Nov 30, 2024 12:35 IST First published on: Nov 30, 2024 at 12:35 IST

The Places of Worship Act, which was enacted by Parliament in 1991, protects and secures the fundamental values of the Constitution. The law imposes two unwavering and mandatory norms: A bar is imposed by Section 3 on the conversion of a place of worship of any religious denomination. The law preserves the religious character of every place of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. Towards achieving this purpose, it provides for the abatement of suits and legal proceedings with respect to the conversion of the religious character of any place of worship existing on August 15, 1947. Coupled with this, the Act imposes a bar on the institution of fresh suits or legal proceedings.

“The law addresses itself to the state as much as to every citizen of the nation. Its norms bind those who govern the affairs of the country at every level. The state has by enacting the law, enforced a constitutional commitment and operationalised its constitutional obligations to uphold the equality of all religions and secularism, which is a part of the basic features of the Constitution. Historical wrongs cannot be remedied by the people taking the law into their hands…. In preserving the character of public places of worship, Parliament has mandated in no uncertain terms that history and its wrongs shall not be used as instruments to oppress the present and the future.” This is the law, laid out by five judges of the Supreme Court in the Ram Janmabhoomi temple case.

The Supreme Court set aside the following finding by Justice Sharma of Allahabad High Court: “Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 does not debar those cases where declaration is sought for a period prior to the Act came into force or for enforcement of right which was recognised before coming into force of the Act.” The apex court declared that “The above conclusion of Justice D V Sharma is directly contrary to the provisions of Section 4(2).”

To my mind, there is a clear and categorical declaration of law by the Supreme Court concerning the 1991 Act.

The Court held that “Parliament determined that independence from colonial rule furnishes a constitutional basis for healing the injustices of the past by providing the confidence to every religious community that their places of worship be preserved and that their character will not be altered.” It went on to assert: “This court cannot entertain claims that stem from the action of Mughal rulers against Hindu places of worship in a court of law today. For any person who seeks solace or recourse against the actions of any number of ancient rulers, the law is not the answer.” The Court, apologetically, held, “On 6.12.1992 the structure of the mosque was brought down and the mosque was destroyed. The destruction of mosque took place in breach of the order of status quo and the assurance given to this court. The destruction of the mosque and the obliteration of the Islamic structure was an egregious violation of the rule of law.”

Yet, a series of suits and appeals are being filed and entertained with impunity by courts across India, including the Supreme Court, concerning various mosques across the country — from Varanasi to Mathura to Sambhal and even the dargah in Ajmer.

Chief Justices S A Bobde and D Y Chandrachud presided over benches, with other learned judges, that undermined the Court’s previous rulings and cleared the ground for dangerous situations. Likely taking a cue from such interventions, judges at the district and high courts are intervening at the instance of the litigants who themselves are prohibited under the law from filing such suits. Far from furthering it, these judges may well be striking the death knell of secularism. Given this, one wonders if it is possible for a court to be in contempt of itself, especially when it is quick to haul up others for contempt of its orders. Significantly, these suits, and the courts allowing them in defiance of the law, resonate with the politics of those in power. All this at what cost?

