Opinion by Pratap Bhanu Mehta

Manmohan Singh secured developmental space for India and positioned India brilliantly. It is capital that we are still living off.

New DelhiDec 27, 2024 12:39 IST First published on: Dec 27, 2024 at 12:16 IST

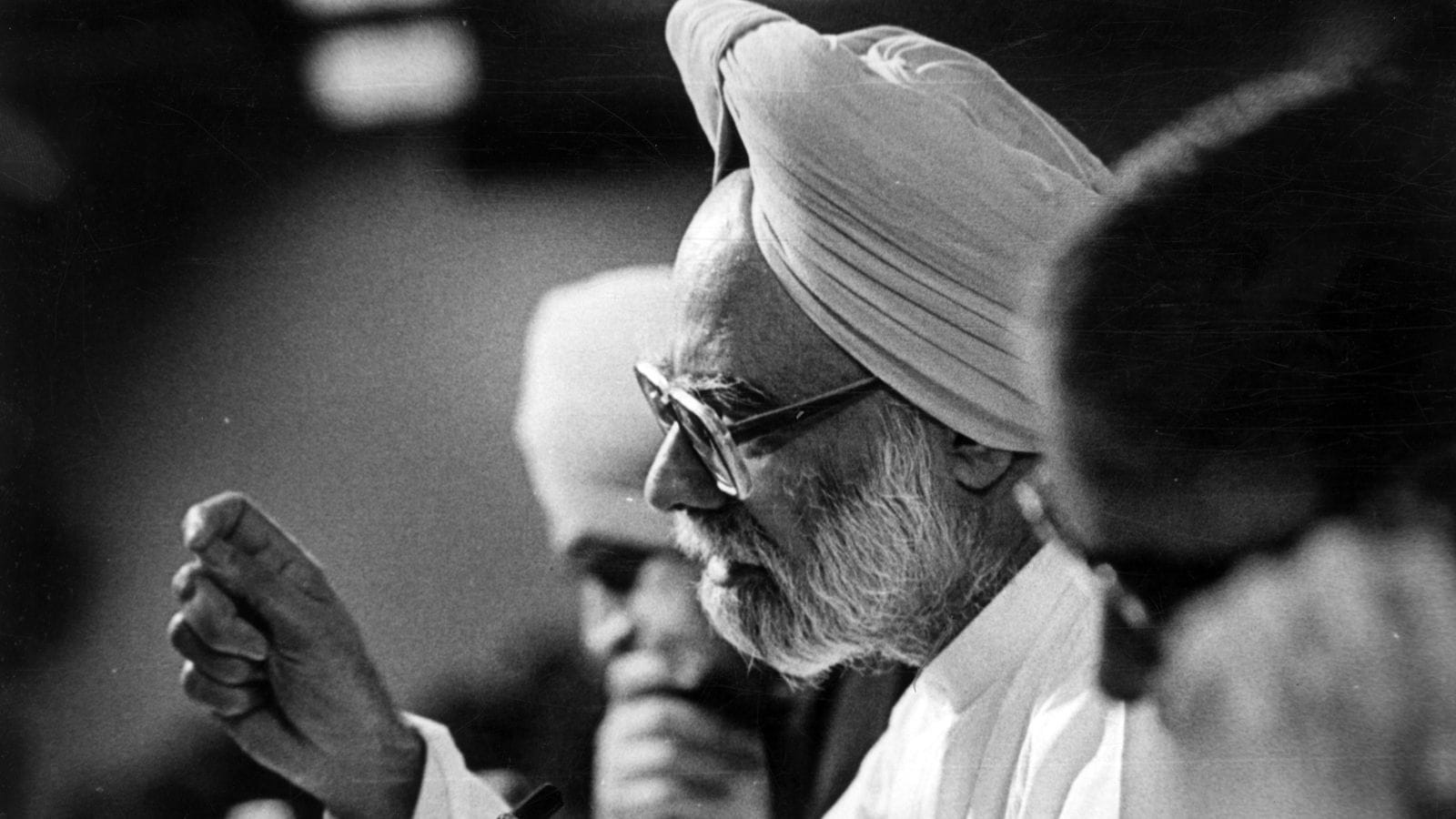

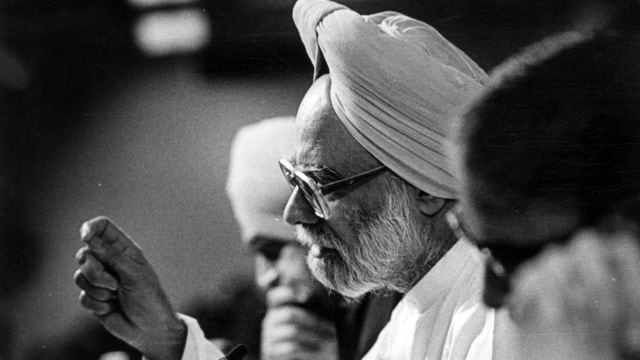

It is a measure of Dr Manmohan Singh’s greatness that his life and influence cannot be described in any conventional categories of political analysis. Assessments of his legacy are apt to be clouded by three short-sighted approaches. One is strictly instrumental, chalking up a long list of economic reforms over which he presided. This list is impressive indeed. He is, arguably, one of the most influential economic policymakers in the annals of history. The second approach that clouds judgment is to see his legacy through the eventual meltdown and defeat of UPA II. He was right that history would judge him kindlier than the contingent political failures of the era. The third mistake, often promoted even by his friends, has a touch of condescension to it. Epithets like “the accidental prime minister” or the “ideal number two man, capable, full of integrity and loyal” — an unbeatable combination — underestimate how he managed to remain his own man and stamp a vision on the world, amidst all the upheavals of bureaucratic and political life.

