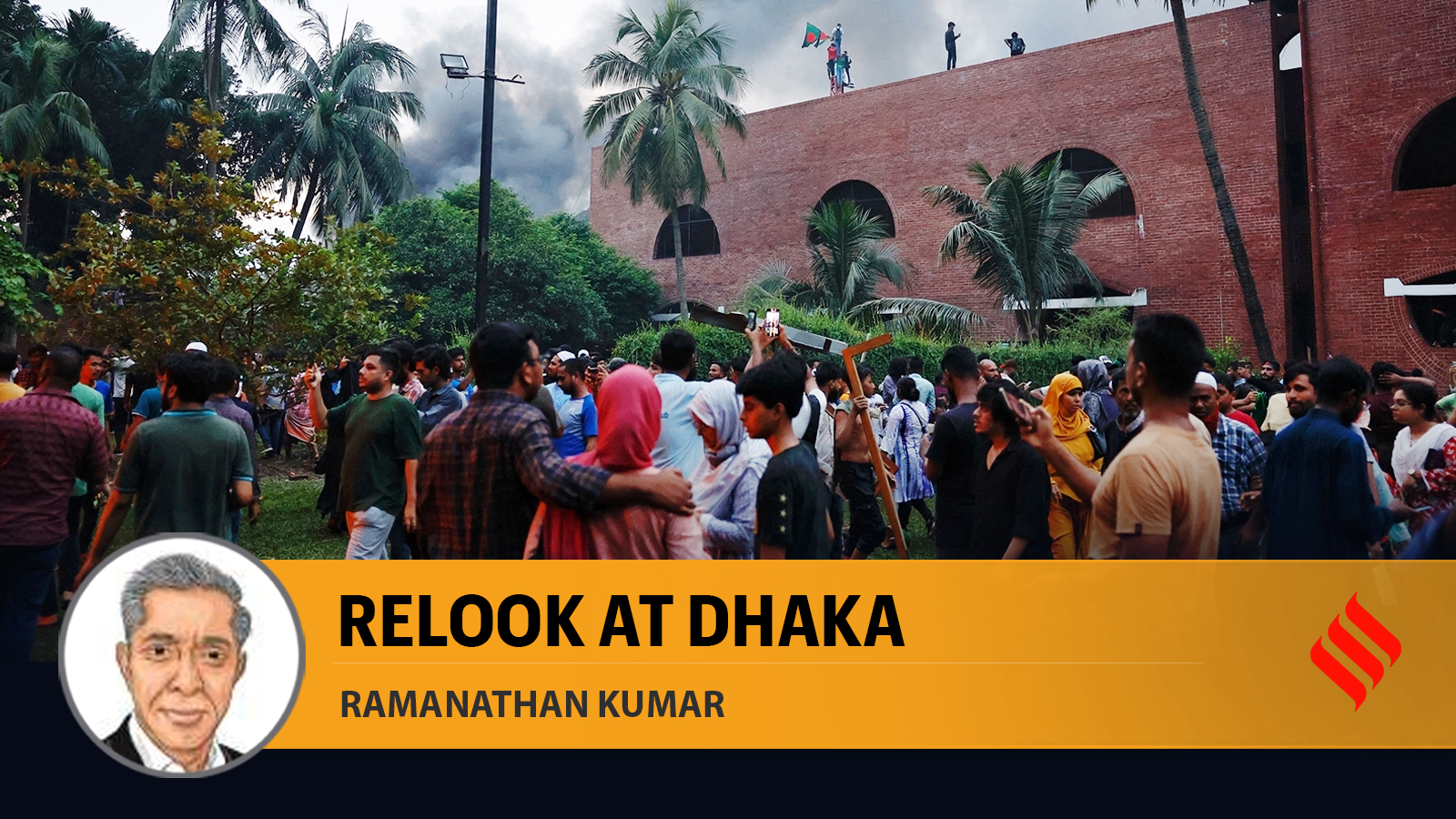

The ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in a mass upsurge of “people’s power”, and the assumption of power in Dhaka by an interim government headed by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus is, doubtless, a watershed moment in Bangladesh’s tumultuous history. As many have pointed out, it is a moment that holds both peril and promise, calling for a measured and sagacious response from all those who have a stake in regional stability.

