Most of the

wheat

has arrived in the

mandis

of Punjab and Haryana, the two states with the highest

procurement

. And by all accounts it’s a good

crop

, providing much needed comfort to govt and

private players

.

The crop, which comes on the back of a good yield this year – as high as 25-26 quintals an acre in parts of Punjab (against 22 quintals or so last year) – is much watched given that silos emptied out after two years of poor harvest.

Govt is grappling with the lowest level of wheat stocks in 16 years – a little over 75 lakh tonnes at the start of April against the buffer requirement of 74.6 lakh tonnes for this time of year – and globally, too,

prices

are under pressure.

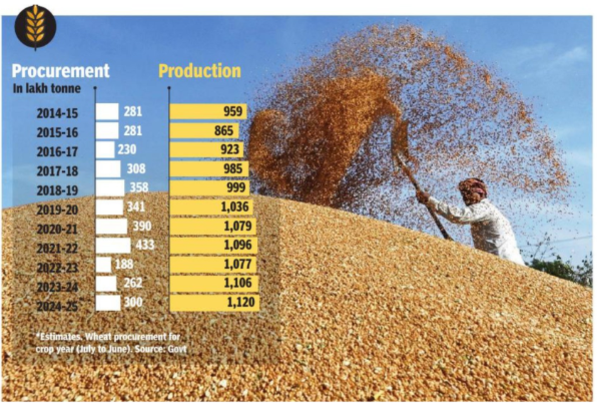

So far, govt procurement is estimated at 200 lakh tonnes, compared with 190 lakh tonnes at the same time last year. In Punjab, the prolonged winter has resulted in around 91 lakh tonnes reaching mandis so far, compared with 103 lakh tonnes at this time last year.

“We are seeing the best crop in at least five-six years,” says Manjinder Singh Mann, secretary of Khanna Agricultural Produce Market Committee.

New Seed Varieties

In Karnal, Gyanendra Singh, director of ICAR-Indian Institute of Wheat and Barley Research, lists out multiple reasons for this year’s bumper crop, which he argues may beat govt estimates. “The area under cultivation has increased, we had a good winter, which was prolonged and there has been accelerated deployment of climate resistant varieties. Nearly 60% of the varieties were released during the last five years.” New varieties are less prone to damage by pests, something that farmers in the two states are reporting.

At the FCI headquarters in Delhi, officials reckon that govt procurement could reach 310 lakh tonnes, against 262 lakh tonnes last year, based on higher purchases in most parts – from Punjab and Haryana to Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. While Punjab is going to remain on top with purchases of over 130 lakh tonnes (121 lakh tonnes last year), Haryana is estimated to generate 70 lakh tonnes this year (against last year’s 63 lakh tonnes). FCI officials are banking on a 10-fold jump from UP to around 20 lakh tonnes as govt purchases currently are estimated at 3.4 lakh tonnes, compared with last year’s 5.6 lakh tonnes. They are also estimating a threeto four-fold increase in Rajasthan, from around 4 lakh tonnes to nearly 12-14 lakh tonnes. MP remains a source of bother, although the target is to buy around 80 lakh tonnes, compared with 71 lakh tonnes last year.

Private Purchase Zooms

But it isn’t just govt agencies that are buying whatever is reaching the mandis, private players are ramping up their stocks too.

In Khanna, once the largest grain market, around 40% of the purchases may end up in private hands. In neighbouring Rajpura, which also sees robust trading, more than half the stock brought to the mandi has been purchased by flour mills, some of whom sell to big players, such as ITC, Adani and Nestle.

Davinder Singh, president of the arhtia association in the APMC, estimates that of the 25 lakh bags of 50kg each, private players will this year buy around 10 lakh. Last year, they had bought 4.5 lakh of the 22 lakh bags in the mandi, and in 2022, two lakh of the 14 lakh bags.

In Gharaunda and Karnal, two mandis in Haryana that TOI recently visited, private demand is strong.

