A rare sight was witnessed at an Amaravati rally— an Indian politician speaking about women’s unpaid labour at home and the cycle of caregiving. “Khana bhojan banati hain, bachcho ke dekhbhaal karti hain. Hindustan ke bhavishya ki raksha karti hain,” Congress leader Rahul Gandhi said on April 25.

Also Read: Lok Sabha polls 2024 LIVE- April 30

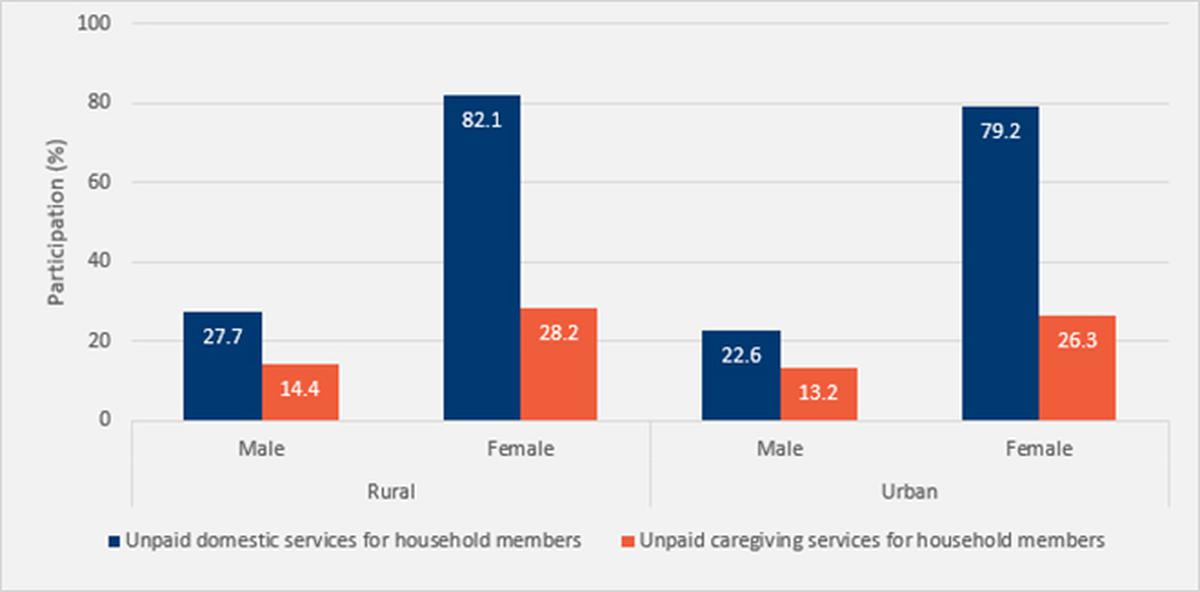

Mr. Gandhi’s comment spotlighted a reality: women spend eight to 10 times more time on unpaid care work than men. Every woman works a double shift, according to the Time Use Survey 2019: eight hours of paid labour outside, another eight within households. Their second shift is time spent cooking, looking after children, and safeguarding the future of India. Still, their caregiving at home is not economically valued, and “no government compensates them for this labour.”

