The Lok Sabha elections are in full swing. The third voting phase, scheduled for May 7, is a crucial milestone. This phase will witness all 26 seats in Gujarat and the remaining half of 14 seats in Karnataka going to polls. Once this phase concludes, voters will have exercised their franchise for more than half of the 543 seats in the Lok Sabha. After that, the election momentum will shift to Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, where voting for all the seats will occur on May 13.

How all Indians got a vote

The history of elections in our country has multiple starting points. One of them is the discussion about every adult’s right to vote. Colonial administrators decided that an illiterate electorate, the absence of political organisations and the burden on the official machinery made adult franchise impracticable. After Independence, our Constitution framers discussed the issue at length. There was scepticism because of illiteracy, but there was also the belief that a limited franchise would be “a negation of the principles of democracy.” They decided that adult suffrage should be the basis of elections to Lok Sabha and state legislative assemblies.

While these deliberations were ongoing, the Constitution Assembly Secretariat began preparing a draft electoral roll in 1947. Ornit Shani, in her wonderfully written book, How India Became Democratic, details the meticulous process followed by the secretariat. In the introduction, she states, “Making the draft electoral roll on the basis of universal franchise in the context of the unfolding grim tragedy of partition, ultimately enrolling 49% of India’s population, the vast majority of whom were poor and illiterate, in anticipation of the constitution, required a rich political imagination.”

In 1950, the Election Commission (EC) took over the work done by the Constitution Assembly Secretariat. Passing the appropriate legislation, election preparedness of states, and environmental factors like floods in Bihar delayed the first elections. In November that year, President Rajendra Prasad informed the members of the Provisional Parliament that General Elections would take place in November-December 1951.

Wood, steel and hiccups

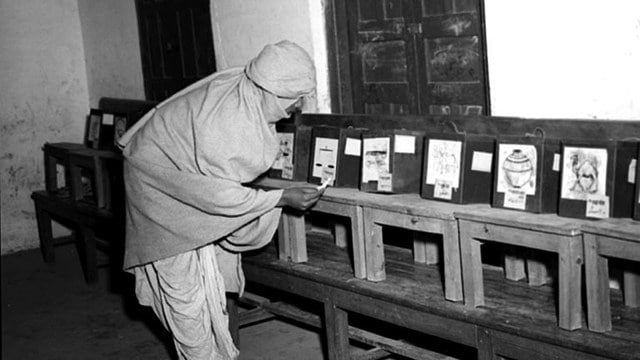

During this time, the EC was also busy finalising the details of the actual voting process. It adopted the polling process suggested by the Indian Franchise Committee of 1932 (which recommended against adult franchise). This committee suggested that there should be a separate ballot box with a distinctive colour/symbol assigned for each candidate. The committee provided a simple mechanism for allocating colour/symbols to candidates and the location and design of polling stations. It noted that a pair of polling clerks should not handle more than 1,000 voters.

To ensure standardisation in the voting process, the EC prescribed the shape and specifications for the ballot box. One requirement was that the slit on the top of the box should allow the insertion of a ballot paper of the size of a rupee note. It also specified that the manufacturers were to use 20 gauge steel for making the boxes. The EC estimated that holding the first general elections to Parliament and state assemblies would require roughly 19 lakh steel ballot boxes. Manufacturing these would have required 6,000 tons of steel. To put that number in context, the iron weight in the Eiffel Tower is 7,300 tons.

The EC then approved designs by multiple manufacturers across the country. Three significant ones were Godrej and Boyce Manufacturing from Mumbai, Allwyn Metal Works of Hyderabad, and Bungo Steel Furniture based out of Calcutta. The Godrej-designed ballot boxes had a unique locking mechanism that ensured no one could tamper with them without breaking a seal. They secured most of the ballot box orders. In its contract with Bihar, Godrej offered to donate the difference between their and a competitor’s price to the state government.

But things did not go smoothly in some of the other cases. In the box made by Allwyn Metal Works, the slit for inserting the ballot paper was smaller. The company had the impression that the ballot paper, which was the size of a one-rupee note, could be folded before being inserted into the box. EC approved their design, and they manufactured thousands of boxes. When EC noticed the anomaly, it ordered the ballot paper to be cut to a smaller size. Bungo Steel Furniture did not produce adequate ballot boxes for different states. As a result, Madras became the only state that used steel and wooden ballot boxes, the wooden ones made by prisoners.

Securing the vote

EC came up with detailed guidelines for ensuring the security of ballot boxes. It also introduced marking voter fingers with indelible ink to prevent impersonation. By the second general election in 1957, the EC had shifted from separate ballot boxes for each candidate to one box for all candidates. It also publicly addressed concerns about the ballot boxes’ tamper-proof nature. However, with increasing muscle power in elections, in certain parts of the country, booth capturing and stuffing ballot boxes became a regular affair. The EC responded by making booth capturing a crime and then shifted to the Electronic Voting Machines.

The humble ballot box is no longer part of the general election process. The EC now uses it for elections to the office of President, Vice President and Rajya Sabha. While the ballot box may be history, the principles from that era are still in use during the general elections in the country.

The writer looks at issues through a legislative lens and works at PRS Legislative Research