At first glance, July 21, 1993, is unlikely to attract scrutiny in a documentation of the Left Front’s waning fortunes in West Bengal. In a state of protests and hartals, it could well appear to be just another piece of statistics. Yet, it is a date that marked a change in Kolkata’s dynamics with the Communist government. Led by Mamata Banerjee, then the state Youth Congress head, party workers and protestors had marched to Writers’ Building, the seat of the CPM government, demanding that voter identity cards be made the sole requisite for voting. Police intervention to manage the agitating crowd had gone awry that day — Banerjee had been intercepted at a distance from Writers’ but 13 party workers died in police firing. Later, the Congress and Trinamool Congress (TMC), the party formed by Banerjee in 1998, would commemorate July 21 as Shaheed Diwas (Martyrs’ Day); a committee would find that the police used disproportionate force to disperse the crowd. But much before that, and certainly much before Singur and Nandigram, July 21, 1993 burnished Banerjee’s credentials as the state’s dissenter-in-chief, the Pied Piper to Bengal’s masses.

A few months earlier, in January, she had had another run-in with the establishment during a protest outside then chief minister Jyoti Basu’s office, against a cadre’s sexual assault on a differently abled woman in Nadia. Banerjee had been arrested and put in detention. In 1990, during an ugly confrontation between Left cadres and Congress workers in south Kolkata’s Hazra, she had been hit on the head with an iron rod — an image of Banerjee, her head and arm bandaged, lying on a stretcher had roused public indignation against the strong-arm tactics of Left cadres. She had always been vocal, but by the time 1993 rolled in, with the experience of being one of the youngest MPs in Lok Sabha and frequent run-ins with the government, Banerjee had managed to breach the distance between trouble maker — the ruling party’s description of her — and mass leader. She had, so to speak, emerged as Didi who refused to be daunted or diminished by the Left’s dadagiri. Breaking away from the Congress in 1997, where her voice was getting undermined, and shaping TMC into a party of consequence in the state and the Centre bolstered that reputation.