For close to 15 years, in stark contrast to the preceding years, the use of Bangladeshi territory was effectively denied to all manner of terrorist and insurgent organisations and their backers who were eager to do India harm. This decisive transformation would not have been possible but for the concerted efforts of the government that was in power in Bangladesh during this period and the mutually beneficial cooperation between the concerned institutions of both countries. These are incontrovertible realities that no government in New Delhi can be oblivious or indifferent to.

In accordance with the well-established principle of non-interference, it has been India’s long-standing policy to refrain from passing judgement on what are essentially internal political matters of other countries. Bangladesh has been no exception in this regard. Those who espouse the view that, given India’s perceived proximity to — and influence over — key decision makers in Dhaka, we could somehow have influenced the course of Bangladesh’s internal politics during the years that Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League were in power would do well to keep this fundamental limitation in mind.

For the last decade and a half, Bangladesh and India have, by and large, lived peacefully as neighbours, unburdened by the rancour and recrimination that was a defining characteristic of their relationship for much of the past. The outcome has been the healthy blossoming of ties in a multitude of areas, ranging from security to multi-modal connectivity to trade and commerce to infrastructure development and people-to-people contact. More than 15 lakh Bangladeshi nationals travel annually to India for a host of purposes ranging from tourism to business and medical treatment. Bilateral trade rose to $18 billion in 2021-22. Cooperation in the power and energy sector, once unthinkable, has become an important pillar of the bilateral relationship, with Bangladesh currently importing as much as 1,160 MW of power from India. The potential for further progress in all these areas — and more — is nothing less than immense.

The remarkable progress made by Bangladesh in many indices of socio-economic development, such as literacy, infant mortality, women’s empowerment and financial inclusion is acknowledged and respected by many in India. The success achieved by Bangladesh’s garment industry has been lauded and sought to be replicated by business enterprises in India. The concept of microfinance, pioneered by Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank, has been embraced by several Indian institutions.

This is not to romanticise the recent past or to assert that everything has been perfect between India and Bangladesh. India has made every effort to reciprocate Bangladesh’s contribution towards alleviating its security concerns, but dismay persists among sections of Bangladeshi civil society over the issue of the killing of Bangladeshi nationals at the borders by Indian security forces, despite India’s effort to bring down the number of such casualties. The matter of equitable sharing of river waters, which assumes overarching priority for Bangladesh, defies easy resolution, not least on account of India’s burgeoning needs. Finding lasting solutions to these complex problems remains a work in progress, but given political will and perseverance, they can and will be resolved to the satisfaction of both sides. Mutual recrimination and whipping up negative sentiment over contentious issues cannot be the answer.

The anarchy unleashed by the fall of the previous regime has, understandably, brought to the fore concerns about the prospects of Bangladesh being engulfed by the winner-takes-all brand of politics that it has experienced in the past; by religious fanaticism and by the cross-currents of untrammelled geopolitical rivalry among major powers. These are concerns that cannot be taken lightly by the decision makers, opinion shapers and people of Bangladesh or by those of other countries in the neighbourhood and beyond.

At a time when new social and political forces are rapidly emerging in Bangladesh, the young student leaders who spearheaded the movement for political change and their supporters should bear in mind that millions of ordinary Indians share the developmental aspirations of their counterparts in Bangladesh and wish them well in their endeavours. Endemic poverty, mass unemployment among youth, runaway inflation, climate change, environmental degradation and the spread of infectious diseases are some of the all-pervasive enemies that respect no borders and stalk the people of both countries. It goes without saying that these common challenges can only be addressed in a spirit of mutual cooperation rather than one of hostility and mistrust.

India and Bangladesh must face the future with renewed hope and confidence, eschewing the perils and embracing the promise of the fundamental reset that has taken place in Bangladesh. A reversion to the nay-saying and finger-pointing of yesteryears is not an option.

The writer, a former special secretary in the Research & Analysis Wing, served in Bangladesh. Views are personal