon Sir Abe Bailey, with Clause 5 of its constitution implicitly intended to exclude the powerful American team.

This came back to bite South Africa. At the 1961 ICC meeting at Lord’s, a decision on the vexed issue was deferred till the next year. And in 1962, the decision was: There was nothing preventing matches played by South Africa from being called Tests, though these were not recognised as official by the ICC. This only added to the confusion.

In essence, the whole issue was brushed under the carpet with South Africa continuing to play against England, New Zealand and Australia alone, as had been their practice. Despite the mixed signals about the status of their matches — official or unofficial — all cricket statistical records have gone with the former.

With England and Australia having the veto, the non-white members — Pakistan, South Africa and West Indies — had little say in the matter.

But South Africa was eventually banned from all international cricket in 1970 as well from the International Olympic Committee and other world sporting bodies due to pressure from the non-White bloc. It made a return to world cricket only in November 1991 with a historic tour of India consisting of three One Day Internationals. This, after the unbanning of the African National Congress and the release in 1990 of its iconic leader Nelson Mandela after 27 years of imprisonment.

A lot has changed in world cricket over the past 75 years. The veto power of England and Australia was abolished soon after Jagmohan Dalmiya became ICC President in 1997. The ICC’s membership now extends to over 100 countries worldwide. Today, with its enormous financial clout, thanks largely to the cash-rich Indian Premier League, launched in 2008, it is India that calls the shots in international cricket. All thanks to India’s first Prime Minister, however inadvertently.

The writer is the author of numerous sports books including his latest, Salim Durani: The Prince of Indian Cricket