Amid polls to constitute the 18th Lok Sabha, the governing party and the opposition have clashed over a critical question — how much inequality is India willing to tolerate? In its manifesto, Congress has promised to conduct a nationwide caste census to determine the socio-economic conditions of various caste and sub-caste groups. Congress functionaries have taken umbrage to the unfair concentration of wealth in the hands of a select few individuals.

BJP has hit back, accusing Congress of appeasement politics and termed this exercise an attempt to extract private wealth from individuals and redistribute it among minorities.

The issue is philosophical: to whom do a country’s material resources belong? As this debate rages on in election rallies and across TV newsrooms, the

Supreme Court

is quietly preparing to answer this question. While deciding a seemingly innocuous set of property disputes originally filed in 1992, the SC has felt the need to re-interpret Article 39(b) of the Constitution, a directive principle of state policy which urges the state to make policies to ensure “that the ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as to best subserve the common good”.

Not just an academic question

Generally, directive principles of state policy are unenforceable by a court of law. A member of the Constituent Assembly even described the entire part as a ‘dustbin of sentiment’. But Article 39(b) is different. It is underwritten by Article 31C — which provides that a law made by Parliament in furtherance of Article 39(b) is not invalid even if it violates fundamental rights such as equality and freedom of trade. It is worth mentioning that the linkage between the two provisions is also an issue before the Supreme Court in this very case.

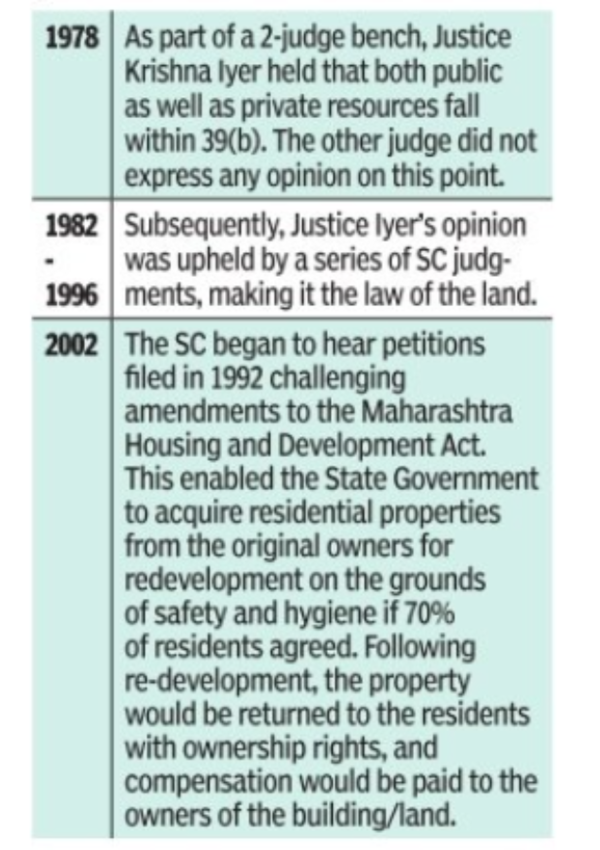

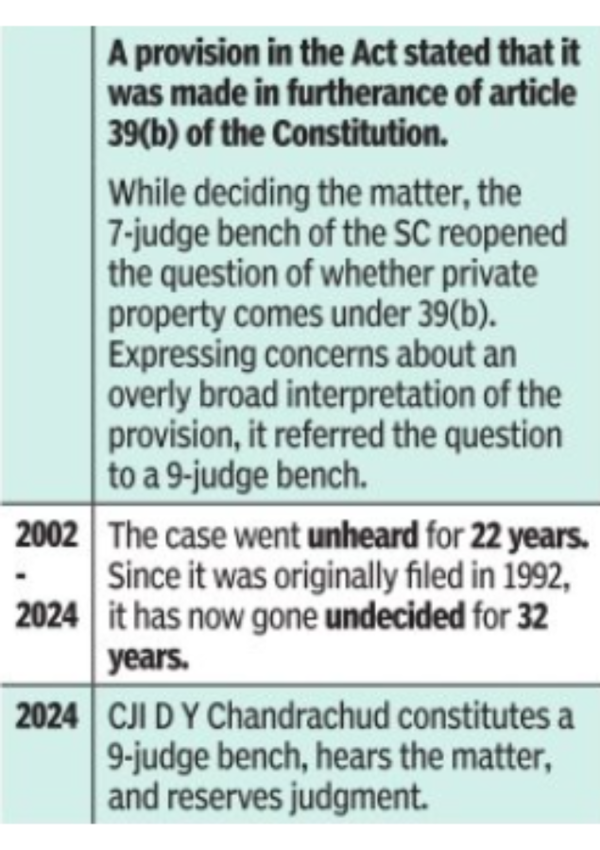

The trajectory of the case

Of course, the expression ‘material resources’ must include public resources. The question is simple: does it include private resources as well?

