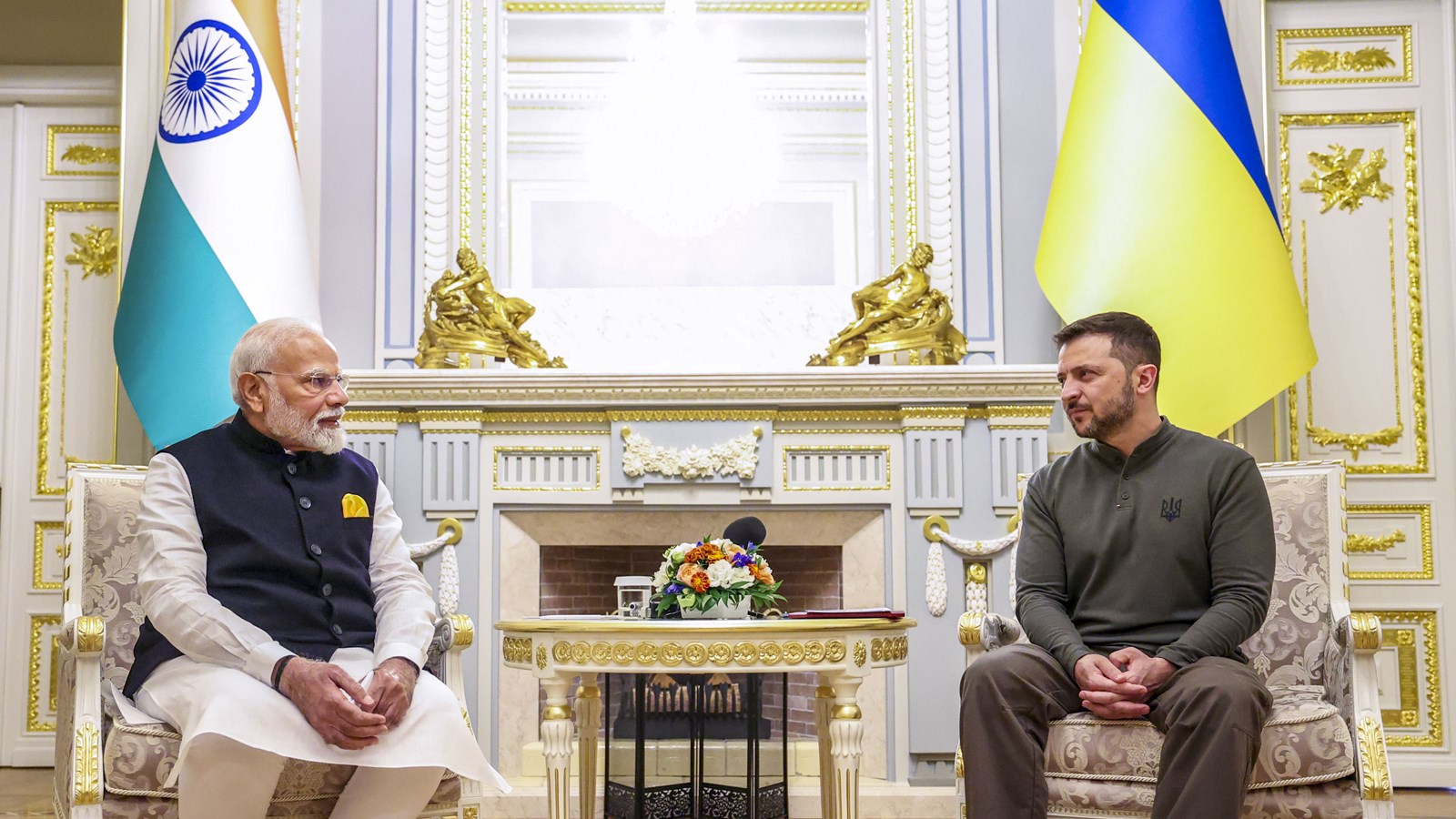

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi embarked on the train journey from Warsaw to Kyiv, the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount perhaps best captured his noble venture. Jesus said, “Blessed are the Peacemakers: for they will be called the children of God”. (Matthew 5.9) Modi is one of the few international leaders to have visited both Moscow and Kyiv. He has constantly advocated the path of diplomacy and dialogue to end Russia’s Ukraine war. Indeed, Modi told Putin, in a face-to-face meeting in Uzbekistan, in September 2022, that this was not an era of war. This was as unequivocal, though indirect, expression of disapproval of the Russian action as possible; especially, as it came from a leader who has to look to his country’s interests even as he wishes for peace and upholding international law.