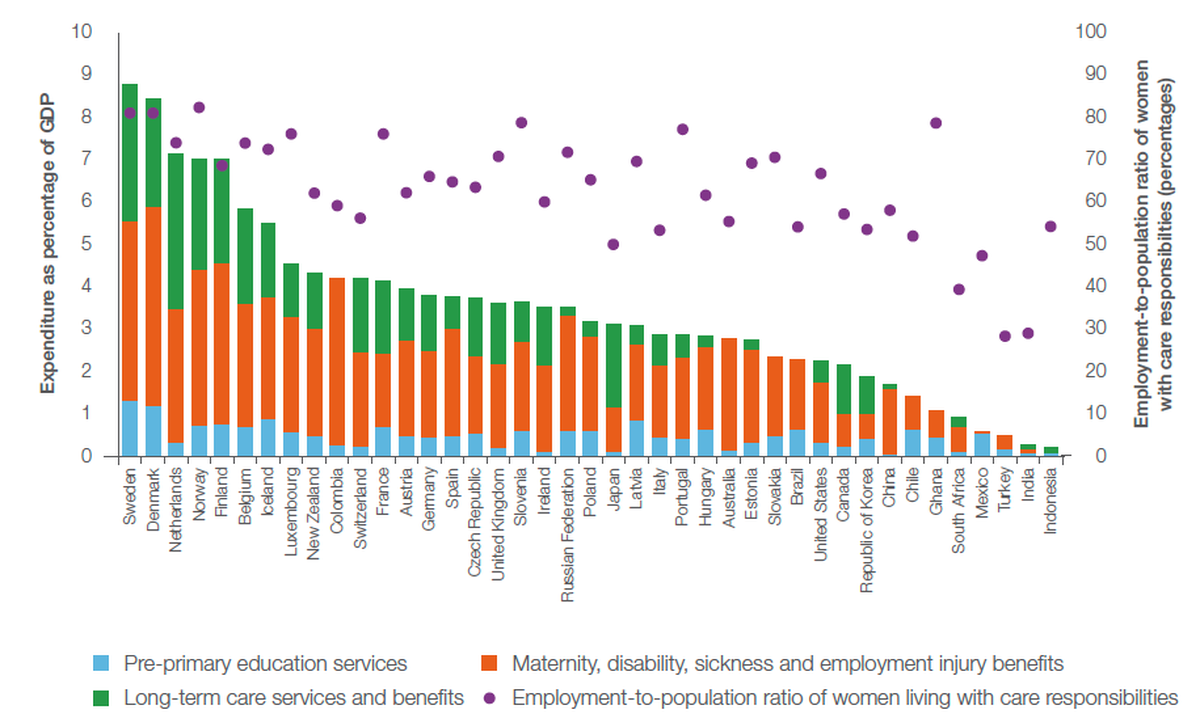

The care economy is ubiquitous and undervalued. The web is spun by people, mostly women, partaking in paid and, more frequently, unpaid labour; their responsibilities branch into childcare, domestic chores and elder care. This caregiving reproduces the labour force, replenishes welfare and contributes 7.5% to the GDP. But for women, it gives way to a ‘time poverty,’ reducing the time they can dedicate to paid work or to acquire skills for better jobs. If well-funded, this sector can generate more than 11 million jobs by the end of this decade; 70% of which will go to women, according to a recent report. India, however, spends less than 1% of its GDP on the care economy, reinforcing a system where caregiving is underestimated and underpaid.

There is no proper enumeration or identification of care economy workers in India. The sector includes home makers, Anganwadi workers and ASHAs, domestic workers, social workers, teachers, registered nurses, and doctors, among others, “involved in meeting the physical, psychological and emotional needs of adults and children, old and young, frail and able-bodied,” per the International Labour Organisation. The Hindu sorts through a surfeit of economic promises to see how, and if, the care economy finds mention in the present electoral landscape.

About unpaid labour of homemakers

Parties do not mention care givers but promise cash transfers and amenities, such as clean fuel or water supply, that can aid women. Congress’s election manifesto pledges to transfer ₹1 lakh annually to the bank accounts of the oldest female member in the house, for households belonging to economically disadvantaged communities. The Bharatiya Janata Party, on the other hand, promises to expand the Lakhpati Didi scheme — providing interest-free loans to women and offering training — to enable women to earn an income of a similar amount. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and AIADMK have also assured a monthly entitlement of ₹1,000 and ₹3,000 to women respectively.

Other welfare policies have been not pitched as compensations explicitly for the unpaid labour of women. BJP has promised free rations and free electricity; Congress pledges to devise a nationwide plan to provide potable water and inclusion of pulses and cooking via the Public Distribution System (PDS). The DMK has proposed a cap on fuel prices, and CPI(M) has suggested a universalisation of the PDS.

