Like many of us, I was introduced to Shakespeare in my school. But it was more of a chapter in a book to be read and written in an exam, than to be actually grasped. It was not only because of their matured themes, but also the complexity and toughness of their language,” shares Vishal Bhardwaj, reiterating the ‘highbrow’ view of the Bard in pop culture today.

However, in his own time, Shakespeare was anything but highbrow. From

Maqbool

to

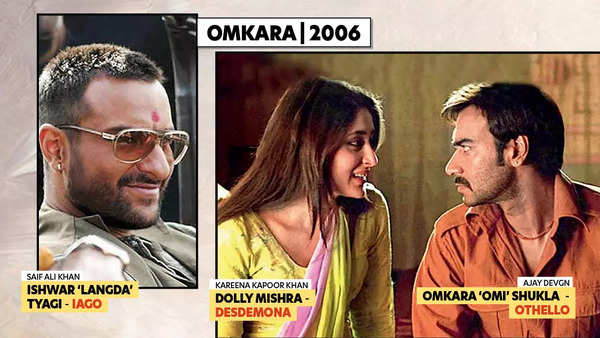

Omkara

and

Haider

, Bhardwaj’s adaptations of the Bard’s classics has been a study in Shakespeare’s genius – replete with pure theatre, drama and sentiment.

‘Maqbool’s adaption was an accident’

My first film in the Shakespeare trilogy, Maqbool, an adaptation of Macbeth, was accidental. I was on a train, on the way back from my godson’s boarding school, and happened to chance upon it in the form of a short story in his schoolbook. Back then, I was searching for a story which could be based in the backdrop of the underworld, and I found Macbeth to be a perfect fit for it. It was only after that did I read all the other works of Shakespeare. Not only are they timeless, but also human in a way which can be moulded into any culture or setting. The human traits remain the same, making Shakespeare’s characters contemporary and relevant throughout the world.

‘Iago is one of the best negative characters written by the Bard’

Othello was Shakespeare’s second play that I adapted. Naseer Bhai (Naseeruddin Shah), whom I look up to him for creative validation, was of the opinion that Othello was Shakespeare’s weakest play. But I was very fascinated by the character of Iago, who ultimately becomes the weaver of the protagonist’s tragic arc. To me Iago is one of the best negative characters written by the Bard. I wrote my script and presented it to Naseer bhai, who loved my adaptation and gave me a go-ahead. And that’s how Shakespeare’s Othello became my Omkara.

‘Kashmir, like Hamlet, was in a similar state of affairs – to be or not to be’

After that, it took me eight years to complete the trilogy. There were so many plays and the myriad of ways in which they could be adapted that the process took such a long time. Finally, the only competition left was between King Lear, Julius Caesar and Hamlet. I decided to go with Hamlet, which became the third entry in my trilogy in the form of Haider. Hamlet offered an unusual complexity and I found the characters more fascinating for me to explore. The characters of Hamlet are unlike any other seen, yet had familiar angst. The mother, the uncle, the father, the ghost, the relationships they shared with each other had their own intricacies. They’re deeply layered and dark. Once I found its backdrop in Kashmir, I got even more excited. Kashmir, like Hamlet, was in a similar state of affairs. Like Hamlet, it asked – “to be, or not to be.”

How Bharadwaj’s films moulded the three tragedies

Former President of the

Shakespeare Society of India

Professor Jonathan Gil Harris, talks about Bhardwaj’s oeuvre, highlighting how the films mold the plays. Talking about Maqbool, he says, “Bhardwaj’s Maqbool, set in the Mumbai criminal underworld, injects an element of Bollywood masala into Shakespeare’s story: its title character murders his gang boss not just to gain power, but also to satisfy his forbidden love for his boss’s mistress. Maqbool is less of a monster than a broken Romeo.” Likewise, in Omkara, “the film lets Indu, Langda’s wife, have the last word: she kills her husband in revenge,” and in Haider, the question, to be or not to be, that Hamlet famously asks, “becomes a question of a people longing for freedom: ‘hum hain ki hum nahin.’”