The momentous ending of Sheikh Hasina’s rule is both a moment of opportunity and risk. In order to understand it, we need to place Bangladesh’s experience in the broader context of democratic institutionalisation. But for India it is vital to not view Bangladesh within the frame of our own narcissism. This revolution belongs to the people of Bangladesh, and it is a moment in their often fraught quest to make their own destiny on their own terms.

India has vital interests in Bangladesh. Bangladesh should not become a staging ground for anti-India groups operating in the North-east. Any violence against Hindus in Bangladesh, even if it is an aberration, will have a profound impact on domestic politics in India, which in turn will affect Bangladesh politics. So far, the army and the student movement in Bangladesh are giving every positive indication of not letting this happen.

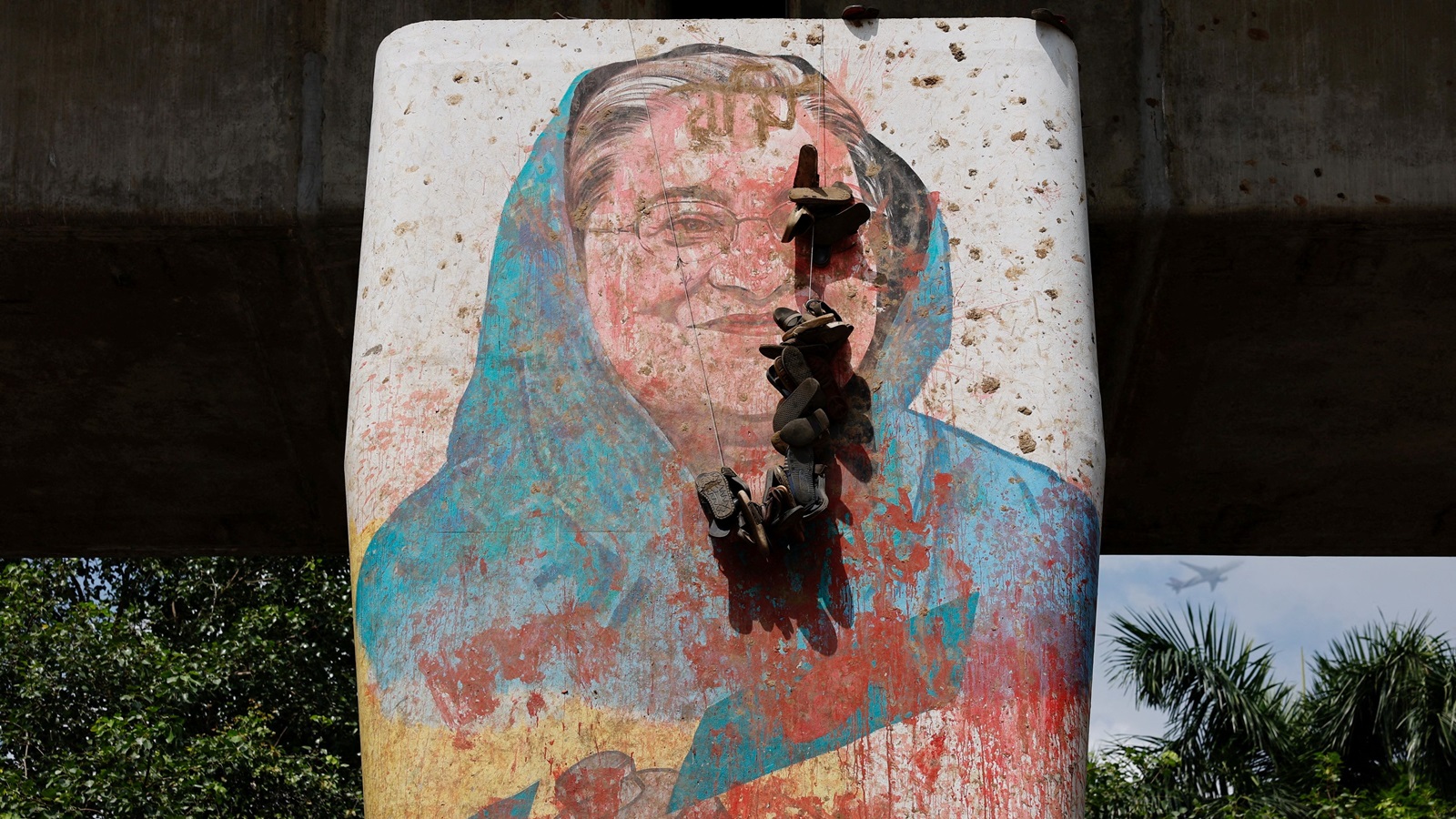

But our degree of narcissism has blindsided us. At the governmental level, it led us to ignore a central fact of modern politics. Authoritarian repression can work only up to a point; dissent, like water, will find its outlet eventually. So, we sided with Sheikh Hasina well beyond what legitimate concerns warranted, and risked becoming a partisan actor in Bangladesh politics, not just on the side of one party but of authoritarianism. At the level of civil society and the media, we have refused to acknowledge the complexities of Bangladesh as a society.

