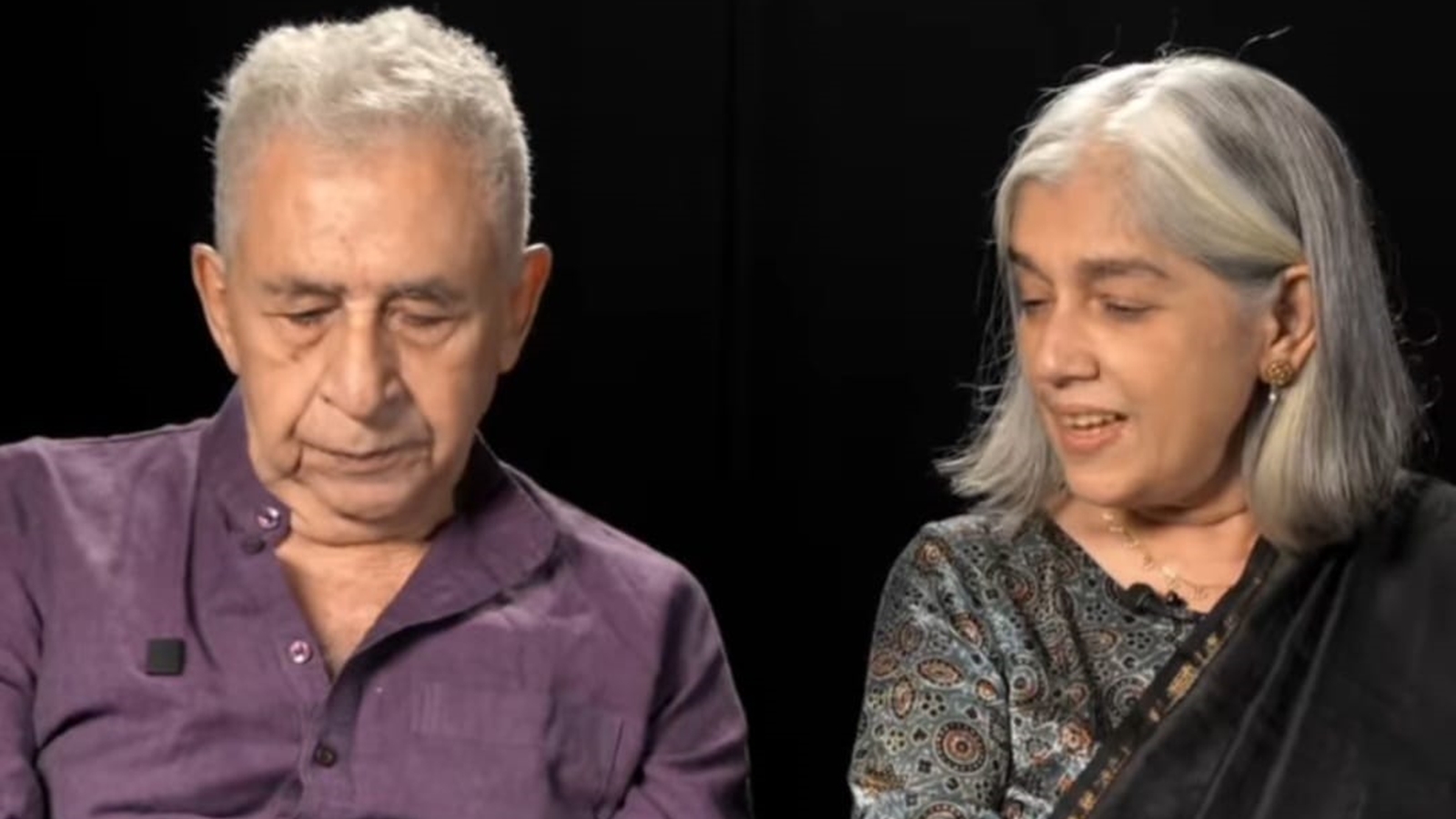

It was refreshing that Naseeruddin Shah read Dastaan-e-Bhanwar, on the life of Bhanwari Devi and other hapless victims of patriarchy, on the opening day of the annual Prithvi Festival in Mumbai, and not his wife Ratna Pathak Shah. The latter would have been the predictable choice.

In simple terms, dastaan means a story. But this was no grandma’s bedtime tale. Nor was it like traditional Persian dastaans, full of swashbuckling heroes. “There are no bees and butterflies in the story I will narrate,” disclaimed the actor before setting forth to describe an indomitable village woman, a victim of a brutal gang rape, who stood up to a system loaded in favour of men. Older generations in the audience might have heard about the uneducated Bhanwari Devi’s fight against child marriage in rural Rajasthan and the terrible price she had to pay for it. But public memory is short and today’s generation may not know who she is. So her dastaan merits reiteration.

In a 45-minute monologue, Shah traced Bhanwari’s life and how it changed the course of women’s agitations in many ways. As was the norm then, Bhanwari was only about six years old when she was married off to nine-year-old Mohanlal Prajapat from a potter’s family, and over the years, became a mother to four children. However, what was rare and unusual was her becoming a grassroots worker for a women’s development project run by the Government of Rajasthan. Known as a saathin, Bhanwari took her job of promoting government-introduced health and social measures seriously, making her village proud.

But when she dared to discourage a Gurjar family from marrying their nine-month old daughter to a 12-month old boy, she antagonised a powerful section of her village. Undaunted, she complained to relevant authorities who stopped the wedding from happening on Akha Teej, considered an auspicious day. To circumvent the law, the family simply shifted to another house and conducted the marriage.

Thereafter, furious that Bhanwari had dared to bring the police to their doorstep to stop an age-old tradition, the Gurjar family caused her family to be ostracised, preventing anybody from buying the pots they made and disallowing anybody to sell milk to them. Bhanwari was forced to even give up her government job. Worse, on September 22, 1992, while she and her husband were working in the field, five men descended on them at dusk, beat up her husband till he fell unconscious, and gang-raped her.

Shah narrates how a lone, lower-caste, traumatised woman had to then run from pillar to post to have the perpetrators punished. Did she succeed? Initially, the accused were put behind bars but as the case against them proceeded, they were able to wriggle their way out, with the Jaipur District and Sessions Court acquitting all five accused on absurd grounds. The judge pronounced that it was not possible for her to be raped when her husband was present. Surely, he would not have stood by as a passive observer. Secondly, men don’t have physical relationships with lower-caste women. And thirdly, the men were too old to commit such a crime. That a judgment could be given on the basis of pure assumptions showed how deep the rot was and what Bhanwari Devi was up against.

What is even more disconcerting, pointed out a visibly angry Shah, is that Bhanwari’s was not an exceptional case. Similar incidents happen on a regular basis across the length and breadth of the country: Mathura, a tribal woman, was raped at a police station in Gadchiroli, Nirbhaya was gang-raped in a Delhi bus and Bilkis Bano gang-raped in Gujarat. Even six-month old babies are brutalised by male lust. The papers report such horrific incidents all the time (Shah’s narration had a glaring omission. There was no mention of the recent rape of a doctor in R G Kar Hospital in Kolkata, which showed how unsafe women continue to be at the workplace, despite the Vishaka guidelines that were framed after the Bhanwari Devi rape case).

Most times, the common man shrugs off incidents like these with a “Such things happen” attitude, said Shah. “But it could happen to someone in your family too,” he warned. Yes, it could but that is not the only reason why we must never put these issues on the back burner. Bhanwari Devi did not give up her fight against an all-powerful establishment merely to get justice for herself, but to prevent other women from being subjected to similar ordeals.

Unfortunately, though, the Ashok Lal-written Dastaan-e-Bhanwar somehow fails to make for a gripping dastaan. The story sounds jaded despite being bolstered with poems by Faiz Ahmad Faiz and other activist-poets. When you write about pressing issues for the stage you cannot sound like a columnist for the edit page of a newspaper. The style of writing needs a certain style and flair suitable for a monologue on stage.

I have marvelled at Shah’s ability to enthral viewers in monologues earlier, sat mesmerised through his reading of Khalil Gibran, but this particular show left me unmoved.

Chowdhury is the author of Dev Anand: Dashing, Debonair (2004)