Protection of minorities is the hallmark of a civilisation. Franklin Roosevelt rightly reminded us that “no democracy can long survive which does not accept as fundamental to its very existence the recognition of the rights of minorities”. The Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on minority rights, starting from the Kerala Education Bill case (1957), has been one that any constitutional court can be proud of. S Azeez Basha (1967) was a rare exception that was widely criticised, with India’s greatest constitutional law expert H M Seervai terming it as “productive of great public mischief”. On Friday, a seven-judge bench, by majority of 4:3, overruled a 56-year-old judgment and laid down the indicia to determine the minority character of an institution that had been left unanswered even by the 11-judge bench in TMA Pai Foundation (2002). In Anjuman-e-Rehmania (1981), a two-judge bench noted these criticisms and referred the matter to the Chief Justice of India to constitute a seven-judge bench. In December 1981, Parliament amended the Aligarh Muslim University Act of 1920 and clarified the doubts about the word “establish” in the long title and preamble of the original Act by deleting it. It explicitly declared in Section 2 (L) that Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) was established by the Muslims of India as an institution of their choice, which had originated as MAO College and was subsequently incorporated.

Chief Justice S R Das in the Kerala Education Bill case had said that minority institutions are primarily for the minority that has established the institution, and there shall be only a “sprinkling of outsiders” in such institutions. However, clarity on this issue came as late as the St Stephen’s (1992) and TMA Pai Foundation judgments. AMU did not have Muslim reservations till 2004-05 — the subject of reservation in aided minority institutions was clarified only in 2005 when the 93rd constitutional amendment inserted clause five in Article 15 and exempted minority institutions from SC, ST and OBC reservations.

