With Ratan Tata’s passing, India has lost a great institution builder and leader. Ratan Tata brought a flotilla of independent companies to move together to the same vision of a globally competitive Indian industry built by Indians, powered by the same humanistic values that Jamshedji Tata, the founder of the group in the 19th century, had inspired. Mahatma Gandhi said that while he was fighting for India’s political freedom, Tatas were fighting for India’s economic freedom.

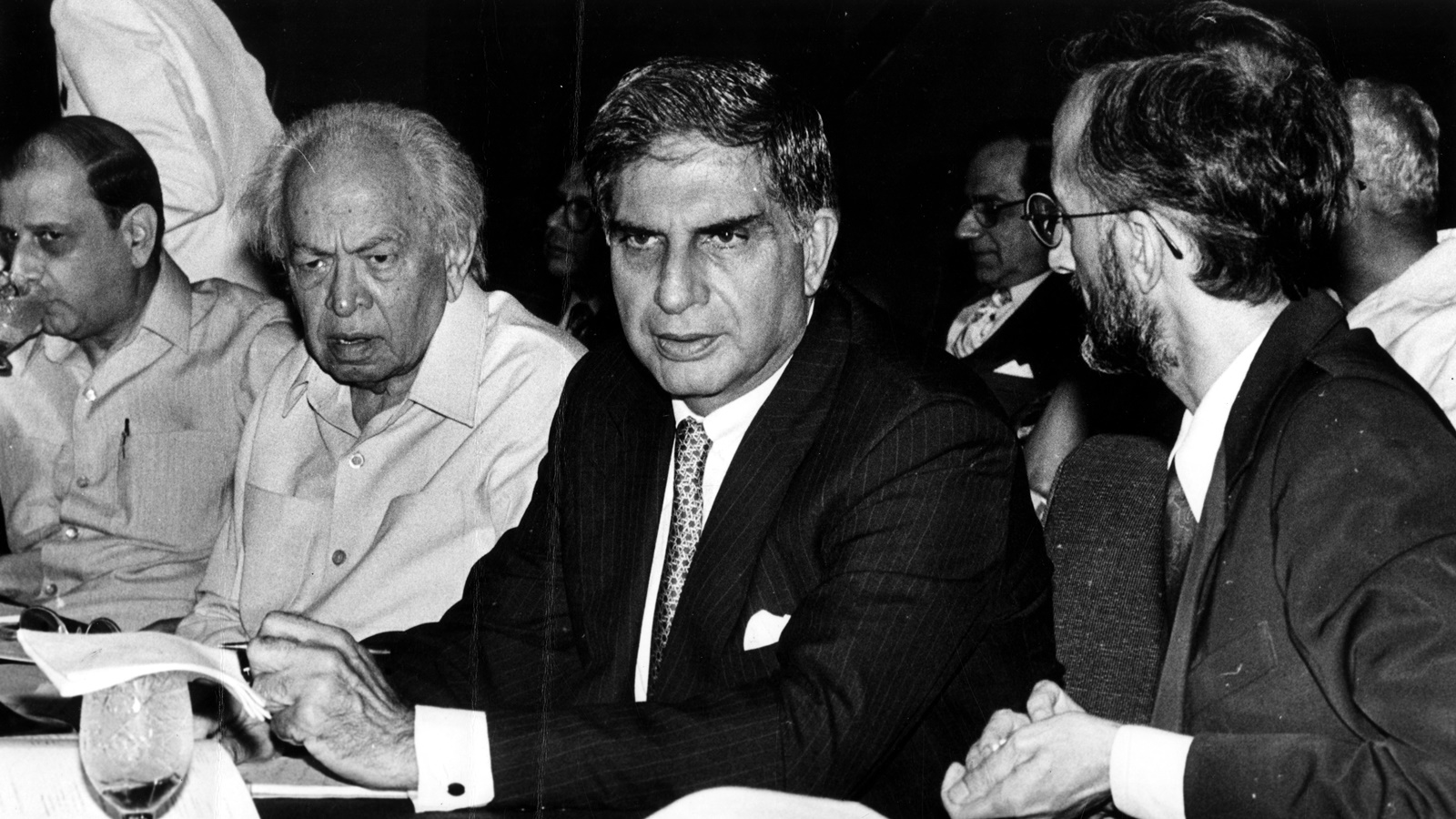

J R D Tata, Chairman of the Tata Group during the difficult post-Independence years when new foundations were being built for Indian industry, had to make many difficult decisions. Whenever there was a dilemma between what was good for Tatas and what was good for India, he said he would always choose the latter. In the long run, it would turn out good for Tatas too, he said.

