Dec 23, 2024 17:26 IST First published on: Dec 23, 2024 at 16:06 IST

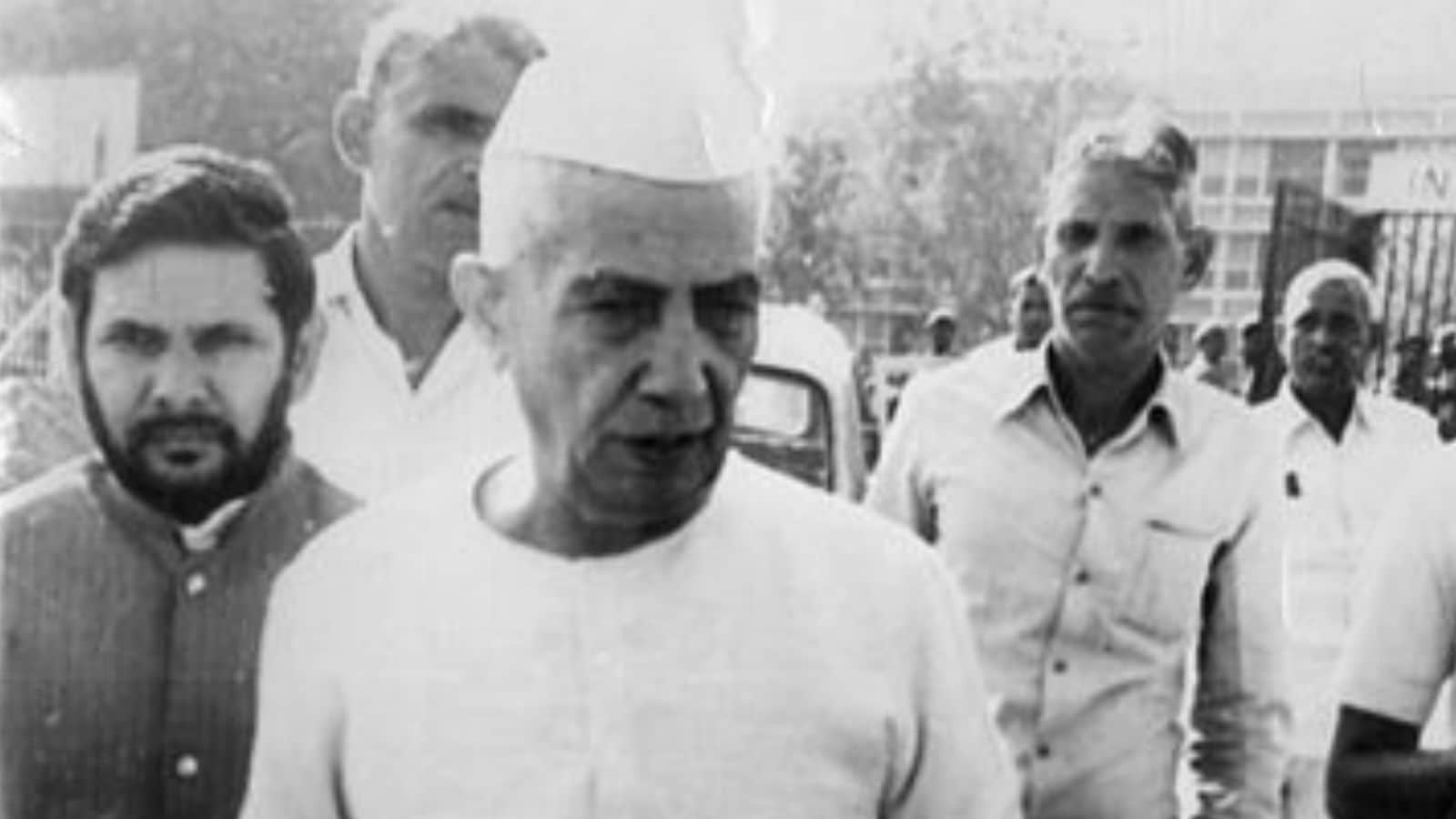

As issues of farmers and social justice dominate our nation’s politics, it is worth remembering the enduring legacy of the late former Prime Minister Chaudhary Charan Singh (1902–1987) on his birth anniversary. During his lifetime, Charan Singh championed the cause of peasants, small producers, and backward castes, empowering their voices and institutionalising their presence in politics and public services long before the Mandal Commission put things on paper. Remembered for his unwavering support for farmers and land reforms, Charan Singh also shaped the politics of social justice in post-colonial India. The present-day demand for a caste census has renewed the debate on reservation, and the charge by the opposition parties that the current BJP-led government might alter the Constitution to weaken reservation has acquired a political heat. Charan Singh’s life and views might offer a way out of this political quagmire.

Farmers’ rights as a path to social justice

Born in a peasant family in UP in 1902, Charan Singh grew up witnessing the exploitative effects of the zamindari system. As he grew up, he associated himself with Gandhian mass nationalism and principles. The Gandhian influence of Charan Singh led to him Khadi and becoming an advocate for the welfare of small producers and agriculturalists. His rise as a peasant leader in late colonial India was not delinked from the larger national anti-colonial politics, which considered peasants as a key mobilising force against foreign rule. Singh became a part of the Congress early in his life, and when the Congress formed the provincial government in the United Provinces in 1937, he was one of the legislative representatives. In postcolonial India, he became a parliamentary secretary (junior minister) and later the Revenue Minister in the UP government. During this period, he shaped the Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Bill, which became law in 1952. By making landless tenants and sharecroppers owners he redistributed the land of those he considered the parasitic class of landed elites (the zamindars).

Land redistribution changed the agrarian landscape and power hierarchy of modern India in unprecedented ways by giving land ownership to backward castes, including the SCs. However, his concern for peasants did not stop at land reforms. It extended to the realm of social justice, centring around the entry of socially and economically backward peasants into government jobs, freeing peasants from the clutches of moneylenders, and ensuring education.

He identified peasants as a marginalised social group that had been left out of public service employment. His understanding of the peasantry’s backwardness is mediated through an understanding of space and caste. Early in his political career, he proposed a 60 per cent reservation for farmers’ children in government jobs and educational institutions. Though the percentage and format in which this demand was placed kept changing, his rationale for pushing the peasantry into mainstream national politics was premised on his understanding that agriculturalists contributed over 80 per cent of the state’s revenue. Charan Singh viewed the neglect of rural India as a class conflict between urban elites and the agrarian majority.

The language of class and space at the same time allowed Singh to target the wealthy elites, residing both in the countryside and in urban areas. He observed that the educated urban elites often looked down upon rural communities and used contemptuous remarks that echoed colonial prejudices. “The urbanite considers himself superior to the farmer”, Singh lamented. In 1961, Singh conducted a groundbreaking study that revealed stark inequalities in government employment. While just 11.5 per cent of civil servants came from farming families, nearly half had urban and government service backgrounds. This reinforced his belief that systemic interventions, such as reservation, were necessary to correct these imbalances.

An advocate of equal opportunity

Chaudhary Charan Singh was among the earliest leaders to defend reservations. He countered arguments that reservations undermined meritocracy by highlighting the structural inequities that denied backward classes access to quality education and opportunities. “Equality can only be meaningful when everyone has access to the same resources,” he argued, pointing out the hypocrisy of judging marginalized groups by the same standards as privileged ones.

The late 1960s and 1970s marked a turning point in Singh’s political career and ideas. He moved out of Congress, founded his political party, the Bharatiya Kranti Dal (BKD), and became UP’s Chief Minister for two brief spills. Aligning with socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia, he refined his understanding of categories that should get a reservation, mainly excluding the traditionally privileged Dwij castes, in line with the broader category of the backward classes. This shift underscored his focus on addressing deep-seated caste inequities within the homogenous category of peasants. The BKD manifesto of 1973 proposed to implement a 25 per cent reservation for Backward Classes in government-gazetted jobs as per the recommendations of the 1959 Kaka Kalekar Backward Classes Commission.

During his tenure as the Home Minister in the Janata Party Government (1977-1979), Singh oversaw the formation of the Mandal Commission under B P Mandal, which later provided a detailed framework for affirmative action policies. When the Janata Party government coalition failed, Charan Singh became the fifth Prime Minister of India in July 1979 with the support of Congress. His tenure was short and he remained a caretaker Prime Minister till January 1980. While in power and in the midst of elections, he proposed to implement a 25 per cent reservation for OBCs in central government services. The proposal failed, as his powers as PM were only one of a caretaker. Though Singh could not see the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, his efforts were critical in legitimising the demand for reservation for backward classes.

most read

Legacy of social justice

Charan Singh’s legacy as a leader of peasants and the downtrodden, more than just as “a peasant leader”, asks us to see peasantry as a differentiated mass that inhabits layers of inequalities within itself as well as in relation to elite city dwellers. His focus on meeting the challenges of systematic inequalities across rural and backward communities through reservations affirms the relevance of today’s social justice politics. The electoral demand to homogenise the rural population did not stop him from raising issues of layered backwardness within the world of the rural.

Vikas Malik is an Assistant Professor at Shyama Prasad Mukherji College, University of Delhi. Arun Kumar is a historian based in Nottingham

Vikas Malik is an Assistant Professor at Shyama Prasad Mukherji College, University of Delhi.

Arun Kumar is a historian based in Nottingham

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package