Pledges on health do not mention women or care givers, but Congress promises to offer cashless insurance of up to ₹2.5 million to the poor, whereas CPI(M) pitches free and universal healthcare. BJP echoes its 2019 promise of expanding the Ayushman Bharat Scheme for free health services, and this time, specifies a focus on prevention and reduction of women’s cancers.

Parties have flirted previously with cash transfers as a way to boost the care economy. In the 2021 Assembly Elections, West Bengal, Kerala, Assam and Tamil Nadu Governments pitched monetary compensation for homemakers. Goa started the Griha Aadhar scheme last year to provide “support to the housewives/homemakers from the middle, lower-middle and poor sections of society, to maintain a reasonable standard of living for their families.”

Source: India Time Use Survey (2019)

About paid care giving

Even when caregivers are paid, a great deal of caregiving is done by workers in the informal sector. Shortage of care workers, poor working conditions and lack of protections plague the provision of care.

Congress’s Nyay Patra promises to double the salaries of frontline health workers including Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), Anganwadis and Mid-Day meal cooks. To reduce the workload, they mention doubling the number of Anganwadi workers and creating an additional 14 lakh jobs. The care workers’ core demand — of making them permanent, salaried government workers — has not been addressed.

The number of domestic workers in India fluctuates between four and 50 million depending on how you define the term. Reports reveal India’s domestic workers are underpaid and overworked, facing routine discrimination and abuse from employers in the absence of legal safeguards. In it manifesto, Congress proposes to regulate the employment of domestic help and migrant workers. The manifesto also mentions “sufficient night shelters for migrant women workers and adequate number of safe and hygienic public toilets for women.” DMK promises to enact a law to safeguard the rights and minimum wages of domestic workers.

Both these categories come under the unorganised sector, for which different parties have varying propositions. CPI(M) plans to introduce a law for universal social security coverage for unorganised workers, including maternity and childcare benefits. Congress vows to “protect the rights and enhance the social security provided to gig workers and workers in the unorganised sector).”

However, Tanya Rana, gender and governance scholar at CPR India, does not believe the “appeals of ‘voluntary’ care workers have been materially addressed” yet.

In the formal sector, social workers, registered nurses, medical doctors, occupational therapists and physiotherapists perform caregiving. Congress has promised to pass a law to penalise “acts of violence against doctors and other health professionals while performing their duties.” Other priorities include increasing budgetary allocation to these fields; doubling “hardship allowance of doctors serving in rural areas,” and ensuring hospitals and medical colleges function only if 75% of its posts are filled.

About upskilling

Focusing on skilling, reskilling and upskilling to create a trained care workforce can meet the growing demand for care work in India and “also contribute towards India becoming the global care workforce capital,” a recent policy document noted.

DMK has pledged interest-free loans of up to ₹10 lakh to women-run Self Help Groups (SHGs). In a similar vein, the BJP proposes “integrating women SHGs into the service sector” to aid market access.

Congress says it “will vastly enhance the institutional credit extended to women,” through boosting the capacity of SHGs, Non-Banking Financial Companies and Micro Finance Institutions. The party also plans to re-introduce the Bhartiya Mahila Bank under an all-Women Board of Directions “that was wound up by the patriarchal BJP/NDA government.”

Reservation guarantees and employment opportunities for women are also in the mix, albeit not with the explicit purpose of compensating for women’s car giving roles. Congress plans to reserve 50% of government jobs for women starting 2025. BJP assures the implementation of the Women’s Reservation Bill after the delimitation exercise slated for 2026; others including the DMK, CPI(M) and Congress vow to enact the legislation without delay.

Boosting paid care infrastructure

Universal and public child care, access to transport and safety, along with flexible working arrangements and leave policies allow caregivers the opportunity to enter paid work. Provisions like hostels and creches are aimed at addressing the demand-side barriers to women’s participation in paid employment activities, says Ms. Rana.

BJP’s manifesto focuses on infrastructure development: promising to erect hostels and creches for working women, with “the specific focus on locations near industrial and commercial centres to facilitate increased participation of women in the workforce.” The Congress too plans to double the number of working women hostels, with at least one Savitribai Phule Hostel in each district.