The Indian right wing’s construction of this event as simply a foreign conspiracy of sorts or simply in an Islamist frame, is the surest way of alienating the Bangladeshi people. It is a way of calling them dupes, with no agency of their own, roughly the same way in which the Right thinks of domestic dissent in India. It is the same mistake that Hasina made by calling her own students Razakars.

Bangladesh politics has been marked by two difficult tensions. To simplify somewhat, its creation as an independent nation did not fully resolve the question of its identity as a religious or a secular nation with a dominantly linguistic nation. Successive rulers, most notably Ziaur Rahman, attacked the integrity of a possible secular future for Bangladesh both by incorporating a more Islamic hue into the constitution and giving more space to Islamist groups to the point that they are a significant feature of Bangladesh politics.

Sheikh Hasina also accommodated them in part in response to mass mobilisations against atheist bloggers. But ironically, she also used the religious pretext to legitimise various laws clamping down on freedom of expression which could be turned as easily against her secular opponents. So Islamism will remain a strain in Bangladesh politics.

But the construction, in India, that only a pro-India authoritarianism can keep Islamism at bay has got things backwards. In part, Islamism thrives either because it has the patronage of autocrats who use it, or because the secular opposition has been so suppressed that religious mobilisations are the only available expression of discontent. It will likely be the case that as democratic spaces open up, Islamist groups will become more visible for a while. But as with all modernising societies, we have to look at the long game.

There is no guarantee of anything in a democracy, but Bangladesh has some chance, albeit with some conflict, of making it. The character of civil society in Bangladesh is different from Pakistan. It must be remembered that even in Pakistan religious parties don’t do well in electoral politics. Their power is often sustained by the fact that, apart from state patronage, they are, in so many areas, substitutes for the state. Bangladesh has a robustly institutionalised secular civil society organisation, one that has been central to its developmental story. It is possible for Bangladesh to think of itself as a possible zone of freedom, for a religious benchmarking of national identity will once again take it down the cycle of conflict and repression.

The second tension is the institutionalisation of the party system. The first order of business for an interim government will be to ensure free and fair elections, one in which all parties participate. A boycott by the Awami League, or lower turnouts will once again condemn the party system to slide from democratic upsurge to centralised authoritarianism. The problem has not just been that in Bangladesh winning parties have enjoyed monopoly of power, often targeting their opponents, making the commitment to free elections less fraught. It has also been that each of the parties, as we saw with Awami League recently, itself becomes a small cabal, controlled by an opaque inner circle, increasingly unresponsive.

Perhaps with the shadow of Sheikh Hasina and possibly even Khaleda Zia fading, a genuine party system might emerge. But creating a party system more attuned to rotating and sharing power, and more committed to a core set of institutional values, will be crucial. Otherwise, the current tendencies — social movement upsurge, followed by brief democracy, then consolidation of an autocratic party affiliated state — will continue.

It is for this reason that student movements have been so powerful in Bangladesh. They were at the forefront not just of the language movement in 1952 or the independence movement in 1971. Bangladesh is unique in the degree to which students retain the aura of democratic legitimacy in constantly challenging authoritarianism. In a system that by turn becomes authoritarian, students are the ones who unsettle any established claims to authority. The image of the student Abu Sayed standing with open arms and within seconds being shot revealed the character of the Bangladeshi state in this moment like no other image could.

India had student movements during the Emergency. There were regional student movements, like in Assam. The last big student-led movement was the agitation for Telangana, but that did not turn violent because the state was responsive. Again, there is no guarantee. But the fact that Bangladesh is a student-led movement holds out the possibility of hope — a sign of a society contentiously trying to carve out its own future.

The recent experience of how popular uprisings turn out across the world is not always encouraging. Apart from other things, Bangladesh will face economic headwinds. But no power, especially India, should short circuit the complex process of internal modernisation Bangladesh is going through, for its own short-term ends. And if Bangladesh can internalise the message of its students — that religious nationalism is the surest road to authoritarianism — the region will have a fighting chance.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express