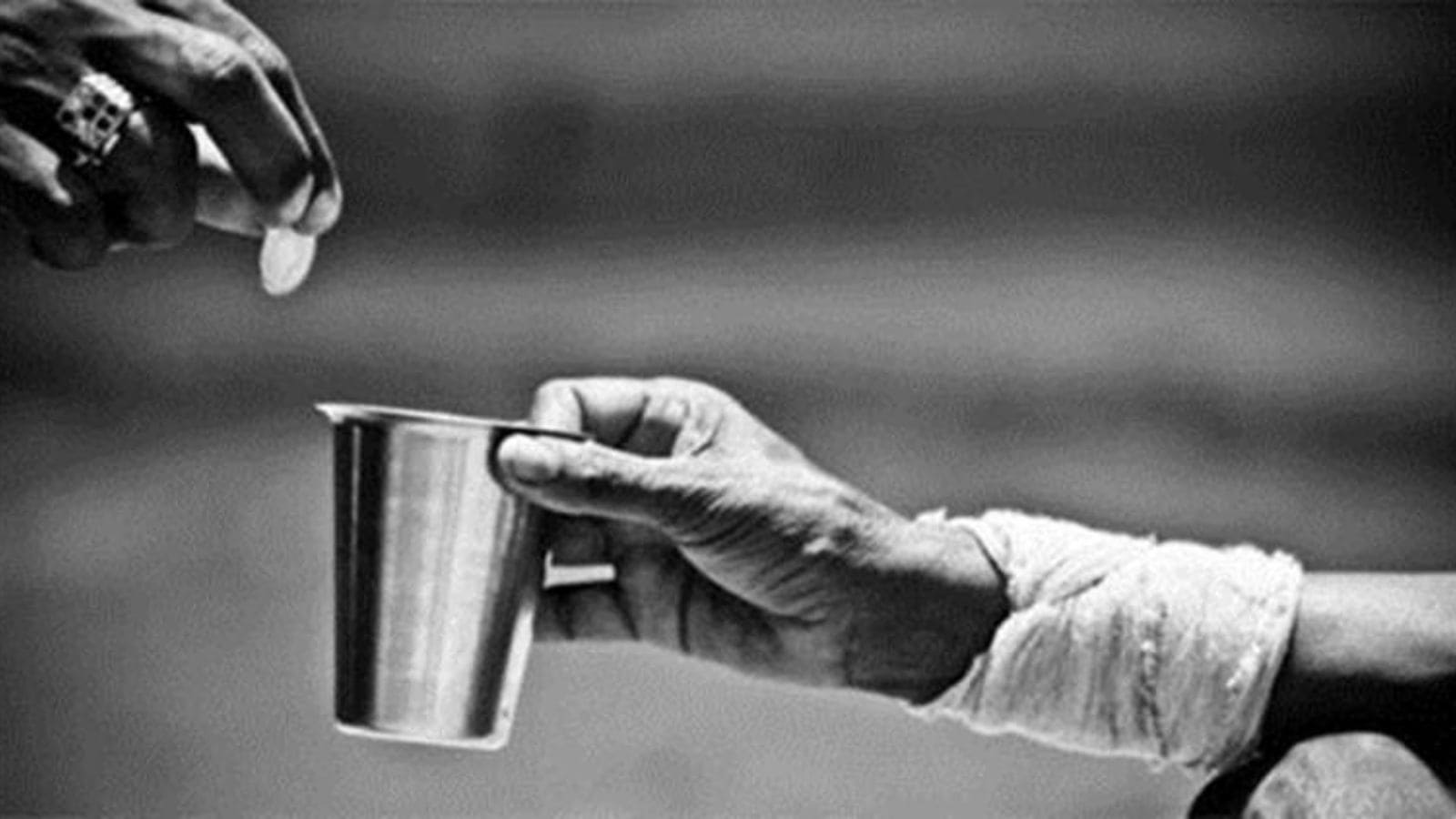

On December 16, Indore’s district collector issued prohibitory orders under Section 163 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), banning the giving of alms to “beggars”. This initiative is part of the Union government’s Support for Marginalised Individuals for Livelihood and Enterprise (SMILE) scheme, launched in December 2022, with the aim of rehabilitating “beggars” by providing them with medical care, education, and skills training — thus making Indian cities “beggar-free” by 2026.