The DMK has promised a law to provide menstrual leaves to women if it comes to power. The Congress, on the other hand, mentions measures to ensure fair and equal wages, creating safe places for work, measures such as fair and equal wages; safe places of work; childcare services; preventing sexual harassment and violence; and extending maternity benefits.

BJP’s Nari Shakti agenda does not specifically mention policies that can open up new female labour force participation opportunities. Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2022 noted that flexible work hours and system aligned with this could herald new sectors for women. Ashwini Deshpande and Naila Kabeer’s scholarship shows that women express a demand for work that is compatible with household chores.

What would an ideal care economy policy look like?

Policy must “spend more on the care economy, pay care workers adequately, value social workers as much as we value engineers, offer women longer tenures in their careers to compensate for the time lost during maternity, or scale up income transfers to women for the invisible care they provide,” economist and author Shrayana Bhattacharya wrote in an article.

ILO calculations based on labour force and household survey data; UNESCO, 2018; ILO, 2017; OECD, 2017. Photo Credit: “Care Work and Care Jobs: For the Future of Decent Work” report by the ILO.

Political parties are chasing after the women’s vote with promises of welfare and freebies, as the number of women electors grows. Still, the “caregiving” aspect or care economy is not definitely articulated in election manifestos. ”Even current talk seems cursory. There is no real debate among our representatives on this issue today,” says Ms. Rana. In the current pick of election manifestoes, the care economy is vaguely referenced and indirectly addressed, with no explicit mention of the disproportionate, gendered burden on caregivers. While “maternity benefits” and “creches” find mention, there’s little accommodation for flexible work or paternity leaves that would allow the care giving burden to be distributed equally within a household. The real “culprit” caging women caregivers are the “cultural norm that places the burden of domestic chores almost exclusively on women,” noted Dr. Deshpande and Dr. Kabeer.

Some gaps are more conspicuous than others. Parties have made no clear mention of flexible work policies, maternity and paternity leaves, or formalising female healthcare givers in the workforce. The broad strokes of “women” and “Nari Shakti” do not offer clarity about which women these services apply to. Congress’s manifesto, for instance, promises to strongly enforce laws intended to prevent offences against women, such as the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 and the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. These laws do not apply to people working in the unorganised sector and the gig economy, since they carry strict definitions of “employees”, “workplaces” and “employers.” The ILO estimates that at least 81.8% of women’s employment in India is concentrated in the informal sector.

Other limitations are discreet and disguised. Mainstreaming caregiving in the electoral landscape has to contend with opposing forces. Policies such as water or fuel schemes, cash transfers, or making wages conditional upon housework in a patriarchal setting “further entrenches housework as women’s work” and does little to challenge the gendered expectations of work within the home, says Ms. Rana. On the other hand, given how ubiquitous and entrenched unpaid care work is, adding compensation offers economic visibility to women.

Routes of maintenance and maternity benefits are pitched as compensations to women, but the current political and legal perspective does not make the process of caregiving “easier or more rewarding,” Chadha Sridhar wrote in a 2022 paper. “There is nothing to give them recognition and rights, or ensure that the division of responsibilities and labour is more equitable.”

What shape and voice would an ideal policy for women caregivers take? A 2024 government policy document has five broad ideas: implementing leave policies, subsidising care services (for children and elders alike), investing in care infrastructure such as creches and elder care centres), upskilling and monitoring of the caregiving process to ensure quality and safety. The United Nations has a ‘Triple R Framework’: to recognise, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work, along with rewarding and representing care workers.

For electoral promises to align with ground realities, a more tangible and timely recommendation demands attention, says Ms. Rana. It is also imperative to release regular statistics of time use to quantify women’s time, and find ways to improve the calculations and measurements of the work women, the majority of care givers, undertake. This could reform the pitch, policy and promises geared towards the care economy.

“None of these policies are trying to change [and challenge gendered norms of caregiving] at the societal level.”Tanya Rana, gender and governance scholar