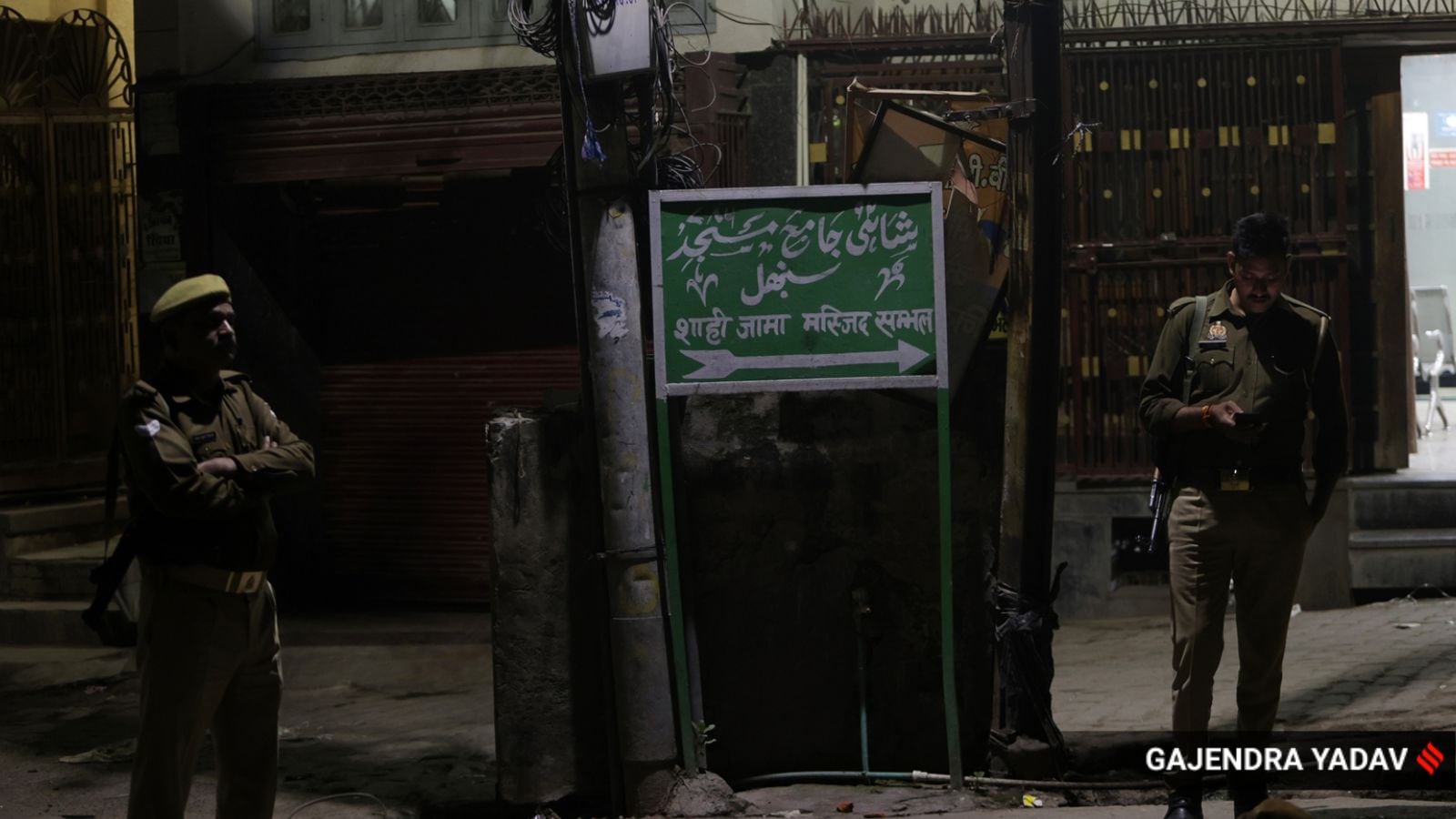

The divide between the majority and minority communities has been widening in recent years. Peace and harmony are being compromised on a daily basis in the name of “love jihad”, “land jihad”, “vote jihad”, bulldozer “justice” and mob lynching. Four innocent lives were lost at Sambhal arguably because of the judiciary’s actions – or the lack thereof. BJP governments appear all too ready to implement questionable orders of the Court with unusual promptness, while orders that help ordinary citizens may take months and years. Perhaps the judicial leaders need to be reminded of the words of great Indians during Constituent Assembly debates.

On May 25, 1949, Sardar Patel, said while submitting the Minority Report: “… it is for us who happen to be in majority what the minorities feel and how we in their position would if we were treated in which they are treated”.

[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S6lBt_ZEqhY?si=r-z2UIiqRv6AE320&w=560&h=315]

most read

B R Ambedkar, fearing that some members were prepared to go to war, said on December 17, 1946: “It will be a war on Muslims. If there is anybody who has in his mind the project of solving the Hindu-Muslim problem by war… in order that Muslims will be subjugated and made to surrender to the Constitution that might be prepared without their consent, this country would be involved in perpetually conquering them.” Again on November 4, 1949, he warned that “… it is wrong for the majority to deny the existence of minorities… The moment the majority loses the habit of discriminating against the minority, the minorities can have no ground to exist. They will perish.”

India needs to develop, socially, economically and politically for the betterment of its people. It does not need violence. Peace alone can lead to prosperity. The sooner those at the helm of the nation — in the legislature, executive and judiciary – realise their duties, the better it is for We, the People.

The writer is a senior advocate practising before the Supreme Court of India