Ask for trivia involving the history of Indian chess and it is entirely possible that the answer invariably points in the direction of Viswanathan Anand. He is, after all, the man who became the first grandmaster from India, was the first Indian to win the World Junior Chess Championship, became the first senior world champion from India, and is the first Indian to be World No 1.

But there was one feat that another Indian chess player achieved long before Anand had the chance to. At the 1980 Olympiad in Malta, when Anand would have been just 11 years of age, Mohamed Rafiq Khan bagged India its first-ever medal — a silver — on the third board at the Chess Olympiad.

The Chess Olympiad, first held in 1927, is the most prestigious event for national teams in the sport. It is a collective flexing of the muscle in a sport that is largely individualistic. Any nation can luck out and discover one star with the potential to become the world champion. But to win Olympiad medals, you need at least three players of exceptional ability. The unique format of the Olympiad means that every nation designates players on the four boards, with the top board players usually being the strongest player in the team. And while the Olympiad is a team event, there are also medals for each individual board.

Both the current Indian teams at this year’s Olympiad in Budapest, which started on September 10 and ends on September 23, in the open and the women’s sections — are stacked with world-beaters and are likely to return home with medals. If they do, it will be a coming-of-age moment for Indian chess, which started sending teams to the Olympiad from 1956. Almost all of the 10 players competing for India at the Budapest Olympiad have similar stories in the sport: they had access to cutting-edge technology, like chess engines, and got coaching from elite grandmasters very early on in their tryst with the sport.

