Days before the Champions Trophy, a Pakistan cricketer texted a curt reply when asked if their fans would miss watching Indian superstars Virat Kohli and Rohit Sharma. “Why don’t you ask these questions to Indian players?” Clearly, India’s refusal to cross the border hasn’t gone down well in Pakistan.

In 2023, after much hand-wringing, Babar Azam’s team travelled to India for the 50-over World Cup. Having taken the first step, the Pakistan Cricket Board had expected reciprocity. This ICC event means the world to them. India and its fans would have lit up the Champions Trophy, certified normalcy in the troubled country and given a fillip to its tottering economy.

Story continues below this ad

Reacting to the snub, Pakistan has now decided to avoid all India trips in the future. This isn’t rhetoric but a signed and stated official stand endorsed by the ICC. The cricket door between the two cricket-mad nations isn’t just shut, it’s been sealed and bricked.

It wasn’t always this bad. The last time Pakistan got to conduct a tournament of this magnitude was in 1996, when it co-hosted the 50-over World Cup with India and Sri Lanka. Eden Gardens had the opening ceremony, Gaddafi Stadium the final. It was an event that gave Pakistan an unprecedented windfall and also showcased the strength and solidarity of cricket’s now defunct Asian block.

Even before the first ball was bowled, a crisis would emerge. In a sudden turn of events, Australia, citing safety concerns over LTTE’s bombing threats, refused to travel to Sri Lanka. Overnight, a joint Indo-Pak cricket team was formed and put on a plane to Colombo to play an exhibition game against Sri Lanka. This was to make a point, show the West that Sri Lanka wasn’t what they perceived.

Story continues below this ad

That friendly game would start with Pakistan captain Wasim Akram getting Lankan Romesh Kaluwitharana caught by Sachin Tendulkar at short cover. For years to come, the most cynical subcontinent cricket reporters, after downing a few drinks, would get misty-eyed describing the sight of Akram and Pakistan players running towards Tendulkar and wrapping the Little Master in a big collective hug.

At that one-of-a-kind game, Indian captain Mohammad Azharuddin would say: “This proves to the world that we are together.” Akram would underline the subcontinental brotherhood. He wanted more such “joint team” games. Pakistan manager and former captain Intikhab Alam, a good old peacenik like his Indian friend Bishan Singh Bedi, called the occasion “historic” and “the turning point in the relationship of the two countries”.

Since that 1996 game, there have not been many such turning points. Wars, border skirmishes, terror attacks, and surgical strikes would build an overbearing atmosphere of mistrust between the two countries. Periodically, there would also be summit talks, breakthroughs, student exchanges and other peace initiatives. Depending on the political climate, India and Pakistan have toggled playing sworn enemies or long-lost brothers separated at Partition. As for Indo-Pak cricket, it remains the weathercock, relationship metre and, sadly, a perpetual victim of circumstances.