What are the possibilities?

A recent study by the World Inequality Database has stated that

wealth inequality

in India is now higher than what it was during British rule in India. In light of this, Parliament could potentially enact a ‘wealth tax’ where all citizens with a certain net worth would be taxed 2% of their wealth. Challenging the law because it violates fundamental rights such as equality, life and personal liberty, and freedom of trade would be futile, because Article 39(b), backed up by Article 31C, would kick in.

Another example includes a law to acquire all privately held forest land across the country and distribute it among tribal communities who are displaced by climate change, infrastructure projects, internal conflict etc. A mere reference in such an Act to Article 39(b) will save it from being struck down.

The real implications

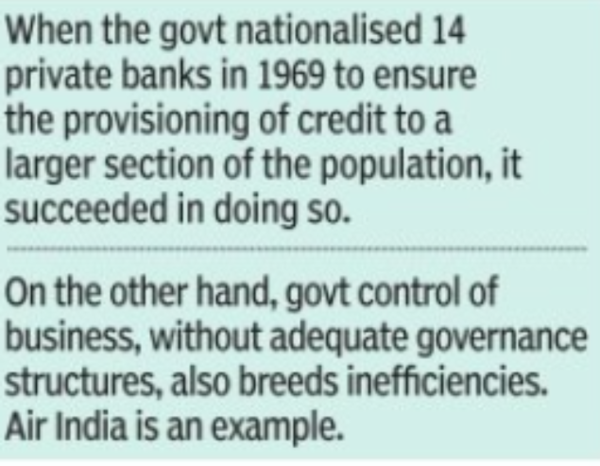

The implications of this case go beyond the immediate political debate. Its significance lies in how the apex court interprets the constitutional guarantee of equality, and how much power it gives to the state to fulfil this guarantee. A restrictive interpre tation will assign the role of reducing inequality to the private market, hoping that ‘invisible hand’ will reach everyone. A broader interpretation will give greater powers to the state to interfere in private affairs to ensure proper redistribution of wealth.

Underlying this provision is an assumption that the state may be better capable of ensuring equality. This may be true in some cases, but very false in others.

A Gandhian vision of Article 39(b)

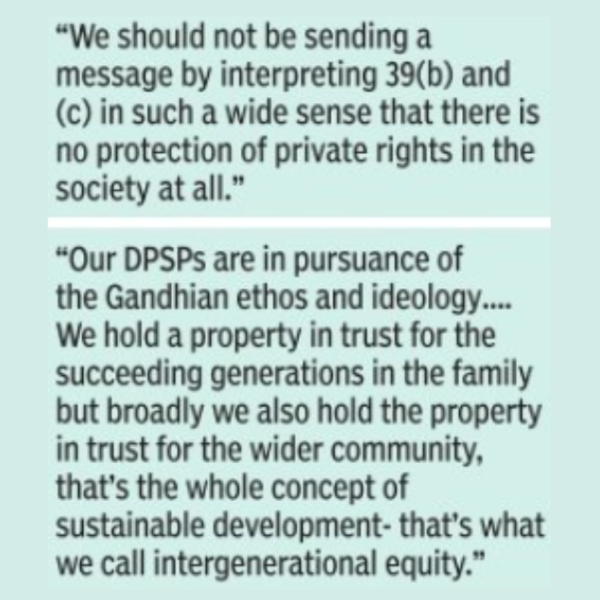

During the hearings, CJI Chandrachud stated that Article 39(b) could not be interpreted in a purely communist or socialist sense. He seemed to detect a Gandhian flavour to the provision.

It is hence likely that the SC will give us a more nuanced interpretation of Article 39(b). Private property may not be wholly excluded, but certain kinds of private property may be declared to be held in trust.

The authors are with the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy