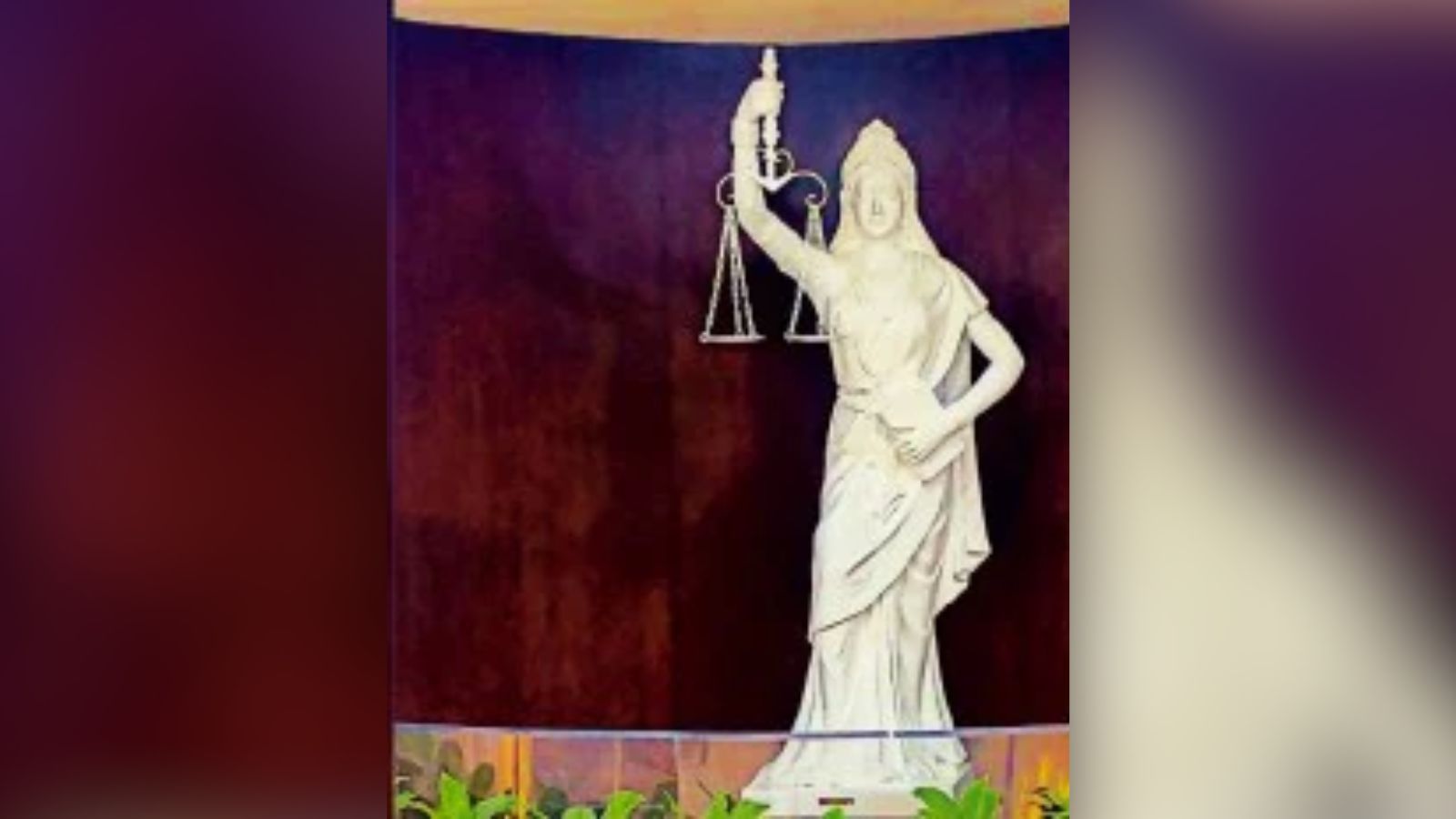

Lady Justice in India has opened her eyes. Hopefully, she will behold herself too, as there are concerns that the Indian judiciary has to address immediately. However, the symbolic changes made to a statue of Lady Justice placed in the library of the Supreme Court, communicate something deeper, which is foundational to the idea of justice itself.

That the violent, retributive approach to justice, symbolised by a sword in the hand, has been replaced by modern progressive values as enshrined in the Constitution, is welcome. If we are to analyse justice in a society, as John Rawls said, we must look not at the particular acts of individuals, but at political, economic, and social institutions. What principles should govern our social and legal institutions? What guidelines should we follow while designing our institutions if they are to be just?

In Rawls’ view, these have to primarily be fairness and impartiality, as illustrated in his proposal of “the veil of ignorance”. He argues that the parties in a just society have to be necessarily fair to everyone, where a person would not choose principles that favour the rich over the poor, Hindus over Muslims, one gender over the other, or one caste or race over another. In short, the “veil of ignorance” would force everyone to choose principles that would be perfectly just to everyone.

The laws and institutions of the society must embody justice or they should be reformed. “Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of systems of thought. … laws and institutions no matter how efficient and well-arranged must be reformed or abolished if they are unjust. Each person possesses an inviolability founded on justice that the even welfare of the society as a whole cannot override,” wrote Rawls, in The Theory of Justice.

Early liberalism was of the view that the best society is one in which individuals are left free to pursue their own interests and fulfilment as they choose. While contemporary liberalism has only retained this fundamental commitment to individual liberty, it has also added an awareness of the extent to which economic realities can indirectly limit an individual’s liberty.

The choices of the poor person are restricted by that person’s poverty whereas wealth and property endow the rich with a much wider set of choices and powers not available to the poor. Justice must open its eyes to such social realities. Thus, the new representation of Lady Justice can be seen as a welcome step towards a conceptual reformation of the Indian judiciary.

Even when impartiality — that everyone is treated equally before the law as symbolised by the covered eyes of Lady Justice — is considered an essential aspect of justice, the judicial system cannot be so impartial and institutionalised as to turn morally blind eyes towards political apathy or the vulnerability of individuals or classes.

Justice, as realised in the cases of Father Stan Swamy, who was afflicted with Parkinson’s, or a wheelchair-bound Professor G N Saibaba, is seen by many as instances of injustice. The judiciary should be able to decipher the intentions of the executive (for which neither eyes that are merely open, nor a hand that holds the Constitution, are enough) while dealing with political prisoners like students, activists, or vulnerable old men.

Even as presenting Lady Justice with open eyes and in a decolonised form is a welcome symbolic gesture, there are risks associated with this move. It may even strip justice and the legal system of their transformative potential. A new representation of justice using cultural hegemonic symbols hardly depoliticises justice.

Opening of eyes could challenge the foundation of justice, and impartiality. Further, if enough precautions are not taken, especially in a society with deep political and communal divides, where political leaders identify individuals by their outward appearances, or what they choose to eat.

One needs to remember the words of B R Ambedkar that a good Constitution in the hands of bad men would amount to nothing. Constitutional morality is more important than the Constitution.

One should also remember that having the eyes closed is not necessarily a reason for not seeing or responding to instances of injustice. In the Mahabharata, Gandhari, who chose to remain blind, is not accused of being party to injustice, in the way that each able and powerful man who witnessed the disrobing of Draupadi and chose to remain silent, is. One can choose not to see and be blind, even when eyes are wide open.

The Constitution in the hand of Lady Justice doesn’t necessarily mean a progressive approach would be taken towards justice, just as a sword in her hand doesn’t necessarily mean violence. Nor would open eyes mean that justice would be served better.

This is an occasion for civil society to not only ponder on the concept of justice, but also how it is realised in the complex cultural and political milieu of India. The symbolic changes made to Lady Justice should not be reduced to a mere political and fashion statement.

Sunitha V is assistant professor and head, and Sebastian is assistant professor, at the Department of Philosophy, Madras Christian College