Like all great men in history, Manmohan Singh’s life transcends the nit-picking accounting of policy successes or failures, a short-term historical reckoning, or simply a focus on his interpersonal relations. What is astounding is that, like all influential lives, his is both a personal marvel and a reflection of the zeitgeist. How did this person, who rose from humble circumstances, whose defining characteristic was an unmatched decency, and who had no political base, end up being indispensable in so many capacities? He was not just a bureaucrat or a finance minister but a defining Prime Minister of India for a decade. In a political culture where the one virtue that is always reliably absent is decency, Manmohan Singh’s ability to hold on to that trait now seems almost saintly. The nature of his power was complicated. In lesser men, it would have bred insecurity or a conniving will to project it. But to be both at the pinnacle of power and hold onto a consistent reticence about it is remarkable.

Singh’s greatness was, in some ways, to embody the zeitgeist in the most graceful way possible. He was one of the greatest Nehruvians. Nehruvian is not so much a set of policy prescriptions, which may sometimes be right or wrong. It is an approach to the world that more deeply prepares India to take its place at the pinnacle of a thoughtful, decent modernity. It was a modernity that was, in political terms, secular, driven by a keen regard for process and consensus, building immense room for real debate, a suspicion of the legitimisation of violence, and a statecraft guided by the application of knowledge. Singh, in the first phase of his life, played the role of an ideal Nehruvian progressive.

But it was in the second phase of his life, when he became the prime minister, that he read the spirit of the age better than anyone else. He read geopolitics after the fall of the Soviet Union remarkably well, secured breakthroughs in our relationship with America and enjoyed an unprecedented bonhomie with China. He secured developmental space for India and positioned India brilliantly. It is a capital we are still living off. His most under-appreciated facet was his understanding of South Asia. The tactical debate over our response to 26/11 has clouded truths he grasped instinctively: That South Asia is not a conventional international relations problem; India needs a long game of tact that understands our neighbours’ fears and learns to manage them. There has simply been no Indian prime minister whose grasp of the region and desire for the long-term goal of strategic alignment of the subcontinent was as acutely sophisticated as his. Not succumbing to the political clamour for vengeance in relation to Pakistan was not a sign of weakness; it was a display of strength that paid immense long-term dividends. The Musharraf-Manmohan agreement was a creative piece of diplomacy that the Congress party did not have the courage to follow through.

Singh’s visionary arc had a clear thread: The psychological and strategic dimensions of liberalisation and globalisation. He had immense confidence in India’s ability to compete. He knew that India could not be influential if it was not part of the sinews of the global economy. In a way, UPA I, with all its flaws, was a workable model for India — liberalisation producing high growth that translated into a new welfare architecture, coupled with strengthening of institutions of lateral accountability like the Right to Information Act. Singh presided over an unprecedented period of growth, decline in poverty, and expansion of infrastructure.

most read

But his brilliant overall strategic vision was overshadowed by a party structure he could not overcome. The biggest mystery about UPA II is not the political relationship between Sonia Gandhi and Singh. It is actually how the Gandhis, for all their seeming monopoly of the party, rather mysteriously acted as if they had lost complete control of it. The corruption scandals in Congress were real. As one senior party leader quipped, Congress is poor, but Congressmen are rich. The political economy of corruption did in not just the Congress Party but India’s economy as well. Pranab Mukherjee’s appointment as the finance minister was a disaster. Singh’s stoic silences as all this unfolded cast a shadow on his own legacy. Congress, as is its nature, never actually projected Singh, its greatest asset. The credit for different elements was parcelled out: Election victories were all Rahul’s; the welfare architecture, including the single most important scheme that saved India, NREGA, was all National Advisory Council. To add insult to injury, Rahul Gandhi humiliated the PM by publicly tearing up a government ordinance, and the party’s stand on Sharm-El-Shaikh cut him to size. The remarkable conceptual vision that held it all together, which was his, got lost. Just read his writings from the period to get a sense of it all.

Manmohan Singh was a PM ideally suited for the “end of history” world — a progressive, technocratic, incremental, centralised, institutions-oriented, trade-focused, globalised, open world, one that has more or less collapsed. His political career is a commentary on how far statesmanship can go without power, decency without compromise, vision without a party. The reputation of every politician of that era, Barack Obama, Angela Merkel, and Singh, has been devoured by the furies of populism that followed. History is a mean avenger. But it is an extraordinary testament to Manmohan Singh’s vision that it is still the most compelling framework India needs.

The writer is contributing editor, The Indian Express

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd