Opinion by Sanjay Srivastava

Instead, they could be the consequences of the real aspects of American identity

Mar 22, 2025 09:22 IST First published on: Mar 22, 2025 at 07:20 IST

The German political philosopher Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) — the author of the influential book, The Origins of Totalitarianism — considered that of all the major world powers, only the United States had never been an imperialist one. This perspective, as has sometimes been pointed out, was linked to Arendt’s vision of the US as a key site of anti-totalitarianism. It also blinded Arendt, as has also been suggested, to the politics of race and racism in that country. As a German Jew, she fled Germany to escape the very real dangers to her life posed by anti-Semitism, arriving in the US in early 1941. For Arendt, it was unthinkable that the political and social life of the country that had given her shelter from Nazi Germany could, in any way, be linked to global histories of colonialism and empire. The American context of race relations, she was to suggest, had little to do with the histories of Europe’s interactions with Africa. Arendt delinked African-American resistance movements — and America — from global trends.

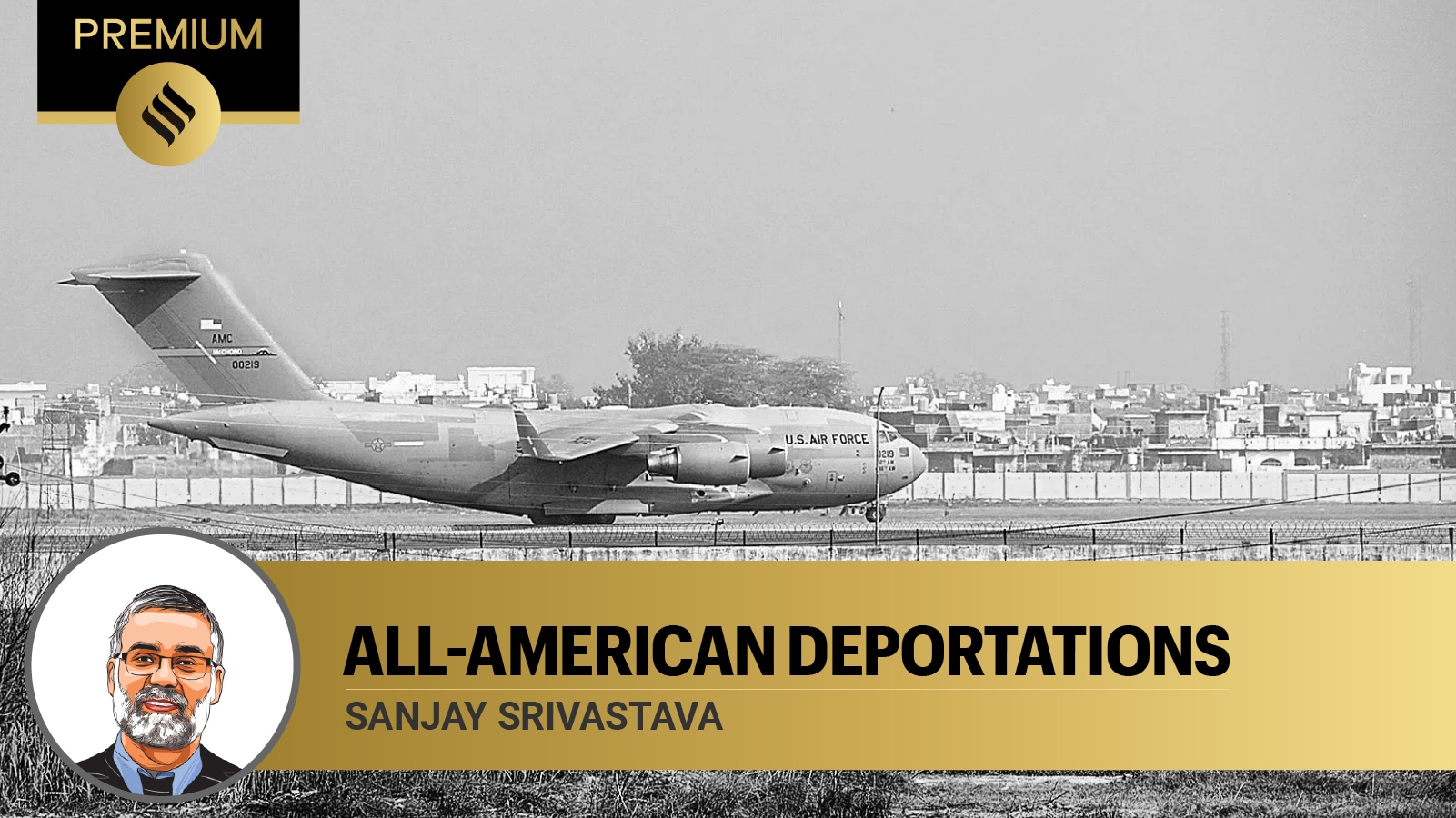

The Arendt conundrum — thinking globally about totalitarianism but locally about what happens in America — lies at the heart of recent episodes of deportations of those accused of “anti-Semitic” and “pro-terrorist” sympathies under the second Trump presidency. Of the several cases that are in the news, three have gained particular media prominence. Doctoral student Ranjani Srinivasan has had to leave the country, doctor and professor Rasha Alawieh has been deported and Green Card holder Mahmoud Khalil is in detention. Each of them has been accused of sympathising with — what the current American dispensation considers — “terrorist” activities. The equation of any criticism of the state of Israel with anti-Semitism is, of course, an important background to these current events. These, in turn, have become interwoven with ideas of “national security” and “public safety”. “National security” and political ideologies are, as we know in India, entangled contexts.

Story continues below this ad

The first aspect of the Arendt conundrum concerns American identity. If you consider its global footprint, American identity is arguably the most successful of all national identities. No other culture has achieved such transnational impact. If there is something called “global culture”, it is American. Financially, militarily or culturally, no other society has such an extraordinary global footprint. One way or another, in different ways, the contemporary human condition is American. And yet, just as strangely, notwithstanding the universality of American culture — and the self-confident identity it is linked to — it derives its meaning from unshakeable provincialism. For many Americans — President Donald Trump may believe the majority — the deportations may not seem problematic since American culture has historically been imagined as entirely self-contained and self-defined.

