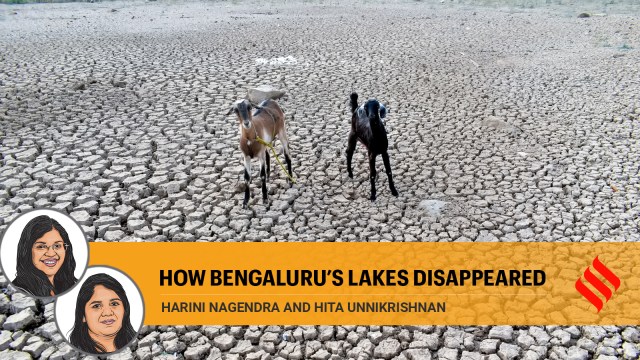

Once again, the summer of 2024 finds Bengaluru in the grip of an acute water crisis, accompanied by intense, relentless heat. Some estimates even say the city will run out of water by 2025. Yet, the city is no stranger to water scarcity, as older residents of the city will remember. Because of its position within the rain shadow of the Deccan Hills, and the fact that no major river flows directly through it, the city is geographically prone to water scarcity. Over the decades and centuries, there has been a drastic shift in the city’s relationship to water.

Early settlers worked with the natural lay of the land to conserve natural resources in precolonial and early colonial times. Later, during the late colonial period, the city moved towards a reliance on large technocratic solutions, modifying and reshaping nature to suit the needs of the city.

Built to sustain a largely agrarian economy, the city’s tanks (now called lakes) date back to well before the 9th century CE. They were engineered by making use of the natural elevation gradient of the city. Natural depressions within the landscape were connected by means of stormwater channels, allowing water to flow from one lake into the next. Shallow aquifers recharged by these lakes provided a secondary source of water, accessed in the form of large community managed open wells, especially during the drier months of the year.

These tanks were managed as commons, supporting irrigation, fishing, farming and pottery. More intangibly, they also supported the cultural and spiritual practices of communities dependent upon them. Lakes and their associated wetlands were critical biodiversity refuges and were important in flood control — acting as sponges in the monsoon to soak up excess water — and in drought relief in the summer, releasing the excess ground water via open wells.

After 1799, British rule in the region transformed the governance of the city’s waterscape. From collective ownership, lakes came under state control. Their association with livelihoods began to dwindle, along with their sacred and cultural importance, and they began to be viewed as recreational accessories to the city. Especially in the British dominated Cantonment, lakes were appreciated primarily for their aesthetic and recreational values. As the city grew, they also became receptacles and conduits for sewage, leading to outbreaks of cholera and other epidemics, resulting in the perception of open water bodies being unsanitary and unhygienic.

By 1892, after a succession of low rainfall years, piped water was introduced to Bengaluru, transported from the Arkavathy basin. After this, the importance of lakes rapidly dwindled. Many lakes and their associated stormwater channels were filled over to make way for the construction of bus stadiums, residential layouts, malls and sports stadiums.

Our research has shown how the death of one lake, Dharmambudhi (now the Majestic bus stand), led to the decline of an entire sub-system of waterbodies connected by this stormwater channel network. We have also documented the loss of open wells — from about 1,800 wells in the city centre in 1885 to less than 50 wells by 2014, of which only a fraction were functional. The loss of the wetlands and grasslands around the lakes that also served as ground water recharge sites has also impacted the city, collectively leading to seasonal crises of flash floods and droughts in the very areas where lakes and wetlands once thrived.

In an era of looming climate change, what does this mean for the resilience of dry Bengaluru? It is challenging to revive the old network in the heart of the city, some of which have been lost for well over 50 years. However, the lakes in the periphery of the city can still be restored, along with their wetlands. From an ecological standpoint, they sustain critical biodiversity and function as lung spaces for a rapidly growing city. From a social standpoint, they continue to sustain lives, livelihoods and cultures and remain integral to the most vulnerable people in the city. From the perspective of water resilience, they continue to hold relevance as secondary water resources for the city – one that can enhance the long-term water security of the landscape, together with other forms of sustainable water management and use such as practices of rainwater harvesting or recycling grey water for purposes such as washing, cleaning, gardening, or irrigation.

Bengaluru was once a kalyananagara, a city of lakes that functioned as the community centre of local neighbourhoods, critical for local economies, sacred cosmologies, biodiversity and human wellbeing. We need to recover this lost imagination of Bengaluru, to re-imagine it once again as a city of water, for the resilience of the city — as well as the many millions who call this city home.

Hita Unnikrishnan is Research Associate at The Urban Institute of The University of Sheffield

Harini Nagendra is Director and Professor, Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability, Azim Premji University