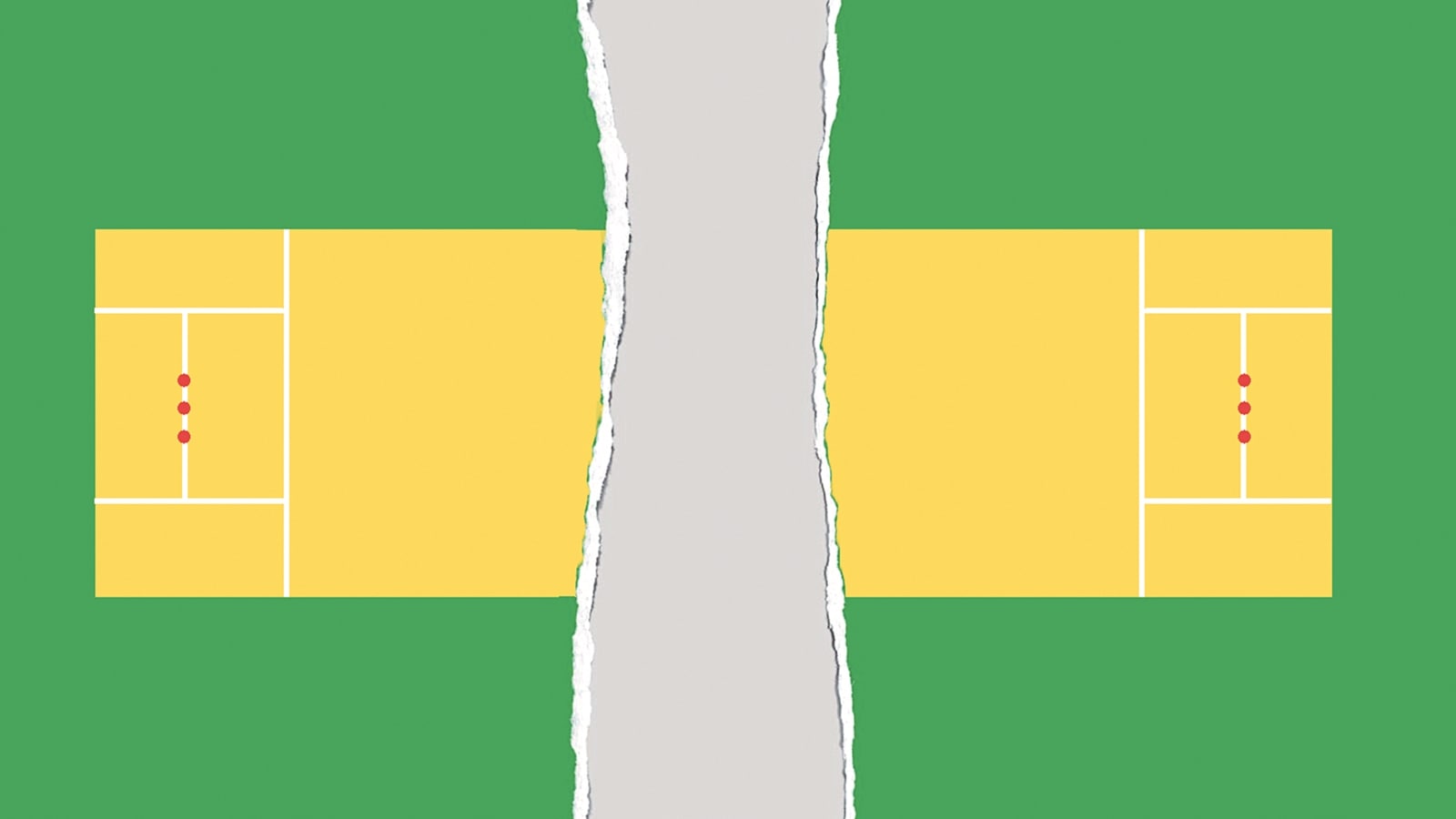

But this time, the neighbours seem to have drifted way too far. Reconciliation seems far-fetched. India’s insistence on not stepping on Pakistani soil resulted in rescheduling. One semi-final was moved to Dubai. And, in case India reaches the final, the host will also lose the right to keep the title clash in their country. So much for being the ICC-approved sole host. The hurt and anxiety can be felt in the voices from Pakistan.

The TV studios are brimming with anger. The fiery Pakistan cricketer wants a piece of paper when he is asked to predict the last four line-up. In both Urdu and English, he writes that India won’t reach the semi-final. He doesn’t give a cricketing reason, it’s what his dil tells him. That’s a heartfelt wish he shares with most of Pakistan. Which host nation would want the final, the climax of a grand event, to be wheeled out to foreign shores?

With stakes so high, the collective anxiety of the nation is rising. A recent loss to New Zealand in a pre-Champions Trophy warm-up tournament final brought them face-to-face with their fears. The nervousness would manifest as anger.

Sikandar Bakht, a lively pacer who bowled alongside fast-bowling legends Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz, can’t wrap his head around his country picking a medium-pacer in the Champions Trophy side. “These selectors are nalayak (good for nothing). Khuda ka khauf karo (Fear God), you have picked a 125 kph bowler in the team,” says the former player of a nation with a sparkling pace legacy. Rashid Latif, a seasoned World Cupper, sits for a rapid-fire round in another TV show. Name one player who doesn’t deserve to be in this team? “One? … There are six to seven,” he shoots back.

It’s not that 1996 didn’t have chaos and the usual subcontinent disquiet. Four years after they had blown away England in the 1992 World Cup final, Pakistan wasn’t quite the favourite but not as inadequate as now.

In the post-Imran era, the team had lost the aura. There was infighting, Akram and Waqar didn’t get along. The two were also among the four players caught smoking up on a beach in the West Indies. There were also match-fixing whispers. Team selection, too, was questioned. The inclusion of 38-year-old Javed Miandad, too, had a cloud of intrigue. It was because of pressure from Karachi. Had he not been named, MQM, the party of muhajirs, would not have allowed the event to unfold peacefully, it was reported.

Benazir Bhutto was the prime minister and the Muslim League was in the opposition. Corruption and income disparity had made the population cynical and politicians unpopular. But Pakistan, at that point in history unlike now, had the support of its neighbours, a better team and that one precious possession — hope.

They knew the two Ws could still be trusted to win games. Imran Khan, while raising funds for his cancer hospital, was slowly transforming from a social activist to a political alternative. The dream did come true but didn’t last long. Some years back, that hope virtually died. Today, Imran languishes in jail.

most read

Back in 1996, the World Cup had a theme song sung by the rock stars of the globally popular band Junoon. They kept repeating that one phrase: Pehchaan kabhi na bhulo. They were reminding the team and nation not to forget its identity and legacy. It was about coaxing the team to do a 1992 again, roar like Imran’s caged tigers. They couldn’t, losing to India in the quarter-finals.

This time around, the PCB has picked another famous singer to promote the event. Atif Aslam, like Junoon, has shot a video on the streets. But this time, the players aren’t in salwar-kameez, as in the Junoon video. They are in three-quarter shorts and keep mouthing — Kuch bhi ho sakta khel mein (Anything can happen in a game). In cricket’s unpredictability lies Pakistan’s hope this time.

Uncertainty is all very well on the cricket field. But there was a beauty of certainty to Indo-Pak cricket. The end of them hosting each other is cricket’s greatest tragedy.

sandeep.dwivedi@expressindia.com