The concept of a “beggar-free” city brings to mind the events surrounding Delhi’s preparations for the 2010 Commonwealth Games. As Delhi was spruced up with landscaped public spaces and swanky infrastructure, the then-social welfare minister called for eliminating the “nuisance” of “beggary” to make the capital a “world-class city”. Consequently, the Delhi government declared “zero-tolerance zones” for “beggars”, as mobile courts and enforcement vans went around arresting the poor and homeless, alongside slum dwellers and street vendors — those seen as incompatible with the image of a “world-class city”.

The events that unfolded in Delhi offer important lessons for the SMILE scheme, highlighting how efforts to make a city “beggar-free” have had troubling consequences for its poor. To better understand the state’s punitive approach to “beggars”, a look at its entrenched history with colonialism is necessary. We must begin with a fundamental question: Who exactly is a “beggar”?

Defining a ‘beggar’, legally speaking

The Constitution of India, under the Concurrent List, empowers both the Union and state governments to enact laws concerning “vagrancy, nomadic and migratory tribes” (List III, entry 15). During a Constituent Assembly discussion on the draft of the Indian Constitution on September 1, 1949, member Raj Bahadur argued for further adding “control and eradication of beggary” to the Union List. He argued: “Some people turn to beggars only because they are too lazy to work. They fill their stomachs without earning their livelihood by honest work. They simply live on alms and do not work. They are a burden on society.” In response, B R Ambedkar argued that “beggary” was already addressed in the Concurrent List under “vagrancy” for both the Centre and states to address and thus did not need to be added separately.

This discussion raises two significant points. First, the historical association of nomadic tribes with vagrancy was rooted in colonial policy. As Meena Radhakrishna details in her book Dishonoured by History: ‘Criminal Tribes’ and British Colonial Policy, nomadic tribes were criminalised by the colonial state through the 1871 Criminal Tribes Act. Driven by both prejudice and economic motives — such as maximising land revenue and safeguarding private enterprise — the colonial administration sought to “reform” itinerant communities through forced sedentarisation and wage labour.

Second, Bahadur’s framing of beggars as lazy and undeserving echoes similar attitudes from late medieval England. In his paper, ‘A Sociological Analysis of the Law of Vagrancy’, William Chambliss showed why the Ordinance of Labourers of 1349, England’s first proper vagrancy statute, was enacted after the Black Plague. Since the English economy was heavily dependent on a ready supply of cheap serf labour, the dearth of the labour force due to the pandemic meant a decrease in the surplus produced by the serfs and accumulated by feudal lords, along with the serfs searching for higher wages and better working conditions in the emerging towns. To counter this shift and safeguard the feudal lords’ surplus, it became crucial to frame the non-working poor as lazy and sinful and restrict their movement in public spaces. Marie-Eve Sylvestre, in her essay ‘Crime and Social Classes: Regulating and Representing Public Order’, shows how this was the beginning of a series of statutes in Anglo-Saxon countries that framed the poor as “morally inferior, lazy, and dishonest individuals who are to be blamed for their own misfortunes and treated as criminals or potentially serious offenders.”

most read

The retention of this colonial logic in Indian law has allowed states and union territories to enact anti-beggary statutes. The Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959 — the Act that serves as the definitional basis of the SMILE scheme — identifies “begging” not only as the act of soliciting alms but also activities like performing on the streets; selling items to earn a livelihood; or merely appearing destitute with no visible means of subsistence. One can see how the definition retains the colonial prejudice not only against the country’s poor but also against thousands of nomadic communities. This categorisation gives the police and district authorities a free hand to round up these groups to “beautify” public spaces, as we saw in the case of Delhi.

A shift in jurisprudence?

Recent years have seen some positive developments. In 2018, the Delhi High Court struck down several provisions of the Bombay Act as “manifestly arbitrary” and in violation of Article 21, which guarantees the right to live with dignity. The court questioned how the state could criminalise begging when it failed to provide basic necessities. Further, in July 2021, the Supreme Court refused a PIL seeking to remove beggars from public spaces, stating it would not adopt an “elitist view” to ban begging, which is a socio-economic problem.

The SMILE scheme not only presents an opportunity to address urban poverty constructively but also to rethink the legal and juridical construction of “beggars” and “vagrants”. Otherwise, its reliance on outdated definitions and punitive frameworks raises concerns about its efficacy and fairness.

The writer is a Post-Doctoral research associate, Oxford university

Discover the Benefits of Our Subscription!

Stay informed with access to our award-winning journalism.

Avoid misinformation with trusted, accurate reporting.

Make smarter decisions with insights that matter.

Choose your subscription package