The dichotomy between PM Modi’s desire for peace and justice in Ukraine and the compulsions of India’s deep interests in Russia has been witnessed since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These constraints can be once again be seen in the India-Ukraine Joint Statement on his visit to Kyiv.

Consider: In the section entitled “Ensuring a Comprehensive, Just and Lasting Peace”, paragraph 6 notes “Prime Minister Modi and President Zelenskyy reiterated their readiness for further cooperation in upholding principles of international law, including the UN Charter, such as respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty of states. They agreed on the desirability of closer bilateral dialogue in this regard”. Paragraph 7 reinforces India’s commitment to international law. It states “The Indian side reiterated its principled position and focus on peaceful resolution through dialogue and diplomacy, as a part of which, India has attended the Summit on Peace in Ukraine, held in Burgenstock, Switzerland, in June 2024”. These are formal and “de-jure” positions held by India.

Modi clearly abandons these de-jure formulations and the quest for “Comprehensive, Just and Lasting Peace” when he goes for the possible and practical to end the war in paragraph 11: “ Prime Minister Modi reiterated the need for sincere and practical engagement between all stakeholders to develop innovative solutions that will have broad acceptability and contribute towards early restoration of peace. He reiterated India’s willingness to contribute in all possible ways to facilitate an early return of peace”.

The last sentence of paragraph 11 is a clear indication of India’s willingness to get involved in a search for peace in Ukraine. It is here that the Indian foreign policy establishment needs to make a realistic assessment if Ukraine and its Western partners want India to go beyond effectively pressing Russia to reverse its aggression.

They obviously want India, as Zelenskyy said, to stop buying Russian oil so that it feels economic pain. It is doubtful if External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s articulations of reasons which have led India to purchase Russian oil cut any ice in Kyiv. It clearly believes that India can do more to impress upon Putin to reverse the steps he undertook in February 2022.

There is a historical parallel going back four decades to what the West and Ukraine want of India at this stage. That parallel lies in the situation which arose in Afghanistan following the Soviet intrusion in that country on Christmas Eve of 1979. India was deeply unhappy with the Russian action but like now, then too, it did not publicly criticise Russia. By the mid-1980s, as India’s ties warmed up with the US and as it became clear that Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev wanted to withdraw from a “bleeding ulcer”, the US urged Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to use his influence on Russia to hold firm to its intention to withdraw. However, when India wanted a say in a post-Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, it virtually told India to lay off.

The Ukraine war has impacted the Global South adversely and it has international geopolitical implications involving the US and China. However, at its core, it is a European war. It has upset the European security architecture. While there is no doubt that the present era is fundamentally different from that of the Cold War and that India too has fundamentally changed economically and in terms of power projection, the question is whether the Western powers and Ukraine want a meaningful Indian intervention or initiative in seeking peace. Some Indian analysts appear to think that this may be so. However, Zelenskyy’s public observations do not offer any such indication.

The fact is that on the Ukraine issue, the US and its allies on the one side and China and Russia on the other have locked horns. Ultimately it is they that have to unlock them. Do they see a role for other powers, including India? There is nothing to suggest that they want India and others to do anything but condemn Russian action and apply economic pressure.

Modi is the first Indian Prime Minister to visit Ukraine. The fact is that Indian-Ukraine relations got off to a bad start. It is now perhaps forgotten that Ukraine supplied Pakistan with over 300 T-80 battle tanks over India’s strenuous objections. Ukraine was also one of the few countries to have used the word “condemned” for India’s nuclear tests of 1998. Naturally, this cast a long shadow over the relationship. It can be argued that these should not have been allowed to have a long-term negative impact on bilateral ties but then India’s response to Russia’s Crimea action also inhibited an effective growth in ties.

The writer is a former diplomat