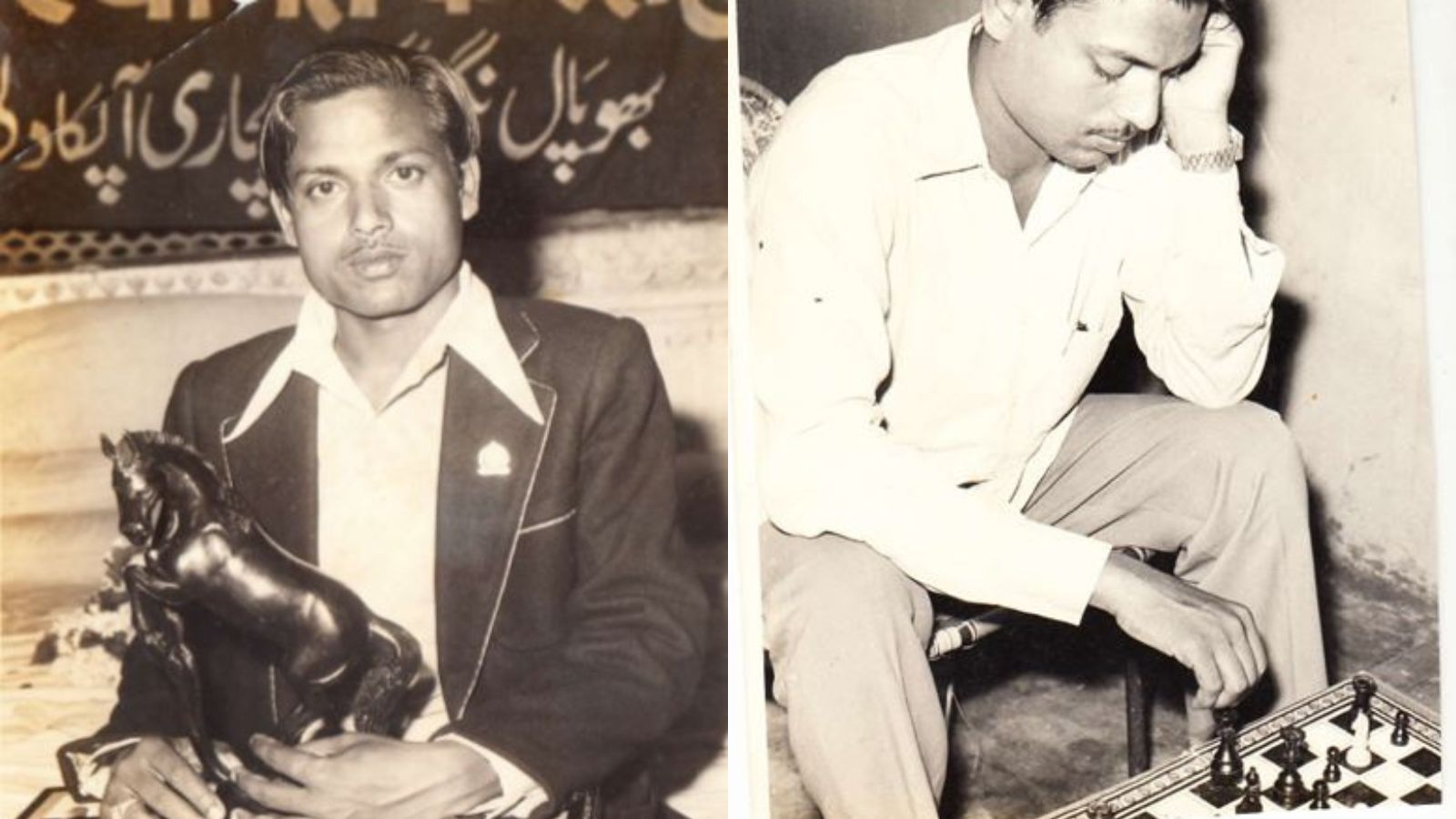

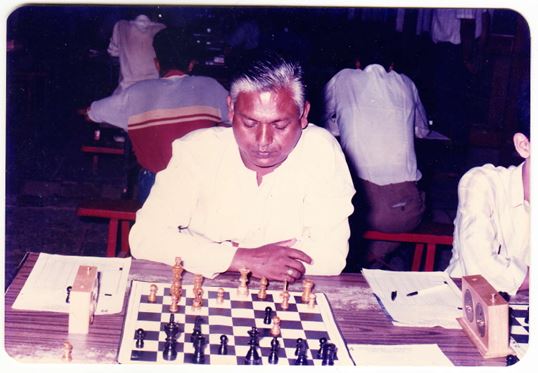

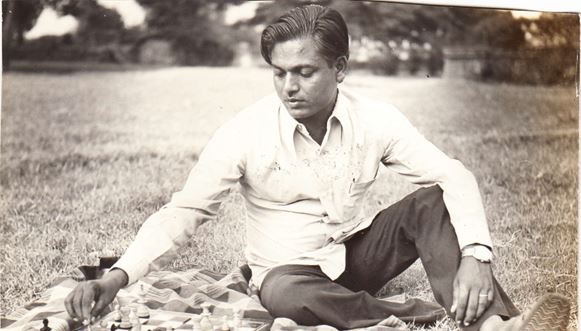

This is what makes Khan’s story stand out even more. He was a carpenter who fell in love with chess after learning the sport on the patiyas of Bhopal. Patiya is slang for a slab of stone or wood that is placed in front of tea shops or the verandahs in front of homes in Bhopal.

Starting his tryst with chess as a patiya player, Khan never became a grandmaster or even an international master — the top two titles chess players can hope to achieve. However, his kind heart and skills on the chessboard did earn him the respectful moniker of Ustaad on Madhya Pradesh’s chess scene.

The form of chess that Khan learnt on the patiyas of Bhopal was a slightly different version of international chess: in desi chess, pawns could only move one square ahead as compared to the modern game, where pawns can jump ahead two squares with their first move. But that mattered for little when he played competitively. Khan won the state championship the first time he competed in it. Back then, there was a two-tiered national championship in chess: National A and National B. Players who did well in National B would make the cut for National A. Playing in the National A back then was a matter of prestige.

“Rafiq ji had what you would call a natural talent. He could not read any chess books because books back then would exclusively be in English or Russian. And he was not educated. Despite that, he was a formidable player. His game play was very practical. Not knowing how to read chess books meant that he had very little theoretical knowledge, so he would not do well in the openings. But he would make up for it in the middle and end games,” Akshat Khamparia, Madhya Pradesh’s first International Master, who is now a functionary in the Madhya Pradesh Chess Association, tells The Indian Express.

“As a person, despite the heights his game reached, he was very down to earth. He was Madhya Pradesh’s first FIDE Master. A genius. If he had received support in those days from the state association, he could have become our first grandmaster. The state still does not have one. He was grandmaster material,” Khamparia adds.

Having known Khan, who died in July 2019, Khamparia says that for many Madhya Pradesh players, Ustaad was a resource in the pre-computer days of chess. “Now you have computers that feed you the best moves. But back then, you had to calculate everything yourself. This was the age of classical games being adjourned, when players would come back and resume the game the next day and would spend the night plotting their play ahead. He would be of great help to any player from Madhya Pradesh in those days. People would keep him awake all night as they huddled over the board and tried to figure out their next moves,” says Khamparia.

The silver medal at the Malta Olympiad aside, Khan’s most memorable exploits on the chessboard involved defeating Belgian chess player Albéric O’Kelly de Galway twice by using the O’Kelly Sicilian, a chess variation in the Sicilian Defence.

What was so remarkable about those two wins? The defeats were remarkable because a patiya player from Bhopal defeated a Belgian master by using a variation named after the latter, who was one of the foremost exponents of the move.