While private players have been present in the grain market, and their share of total purchases is rising, this year is different. “The govt does not have too much stock, so we don’t know if it will undertake open market sale this year, something it did actively last year,” said Atul Goyal, of Amar Roller Flour Mills, a large buyer from Rajpura.

There is also expectation of prices rising in the coming months. Against a price of Rs 2,280 a quintal for private players at the moment, prices for June are around Rs 2,450 and may rise to Rs 3,000 by Oct, says Singh. Against procurement of just under one lakh tonnes of wheat in Khanna, in 2023, Rajpura reported purchases of over 105 lakh tonnes. One of the reasons for higher private purchases in Punjab may also have to do with state govts in MP and Rajasthan deciding to pay a bonus of Rs 125 a quintal a

bove the Centre’s minimum support price of Rs 2,275 a quintal, resulting in some trade moving out.

In any case, arhtias – the middlemen who run the show in mandis in Punjab and Haryana and were seen to be the key driver of the farmers’ protest when govt had decided to amend the farm laws – prefer private sales as they earn Rs 57 a quintal, compared with Rs 46 from govt. Besides, the payment comes on the same day, while they have to wait for the end of the season with govt procurement.

For farmers in this part of the country, arhtias are the crucial link, often providing loans during marriages or emergencies. Of course, direct payment into bank accounts has meant that cash flows to the farmers within three days in Haryana and in around a week in Punjab.

“The system favours us now. Now, arhtias have to ask us for money, instead of them deducting the money and paying us,” says Sukhbir Kumar, a farmer selling his produce in Gharaunda.

Diversifying Markets

For years, farmers from adjoining areas in Uttar Pradesh, or even distant Bihar, would see their produce sold in mandis in Haryana and Punjab. But with UP govt deciding to aggressively push procurement, Karnal is seeing fewer farmers drive past the state border.

Ram Pal Singh from Shamli is one of the exceptions. He has driven past police barricades at the border to sell his 80 quintals of wheat to arhtias, settling for cash payment. “I have been coming here for more than 30 years. The mandi on our side does not have facilities like here,” he says, smoking a bidi at a tea stall as he waits for the grains to be cleaned.

Ramesh Yadav from Madhepura is part of the thousands of workers who travel to Khanna every year. He has already harvested 20 quintals of wheat in his village, selling a part of it at lower than MSP. “The maize (which has also been sold below MSP) will travel to Punjab and fetch 10-15% more,” says Yadav as he breaks for lunch after spreading the wheat to dry in Khanna.

Moving Away From Paddy

“No one in this part of the country eats parmal rice that is procured. It is either distributed in the poorer states or supplied for mid-day meals or in jails,” says the secretary of one of the APMCs in Haryana.

But farmers still prefer to grow paddy as the state machinery purchases it at the MSP, shielding them from price fluctuations. While Haryana govt procures some amount of mustard and sunflower seeds, it isn’t enough.

“Last year, I sold maize below MSP. In my fields, I may not be able to grow urad or mung,” says Kawaljit Singh in Karnal.

Standing a few metres away, Roshan Lal, who tills around 30 acres to grow wheat, paddy and potatoes, acknowledges the problem with paddy. “ I grow paddy because I get MSP. With maize the yield is good, it requires lower amount of water, fertiliser and pesticides, but I may not be able to sell it,” says Lal, who complains of low income for farmers and intends to migrate to the US in a few years to join his son in California.

In Punjab the problem is even more acute as there is no govt procurement, farmers said.

“The water table has gone down, now we find water at 150 feet, compared with 100 feet five years ago. I know there is a problem and it will only increase. I can try other crops such as dal, maize or mustard, provided there is assured procurement,” says Harinder Singh from Channi Majra village near Khanna.

When farmers in Punjab hit the streets earlier this year, Centre had suggested it could guarantee procurement of maize, pulses and cotton for five years to farmers who diversified from paddy, a key source of pollution in north India post-Diwali due to stubble burning. The demand was, however, rejected by farmer unions.