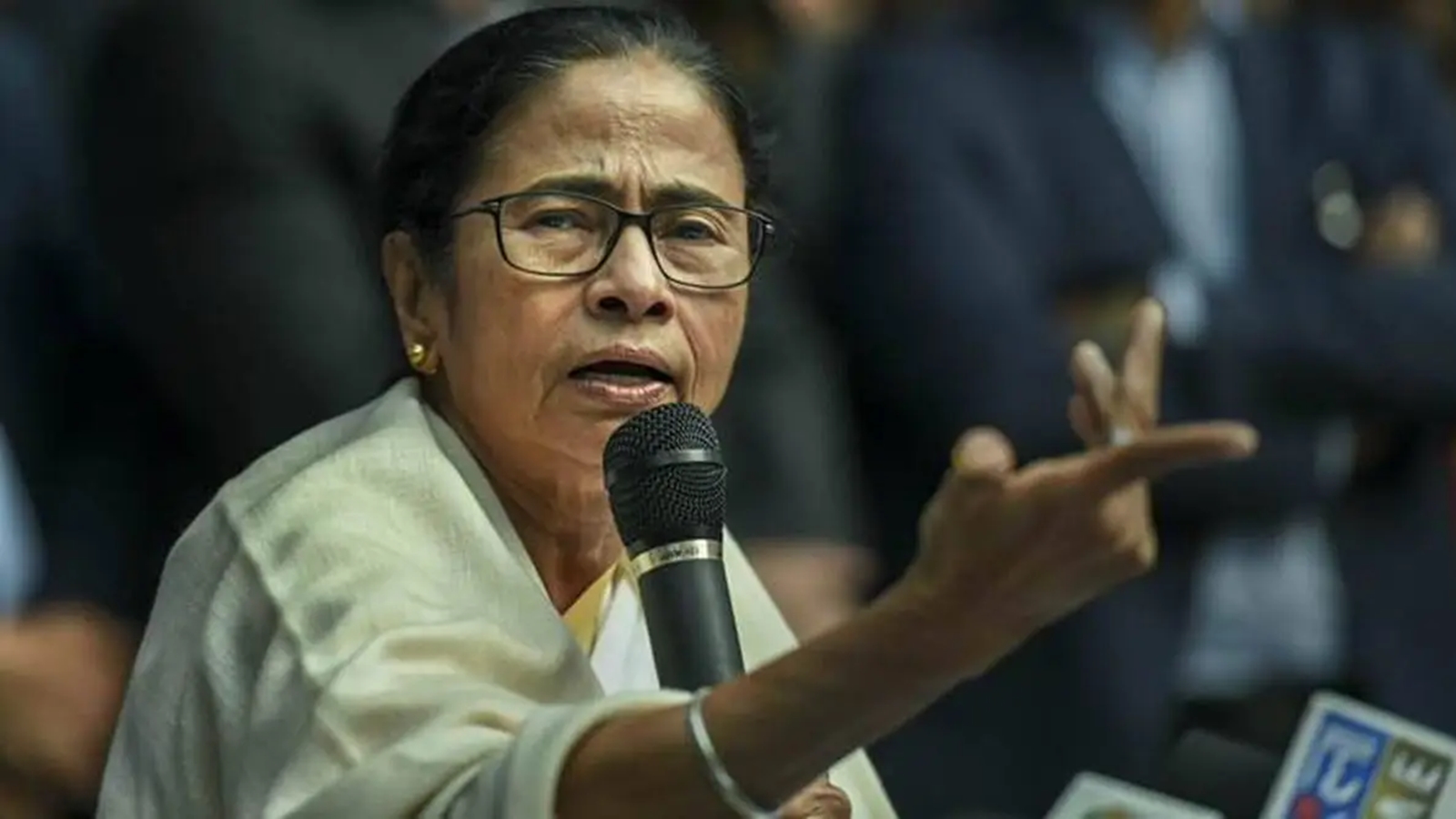

Three decades later, and a few months into her emphatic Lok Sabha election victory, Banerjee finds herself on the other side of the protests, fumbling to keep pace with the changing idiom of negotiations. Spontaneous people’s rallies against the rape and murder of a junior doctor at the state-run R G Kar Medical College and Hospital and demands for accountability have brought Kolkata to a standstill. Women — highlighted often as central to Banerjee’s administration and vote bank — have reacted to the incident with shock and anger. The striking doctors have refused the government’s offers for discussion unless they are live-streamed. Banerjee is the establishment now and the image of her waiting in an empty room for the junior doctors to come to the discussion table marks a turning point in her familiarity with the language of protest.

The CM’s apprehensions are understandable. Whether in power or in Opposition, it is in her role as the underdog that Banerjee has been most at ease. Over the past four decades, she has positioned herself again and again as the counterforce to the establishment even when she is the establishment. In a party which runs on the cult of Didi, notwithstanding her autocratic tendencies, it has stood her in good stead, especially outside of the state capital. This even when her administration’s grasp on law and order has appeared to be slipping, even when a string of corruption cases — from the Saradha scam to the recruitment scam — have mired her party functionaries, even when complaints of sexual harassment and police inaction have come up in Sandeshkhali. In June, for instance, Banerjee berated her ministers, bureaucrats, police and other functionaries for systemic corruption, giving out the signal that she stood apart from her partymen.

A large part of Banerjee’s charisma owes itself to this ability to distinguish herself from others and leverage her working-class background. In the Left Front government’s over three-decade rule in Bengal, politics had been the bastion of the bhadralok, its leaders belonging to the middle class, a euphemism for socio-economic and cultural capital. Jyoti Basu, chief minister between 1977 and 2000, was a barrister, an alumni of premier institutions. Buddhadeb Bhattacharya was known for his interest in and knowledge of movies, theatre and literature. In contrast, Banerjee came up from the trinamool — the grassroots — and propped herself up as an everywoman fighting her way through life. The second of seven siblings, her education and upbringing were modest. In speech and attire, she has rejected the template of the genteel; her poetry and painting can be called pedestrian at best. But what Banerjee recognised much before her political opponents was the power of a spectacle and the role of the media in amplifying it: She offered her story both as rebellion and alternative. Her emotional outbursts, pushbacks against attempts to hem her in, targeted welfare schemes lent her a folk appeal as a champion of the masses, articulating their aspirations and grievances. By the time the Singur and Nandigram movement took shape in 2007, Banerjee had cemented her base among the state’s agrarian population. When she came to power in 2011, she had managed to convert a large section of the urban intelligentsia — the buddhijibis — in her favour.

Why did Banerjee fail to read the signs this time? In the immediate aftermath of the gruesome incident, her government’s missteps speak of a tentativeness — a nervous tic even, to maintain status quo unless pushed otherwise — that is an administrator’s inheritance. It also signals the complacency of a government and party that has been in power for over a decade, arrogant in its assumption of its own irreplaceability. But most of all, it speaks of an inability to read the disruptive heft of a disappointed people whose ease with the media outdoes the CM’s own, who can measure out their lives in reels and live streams, whose legitimate demand for punishment and justice must not only be met but be seen to be met.

Banerjee failed in the opening gambit. Her subsequent attempts at breaking the impasse have not succeeded at the time of writing. Can she turn the corner still?

paromita.chakrabarti@expressindia.com