Tatas was the largest, and most diverse Indian conglomerate in JRD’s time, as it is now. The Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission determined conglomerates concentrated too much power with their promoters. In 1969, it broke up the managing agency system with which promoters of conglomerates controlled their companies. The Commission recognised that Tata’s values were different to the others, but the law had to apply to all. J R D. Tata had to stop the practice of CEOs of Tata companies meeting together every week with the Group Chairman to share best practices and information about the economy. Thus, the Tata flotilla drifted apart with independent leaders guiding their own companies. Ratan inherited this arrangement from JRD in 1991.

Management theorists say conglomerates are too complex to manage. Stock markets see conglomerates as value destroyers. Investors have compelled their breakup to release financial value. Going against this global trend, Ratan devised an institutional architecture to bring the Tata flotilla together while maintaining all company boards’ independence. He created new, lateral linking platforms below board levels, where executives could learn new ideas and best practices together about the management of quality, development of human resources, and stimulation of enterprise innovations, which would be consistent with Tata values. The boards of companies signed agreements with Tata Sons to comply with Tata values for their right to use the Tata brand, which was a hallmark of trust in India, and very valuable for hiring employees, acquiring customers, and raising finance.

When I joined the Planning Commission as a Member in 2009, the Prime Minister, Dr Manmohan Singh, gave me a special task. Citizens’ faith in the government’s ability to produce outcomes was low. Business corporations were mistrusted for being in it for themselves and their shareholders only. Loss of trust in institutions was a global trend. The Edelman Trust Barometer reported that governments and business corporations were amongst the least trusted institutions everywhere. Moreover, a central Planning Commission was seen as an outdated, top-down, way of managing a dynamic economy. The PM asked me to reflect on a new role for the Commission and consult my friends in the business world too.

Ratan and I had joined Tatas around the same time in the 1960s. We were colleagues and friends. We travelled together to learn. I had trusted Ratan, when he was a novice pilot, to fly me in single-engine Tata planes from Jamshedpur to the company mines and collieries, sometimes in stormy weather, while he was completing his number of flying hours to qualify for a pilot’s licence. I turned to Ratan for ideas on the Planning Commission’s role in aligning the federation of Indian states and independent businesses to make India a country good for all its billion citizens. My questions were: How can a central body which does not have financial control add value? And how should it guide captains of independent ships in a flotilla?

Ratan used an analogy of a pilot flying an aeroplane in bad weather guided by a radar system. Radar-based systems scan the environment. They notice signs of bad weather and all planes in the sky. They recommend paths for pilots who have responsibility for the safety of their passengers. Pilots use this information to make their decisions. He recommended that the Planning Commission use the methodology of scenario planning instead of relying on detailed plans and budgetary controls. It should also set up learning forums on subjects of national interest, such as education, public health, and skill development, in which all states and even businesses could participate to learn together.

The Planning Commission applied scenario planning as an add-on to the legacy, expert and numbers-driven planning process when it prepared the 12th Five-Year Plan for “more inclusive, sustainable, and faster growth”. Three plausible scenarios emerged for India’s future. They were titled, ‘Muddling Along’, ‘Falling Apart’, and ‘The Flotilla Advances’. ‘Muddling Along’ described the confusions in India’s economic strategy then, which persist even today. Make in India or not? More government in education and health or more private? More regulation of industry’s impact on human beings and the environment, or reduction of regulations to make it easier for businesses to make profits?

Sadly, with the dismantling of the Planning Commission in 2014, insights from the scenarios were also lost. These insights will enable the Indian flotilla to advance as one country towards one destiny. Otherwise, internal divisions, between haves and have-nots, between ethnic, caste, and religious groups, and between political parties vying for power, can tear the union apart.

More GDP is not producing good employment and adequate incomes with social security for the masses, even those with higher education. Even upper castes want reservations for jobs. Natural infrastructure is being destroyed with excessive and misplaced concrete infrastructure. Hillsides are collapsing; water bodies are disappearing; rivers are polluted; cities are choking; fertile soils are degrading. The pattern of ‘jobless’ and nature-destroying growth must change.

The scenarios recommended a new architecture for the governance of the country and a framework for guiding economic policies:

- Inclusion through faster growth of livelihoods instead of more handouts and subsidies

- Sustainability through community-based solutions instead of large projects

- More localised governance instead of centralised control

- Rather than chasing GDP, the Indian government should apply this framework of governance. It is consistent with Ratan Tata’s philosophy for governing complex systems. Thank you for being a national role model, Ratan.

The writer is Chairman, HelpAge International and former member, Planning Commission