If Che Guevara can be on a t-shirt, why can’t Gandhi be used to sell facial cleansers?” It’s a fair question, asked after a knee-jerk reaction — an instant revulsion — to the “one-day exclusive offer” from an overpriced beauty products company on October 2. (This place sells “forest essentials” like “age-defying” sunscreen — in a rather diminutive bottle at that — for Rs 6,495.) A cursory Google search will throw up many a Gandhi Jayanti offer, and with the exception, perhaps, of the one by government-run Khadi stores, they all leave a bad aftertaste.

The question, though, is why.

Mothers and fathers, lovers and friends, even dogs and cats — every relationship now has a “day” since the days of Archies stores, every emotional bond a discount and a package deal for its expression. The attire of politicians is branded by their name and sold at high-end stores at airports. Entire supply-and-logistics chains are set up to ensure same-day delivery for the consumer by companies like Amazon, arguably at the expense of the worker. “Fast fashion” makes clothes cheaper than ever, climate change and poor working conditions be damned.

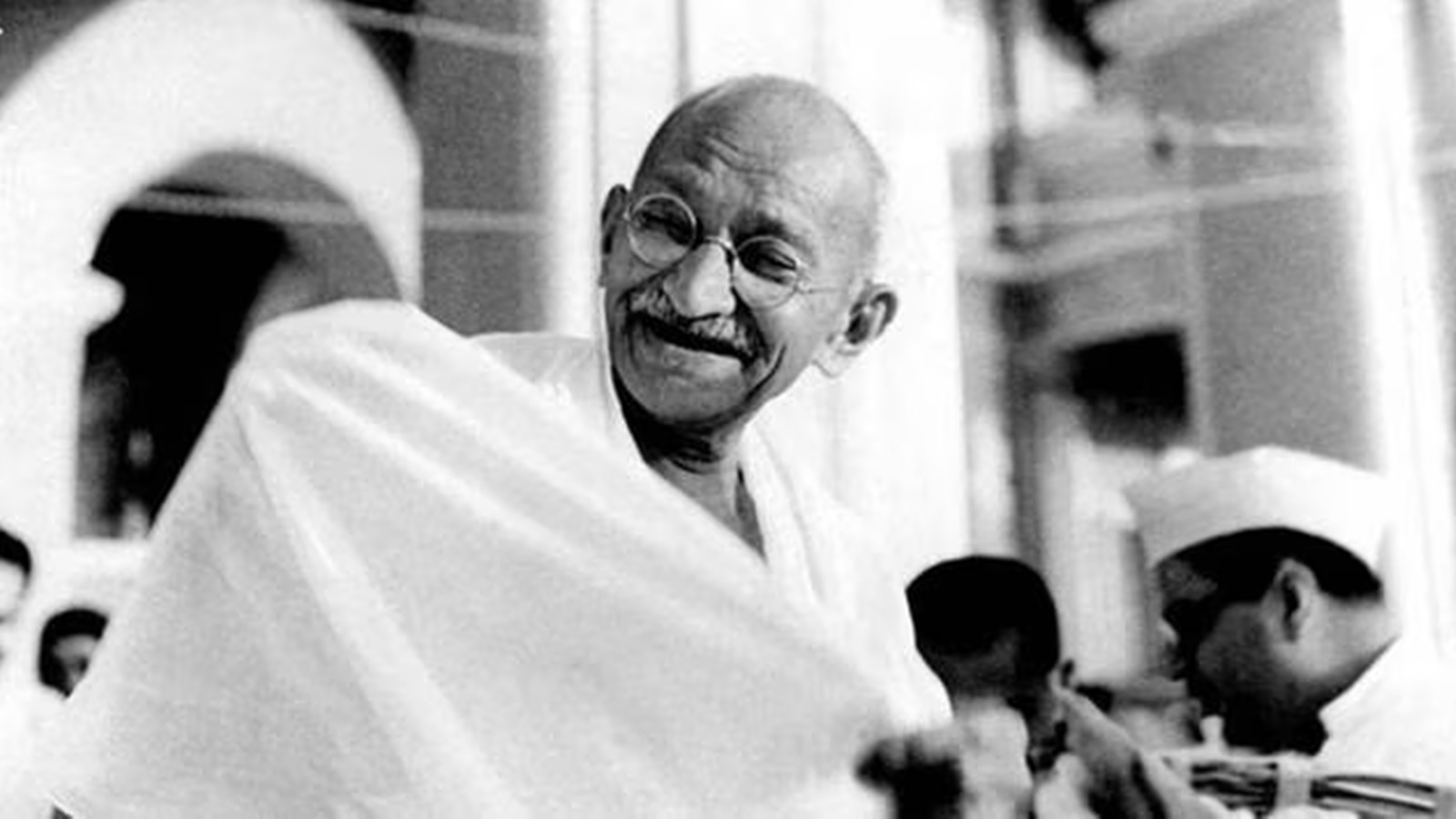

Why, in all of this, should Mahatma Gandhi be so hallowed? Or for that matter, any “great” man? In the age when anyone can become an “influencer”, when there is democratisation of both celebrity and brand endorsers, what could be more egalitarian than taking the birthday of the man on the currency note and using it to sell t-shirts and beauty creams? The producer (more accurately, the malik) sells more, the consumer pays less. Win-win.

Except, of course, it’s not. And it is in three of Gandhi’s most well-known principles that the answer to the “why” of our discomfort can be found.

First, Gandhi did not believe in the moral escapism of consumers getting the “best deal”. The entire reason he began spinning his own cloth was to undermine the exploitative economic system of the British Raj which impoverished the Indian farmer and British textile worker, while enriching a few. For him, all of us were not mere consumers but moral agents. How and what we bought could not be a blind act of self-interest. This is not to say he was Marxist. Unlike scientific socialists, he genuinely believed in the power of individual morality to alter social and economic structures.

In fact, long before Greta Thunberg, he showed the world that it is only by altering lifestyles that we can build a sustainable society.

Second, Gandhi believed in truth above all else. Contemporary marketing and advertising — whether by governments or private players — on the other hand, is based on selective appropriation and, for want of a better word, subterfuge. Will an anti-ageing serum really turn back the clock? Or, for that matter, was Coronil ever really an effective treatment against Covid-19? Gandhi was not averse to business. He did, however, believe in a trusteeship model, where those who owned the means of production were trustees of the common good. A discount, by definition, is a violation. It is an admission that, more often than not, companies charge more than a reasonable margin to increase their profits.

That is, of course, the essence of the economic system we live in. But surely, we can keep Gandhi out of it — at least on his birthday.

Finally, and most importantly, is the question of means and ends. Simply put, violent means cannot produce peaceful or desirable ends. In that sense, the father of the nation was on the opposite end of the spectrum as Benjamin Netanyahu, as well as Steve Jobs and Tim Cook. He would not, for example, want his name associated with products that exploit labour in certain countries so that those who can afford it across the world can get another iPhone to numb themselves with reels. He would likely think that a “forest essential” is not a beauty product but rather, the lives and livelihoods of those who depend on it.

Of course, Che Guevara wouldn’t have wanted to be on a t-shirt either. And in the face of a complimentary “Gandhi Jayanti Self-Care Kit”, and discounts on watches, shoes and clothes, what’s a little moral bankruptcy?

aakash.joshi@expressindia.com