Say what you may, the world has considerably shifted its gaze towards Indian cinema. There’s been a momentous shift in how global audiences consume Indian content, and the fruit of this reinvigorated momentum is the BAFTA Breakthrough India, which is The British Academy of Film and Television Arts‘ flagship talent scheme that aims to support talents from film, gaming, and television.

The list of nine young Indian talents selected for 2024-25 includes writer-director Varun Grover, for his incredibly poised take on the IIT-ian dream in All India Rank, and Christo Tomy of Ullozhukku-fame, for his Netflix documentary Curry & Cyanide: The Jolly Joseph Case. This is no small feat! A selection to the BAFTA Breakthrough program opens a whole avenue of opportunities for these creators — from voting membership and access to BAFTA events and screenings to a year of support, industry introductions and career development, and ultimately a chance to boost their profiles on the global arena.

Neeraj Kumar, Sindhu Murthy, Dhiman Karmakar, Monisha Thyagarajan, Deepa Bhatia, Jaydeep Sarkar and Christo Tomy are photographed by Vikas Gotra for the BAFTA Breakthrough India 2024-25 | Photo Credit: BAFTA/Vikas Gotra

For Varun, the selection primarily serves as a moral boost to indie filmmakers like himself, as it “makes people take you more seriously.” The selection, he adds, also makes the indie filmmaking journey a little less lonely. “You have a cohort — the people selected alongside you. You start bonding, talking about ideas and collaborations. It also opens a big window to filmmakers worldwide, those associated with BAFTA, and others to which BAFTA has access. Every filmmaker we look up to is associated with BAFTA in some way,” he says.

Christo, meanwhile, reflects on the long journey it has taken for him to reach this stage. “After graduating from the Institute (Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute) in 2016, it took eight years to finally work on projects like Curry & Cyanide. This is a significant achievement for me,” he says.

Both the filmmakers seem quite elated over the opportunity to meet imminent filmmakers and pick their brains. “I’m treating this as a year-long mentorship program. I can request specific mentors, speak with them, and learn from their expertise. This — along with access to program teams, screenings, and the library — is a huge resource. My goal is to use this in a structured way to build towards what I want to achieve in my filmography over the next few years. I know who I want to talk to and the knowledge I need for my plans,” says Varun.

Both filmmakers credit the new wave of popular Indian titles in the international arena for paving the way for such broader avenues. “Every year, at least one Indian documentary makes it big at international festivals. This year, for instance, started with Girls Will Be Girls winning an award at Sundance, followed by Nocturnes which also created ripples. Indian documentaries have made it to either the shortlist or the longlist at the Oscars,” says Varun, adding that while the age old perception of Indian cinema being restricted solely to song-and-dance narratives still exists, the diversity of the country’s filmmaking still shines through.

Varun perceives a refreshing energy among filmmakers these days. “Unlike in the ’80s and ’90s, when indie filmmakers worked with limited resources out of necessity, today’s filmmakers have access to more opportunities. For instance, All We Imagine As Light has five international producers and is cutting-edge technically. It’s a contained film — not flashy or trying to dazzle — but it could be in any language and still resonate globally,” he says, adding that such a change was long overdue.

Divya Prabha in a scene from ‘All We Imagine As Light’

Both Varun and Christo observe how it’s a great time for Indian non-fiction, with titles gaining viewership both within the country and worldwide. “Curry & Cyanide was even popular in a state like Kerala, where audiences weren’t open to non-fiction. The barrier of non-fiction being inaccessible to the masses is slowly being broken, and platforms like Netflix and Amazon are supporting these projects,” says Christo.

Varun believes that the commercialisation of the narrative fiction space has led to creators discovering non-fiction as a viable medium for their original stories. “Earlier, documentaries in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s were made in an ‘old-school Doordarshan’ style, where a voiceover narrated the story, similar to the animal world documentaries on Discovery Channel. The narrative wasn’t revealing itself organically, as it does now. This change is a relatively recent discovery that emerged in the last decade.”

This seems to be the result of the “middle-of-the-road cinema movement brought by filmmakers like Dibakar Banerjee, Vishal Bhardwaj, and Anurag Kashyap in North India, directors like Vetri Maaran, Bala, and Pa Ranjith in Tamil cinema, and so on,” Varun adds. He also notes how this is the space that documentaries have captured, with filmmakers realising they could create compelling narratives with limited budgets.

Christo’s mention of the role of streaming platforms in promoting non-fiction steers the conversation to how the backing of a streamer has been perceived as a major factor behind the success of a documentary in the festival circuit. We had previously debunked the role streamers played in The Elephant Whisperers and Navalny’s win, as opposed to All That Breathes’ loss at the Oscars in 2023. Varun agrees that there seems to be no connection between streaming platforms and their success at festivals. “For instance, a documentary like Sarvnik Kaur’s Against the Tide, now streaming on MUBI, or And Towards Happy Allies by Sreemoyee Singh, also on MUBI, has performed fantastically at festivals worldwide. I don’t know much about OTT dynamics, but I can confidently say that some truly outstanding documentaries are being made regardless of platforms.” Christo points out how several titles enjoy a strong festival run, garnering significant recognition, before making their streaming debut.

Christo even credits Netflix’s strong track record of producing impactful non-fiction content in the U.S. and India, something he says played a significant role in promoting Curry & Cyanide. “Their understanding of how to tell this story was invaluable. Moreover, such global reach for a project — it was on Netflix’s Top 10 even in Malaysia and Indonesia — is possible only due to Netflix’s support,” he adds. The director agrees that it seems like streamers majorly go for popular non-fiction genres like true crime, but assures there’s no lack of space for more diverse sub-genres on these platforms. “That said, only a few platforms support non-fiction in a way that ensures the work reaches a larger audience. As a country, India is still warming up to non-fiction.”

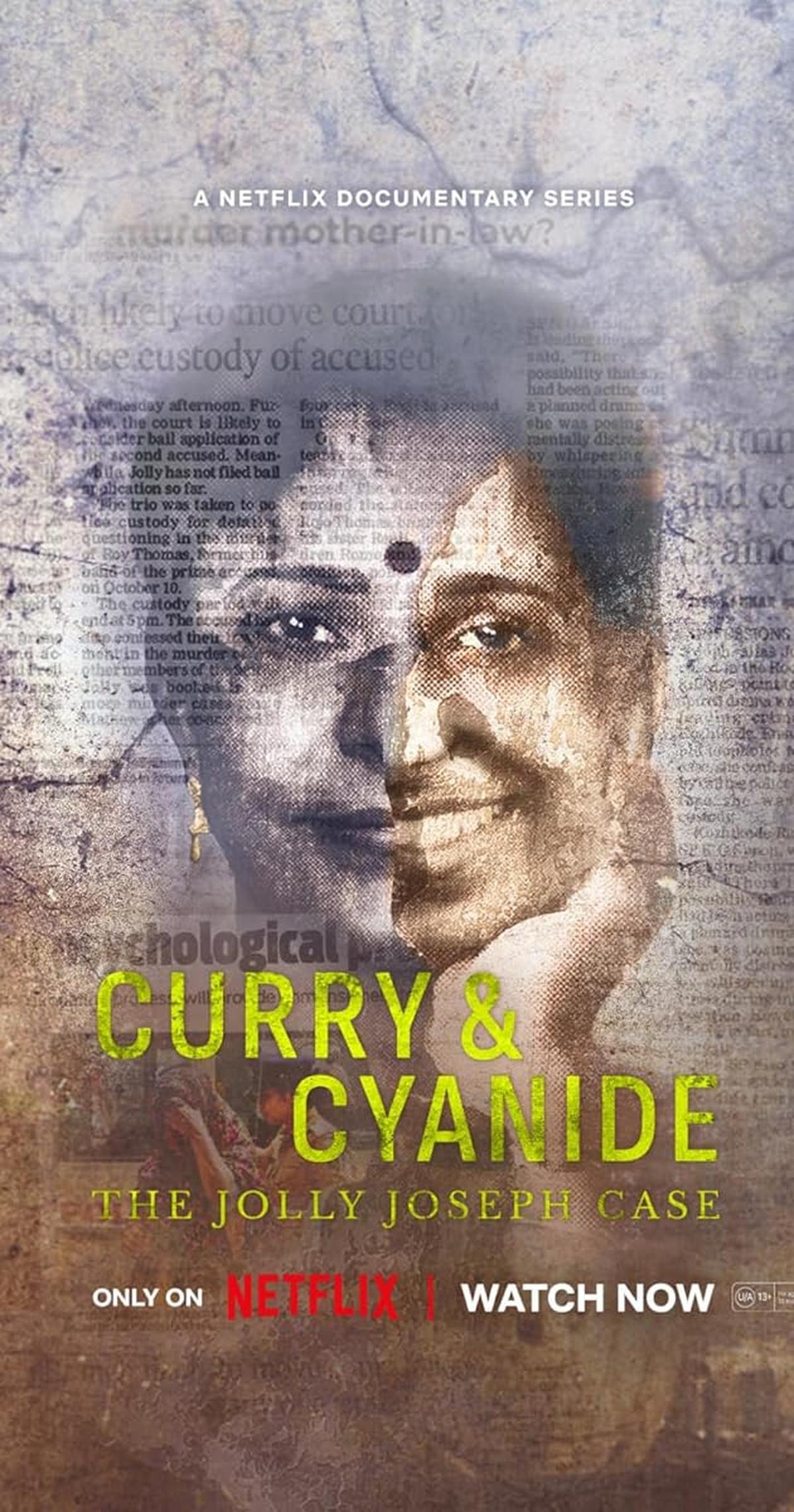

Poster of ‘Curry & Cyanide’ | Photo Credit: Netflix

Remember when titles like Sacred Games and The Family Man broke boundaries and found global audiences? Hasn’t it been a while since we got more of such ground-breaking long-format titles? Having worked on Sacred Games, Varun doesn’t seem sure but agrees with the sense of streaming stagnation that has set in. “Because when something new starts, there’s a lot of space for new ideas. With no precedence, you’re allowed to do what you want. But once things start working and others start failing, people form opinions about what should be made. Then machines enter the space of humans and give data about what works and what doesn’t. Creators are then not allowed to go in a different direction. This limits the choices, themes, and ideas you can touch upon, which becomes a self-fulfilling method to destroy any creative space.” The way to go, according to Varun, is to do what the algorithm isn’t suggesting, or to do the opposite of what it suggests.

In Kerala, on the other hand, long-form storytelling is still in a nascent stage. Christo believes this might be due to low viewership. “This could be one of the reasons why we haven’t seen a breakout series from Kerala in the long-form format yet. Additionally, the theatre market in Kerala is currently in a very healthy state. People are consistently going to theatres to watch films, and in 2024, many Malayalam films have done well theatrically. This model is working successfully for the industry, so the primary focus remains on theatrical releases,” he adds.

After making the breathtaking Ullozhukku, Christo says he has become more aware of the business of cinema. Many producers, Christo says, found the pitch for Ullozhukku lacking in commerciality since it had two female leads, tackled a niche subject, and dealt with themes that some deemed unsuitable for a conservative audience. “For example, people suggested changes like making Anju’s child her husband’s instead of her ex-boyfriend’s because they thought audiences wouldn’t accept it otherwise. Yet, when the film was released, I was pleasantly surprised to see families, including elderly and conservative viewers, watching and enjoying the film.” Nevertheless, the challenges the journey posed seem to have troubled Christo quite a bit. “Now, when I write or develop a story, I think about its commercial feasibility. The challenge lies in finding a balance — creating films that are accessible to the masses and true to the stories I want to tell. This is where my focus is now: achieving that balance.”

Poster of ‘Ullozhukku’ and a still from ‘All India Rank’ | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement and Netflix

When All India Rank came out, many pointed out how the film’s release window, which it shared with titles like Kota Factory, played spoilsport to the film’s success. Varun agrees that he wished he had made the film when he first wrote the script, but assures that such a “once-in-a-blue-moon coincidence” will never happen again. ‘It would require an absurd coincidence — so much so that if it happens again, I’m pretty sure an asteroid will come and hit us on the same day.”

Meanwhile, Varun is currently writing his second directorial feature, which he hopes to start filming next year. He also has Superboys of Malegaon coming up, a film he has written, and Raam Reddy’s The Fable, for which he wrote the Hindi dialogues. “Besides that, I’m working on a graphic novel, a short animation film I’m directing, and a short film as part of an anthology.”

Christo’s heart lies with fiction at the moment, though he says he’s open to “exploring exceptional non-fiction stories whenever they come my way.” The director is currently developing a fictional series for a major platform. “I’m also working on a few feature films — one in Hindi and one in Malayalam. One is an action comedy, and another is a romantic crime thriller.” Christo doesn’t want to do another Ullozhukku. “I would feel truly satisfied when my body of work spans various genres and styles because, ultimately, it’s the story that matters. I want to explore a variety of genres — action comedies, crime thrillers, romantic comedies — and delve into different kinds of narratives,” he says, adding that he is now also keen on international co-productions. “I feel like BAFTA Breakthrough will give me opportunities to connect with people globally and to make projects with international reach.”

Published – November 24, 2024 07:14 pm IST