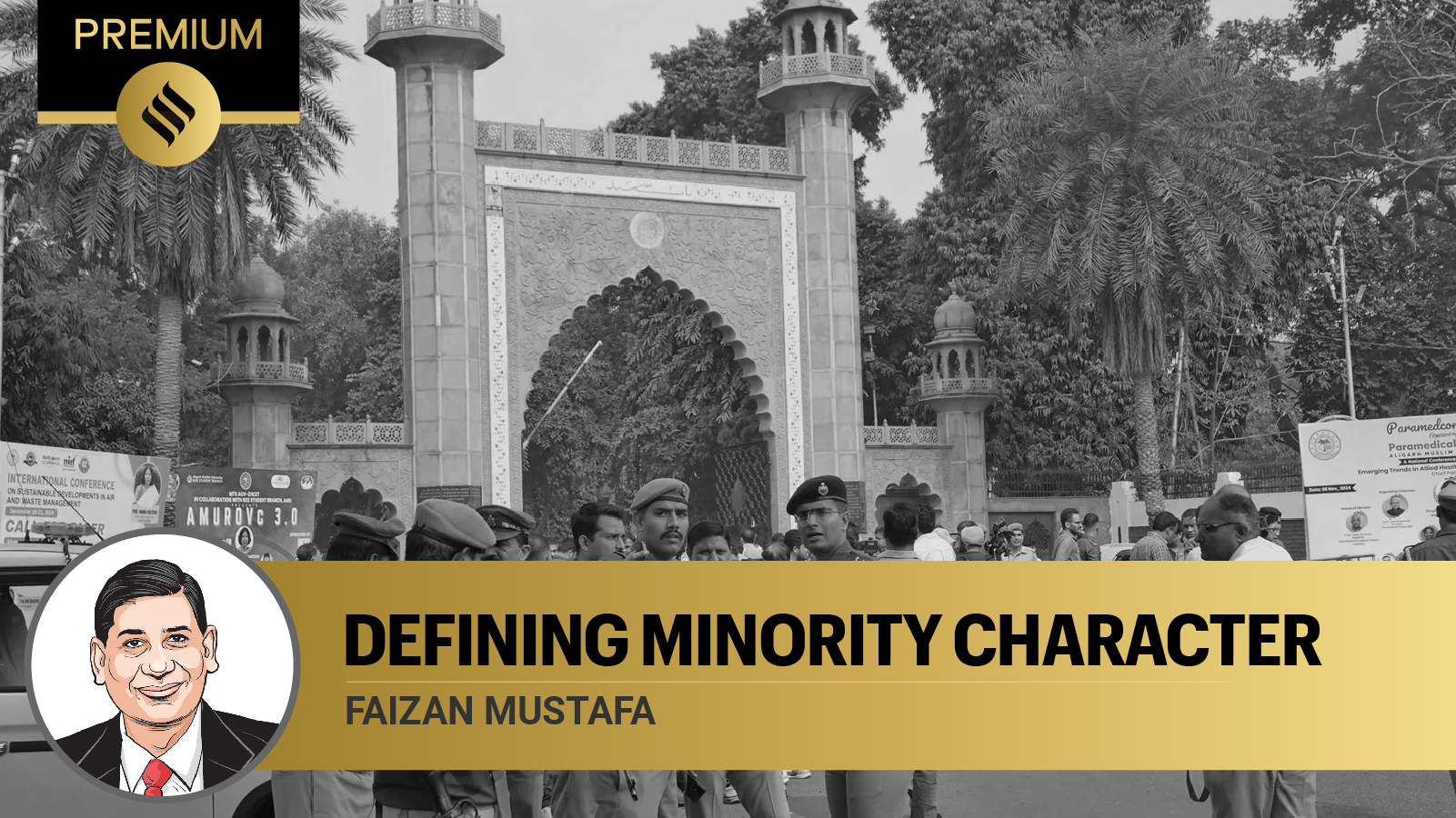

In 2005, AMU first sought the approval of the central government on its new reservation policy, which was confined to MD/MS courses. The central government issued a notification on February 25, 2005, accepting AMU as a minority institution and permitting 50 per cent reservation for Muslims. This was challenged in the Allahabad High Court, which declared a few provisions of the 1981 amendment as unconstitutional due to what the court termed as “brazen overruling” of the Supreme Court’s 1967 judgment.

In 2019, a three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi referred the matter to the seven-judge bench. It delivered its landmark verdict on the last working day of CJI D Y Chandrachud. The dissenting judges found fault with the 1981 reference, as ordinarily two judges cannot directly refer a matter to a seven-judge bench if the CJI is not on it. The Court rejected the argument that Muslims were not a minority in 1920 or did not think of themselves as a minority. It said the group must be a minority on the commencement of the Constitution and pre-Constitution institutions are also entitled to protection under Article 30, even when founding a university.

The 1967 judgment by then Chief Justice K N Wanchoo took a formalistic and narrow view of the term “establish” in Article 30 and attached undue importance to the long title, preamble and other provisions of the AMU Act, 1920, to return the finding that the university was neither established nor administered by the Muslim community. This excessive reliance on the 1920 Act did not find favour with the seven-judge bench, which has observed that courts must pierce the legislative veil to find the genesis — who conceived the original idea, who collected funds and who took necessary steps to get governmental approval. Mere statutory incorporation cannot ipso facto lead to a loss of the minority character of an institution. The courts interpret the statute holistically to find out if AMU relinquished its minority character on incorporation. The Court also held that Basha, after recognising the efforts by the Muslims between 1877 and 1920 to establish the institution, was wrong in ignoring history.

The majority of judges rejected the argument against AMU’s minority character because it was mentioned as an institution of national importance in the Constitution. The Court said Entry 63 of the Union List empowers Parliament to enact regulations in respect of AMU and does not amount to the surrender of its minority character. The CJI observed that the terms “national” and “minority” are not at odds with each other. A minority institution can also be one of national importance. The dissenting judges, on the other hand, considered this an important facet of the university’s non-minority status. Relying on earlier judgments, the CJI held that the admission of non-minority students, financial contribution by non-minorities, governmental grant of land or aid, degree recognition, and non-minorities’ presence in the administration does not change the character of a minority institution.

In the most liberal interpretation of Article 30, the CJI observed that to determine minority character, it is not necessary that the administration must be vested in the minority itself. The right to administer is the consequence of the establishment of the institution. “To do otherwise, would amount to converting a consequence to a pre-condition,” the CJI opined. Widening the ambit of Article 30, the Court also refused to attach much significance to either the provision of religious instruction or the centrality of religious buildings, like the St Stephen’s College church or AMU mosque. The only flip side of the majority opinion is that like in Basha, it has accepted the possibility of minorities giving up or surrendering their right to administer. Constitutionally, fundamental rights cannot be waived. In Ahmedabad St Xaviers (1975), the Court held that rights of future generations cannot be surrendered.

A three-judge bench, which will now determine the minority character of AMU, will no longer be constrained by Basha. It will be bound to apply the indicia laid down by the majority on November 8. Since the Allahabad HC’s judgments of 2005 were also based on the apex court’s 1967 judgment, they no longer have much significance, though appeals against them are pending with the Supreme Court.

The writer is vice-chancellor of Chanakya National Law University, Patna. Views are personal