Expulsions from America are not a Republican phenomenon. They are an American phenomenon. The 18th–century Alien Enemies Act that finds such great favour with the current American president was formulated for use under conditions of war. However, given the historical development of Americanism as a self-contained fortress-culture, it is not surprising that there is no mass opposition to its deployment. Fortresses are invariably imagined as under threat of invasion and siege.

The second Arendt conundrum is the deep self-professed nature of American individualism and its apparent conflictual relationship with centralised forms of power, particularly the state. This relationship finds considerable play in both popular folklore as well as formal legal procedures. The mythology of the “outlaw” has been a key aspect of ideas about American identity. Embodying characteristics of self-reliance, straight-talking and deep suspicion of hierarchies, the outlaw stood (and stands) for a very powerful strand within the cultural imagination of the American self. This was the idea that there must be constant vigil against governments and state power that threatened two “fundamental” aspects of being American: Individual action and liberty. The outlaw was seen to both define and defend the most sacred of “American values”, that of individualism.

Story continues below this ad

Suspicions against state power have also played out from within the state itself. There is, for example, a variety of constitutional provisions that limit the reach of the state in the life of citizens. The Bill of Rights, which includes provisions against state interference in religious activity (the First Amendment) and the right to bear arms (the Second Amendment), are formal expressions of the cultural ideals represented by the outlaw.

most read

And yet, notwithstanding the pervasiveness of the “individual versus the state” dialogue and the implicit elevation of the individual as a heroic figure within American culture, the current deportation episodes are remarkable for how easily Americans allow their state to speak on their behalf. In the case of Alawieh — as well as members of a Venezuelan and Salvadorian gang who were also deported — the American state ignored orders by American judges to delay or halt its actions. There have been, however, no large-scale protests against the arbitrariness of state action in a society whose founding myth so strongly derives from notions of the sanctity of individual liberties and the need to keep state power in check.

The deportations, in this light, may not be as much of an aberration as unsurprising consequences of real, as opposed to imagined, aspects of American identity and culture. The problem, as with Hannah Arendt’s view of the American way and life, may lie in treating a culture and society as exceptional and unique. Cultural exceptionalism — the “shock” at what is happening in America at this moment is a good example of this attitude — is at the heart of the problem of how much we allow certain societies to get away with.

The writer is distinguished research professor, SOAS University of London

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd