On August 6, the streets of Dhaka echoed with the cries of the desperate and the defiant, as an uprising ignited the city with unparalleled fury, one that had been simmering for far too long. Six months into an electoral triumph, alleged to be a rigged project, it had been ignored by an arrogant, authoritarian dispensation. Over 100 people were killed in a single day, the acrid scent of smoke mingling with the metallic tang of blood, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina had to finally resign and flee the country as violence and anarchy grew unchecked and unrelenting. The world’s most celebrated garment exporter had suddenly become a quasi-banana republic. Most analysts from Bangladesh believe that the protests that turned egregiously bloody weren’t solely about the 30 per cent quota reserved for the families of freedom fighters of the 1971 War of Independence; rather, they reflected the youth’s broader frustrations with limited economic opportunities, stifling autocracy, and a miasma of hopelessness.

A national security issue

In the early 1990s, economist Nick Perna first coined the term, “jobless growth”: It refers to a situation where the GDP could be increasing but employment is either stagnant or decreasing. Many nations, with their eyes firmly fixed on the rising graphs of GDP, a low-hanging fruit for political campaigning, make the critical error of treating “jobless growth” as merely an economic anomaly, without realising its deleterious social consequences. They perceive it as a temporary divergence and a solvable riddle within the limits of economic theory and time (the hard truth is that most politicians don’t understand the E of economics). But history is a cruel leveller; it can shatter the rose-tinted glasses that create these spectacular illusions.

The fact is that jobless growth is one of the major national security issues in low-middle-income countries. The Arab Spring of 2010 and the January 25 Revolution in Egypt, the persistent protests seen in numerous African and Asian countries, serve to illustrate the destabilising effects of jobless growth on national security. The ILO had warned that the youth unemployment crisis, especially after the pandemic, was a ticking “time bomb”, but most countries were blissfully nonchalant, happy with their K-shaped recoveries. The Gen Z protests in Kenya forced the government to take corrective measures following police brutality. If we were to add the cost of mental health on jobless youth, it would be astronomical. Bangladesh stands as the most recent illustration of this trend.

The cost of willful ignorance

Richard Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, once disdainfully referred to Bangladesh as a “bottomless basket.” Today, however, Bangladesh’s banking sector is a model for many countries, and its export-led growth model has yielded considerable returns for the nation. Its per capita income is now higher than that of India. The biggest issue plaguing Bangladesh is jobless growth: The country’s GDP was growing at 6-7 per cent in the last decade, yet, its employment was growing at only 0.9 per cent. Since 2002, the elasticity of employment growth to economic progress has markedly diminished across various demographic categories — urban, male, and female. And much like most myopic low-middle-income nations, the policymakers of Bangladesh failed to grasp the political perils inherent in such a growth paradox. Extensive research across numerous countries has shown a strong positive correlation between unemployment and political violence; the rise of social media has given the youth greater networking platforms which can overnight morph into a gigantic movement.

Sheikh Hasina, blindsided by kowtowing sycophants, missed the woods for the trees. The trigger was the abject dreamlessness of Bangladesh’s young. A maelstrom of disorder followed.

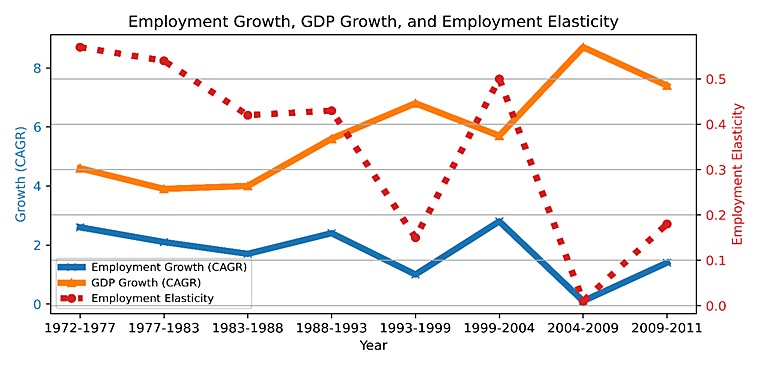

The disquieting phenomenon of jobless growth is on the cusp of eliciting intensified scrutiny, particularly in the aftermath of the recent vicissitudes of Bangladesh’s volatile society. Politicians cutting across partisan trenches in India will be profusely naïve to ignore the lessons from other countries like Bangladesh. From 1972 to 1983, every 1 per cent uptick in GDP growth resulted in a 0.5 per cent increase in employment (See Figure). In the last decade, however, GDP has grown at 5.9 per cent but employment growth has slowed down to 1 per cent or even less (the government data has been furiously disputed by economic experts). Thus, each 1 per cent expansion in the GDP now engenders a trifling 0.1 per cent rise in employment; it is ridiculously disproportionate. Economic growth, when it fails to create jobs and uplift the broader population struggling at the bottom and middle of the growth pyramid is not just meaningless — it is palpably fraught with a fallible social/economic model. The frustration born from unmet expectations of the youth, treated with sustained condescension and callousness, is a formidable trigger that can assume alarming avatars. Why India’s leaders remain oblivious to this is baffling.

Denial is not the answer

Disconcertingly, like Bangladesh, every government economist continues to dismiss jobless growth, let alone acknowledge its destabilising effects on the nation and the economy. Recently, one economic advisor branded jobless growth as a “red herring” — a term that, in this context, seems more apt for describing the smoke-and-mirrors projections coming from the powers that be. Not to be outdone, another advisor hailed the Modi government’s job creation as a historical record; a hallucination so monumental it seems to have slipped under the radar of common sense and statistical rigour.

Indeed, the Modi government should worry about the many cases of cancelled examinations (NEET, etc), scams in UPSC hiring, the 9.2 per cent unemployment in June 2024 (as per CMIE), the 50 lakh people applying for 60,000 jobs to become constables in the Uttar Pradesh government, etc. It is a long list.

Politicians must stop the braggadocio about becoming the third-largest and a $5-trillion economy (which would happen inevitably as per normal growth under even a mediocre government) and instead focus on health and education, per capita income, reducing income inequalities, improving India’s Human Development Index value, social security benefits, addressing informal sector woes, minimum wages, etc, and create an egalitarian society based on inclusive growth. Budget 2024 was a manifestation of the fact that the government has belatedly acknowledged the ballooning catastrophe on jobs, but it was like applying a band-aid to a broken bone. The process of mainstreaming India’s youth must start with robust earnestness. The time starts now.

Jha is a former Congress leader and a political analyst. Mukhopadhyay analyses data on economic and political trends