The gruesome murder of Baba Siddique, former Maharashtra minister and an active politician in Mumbai, has put the spotlight on public order and safety. The involvement of an organised criminal gang has brought back memories from the 1990s when the open presence of such gangs was much more common. The rich and famous of the metropolis could not celebrate any festival for fear of extortion calls from gangsters who ruled the city for nearly a decade, before being either gunned down by police officers or arrested under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act (MCOCA). The law was brought specifically to control the violent, nefarious activities of gangs.

Encounter killings by the police slowly faded away in Mumbai due to judicial scrutiny, though the practice had many admirers among the media and citizens who were tired of daylight murders on the street. However, some other states battling crime syndicates started emulating the debatable “encounter” culture, an indication of the failure of the criminal justice system in the country. Instead of investing in an efficient, technologically advanced police, forensic laboratories and judicial infrastructure, they opted for the quicker but decidedly damaging option of an “encounter”.

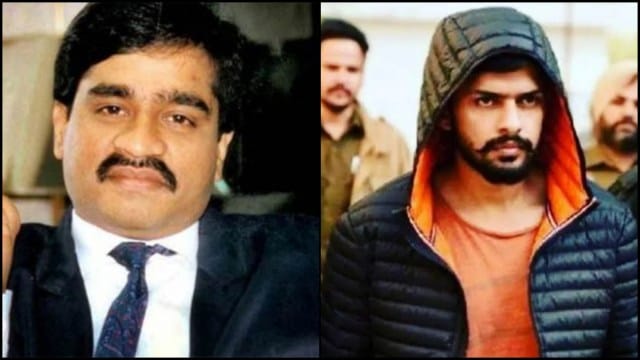

Mumbai’s criminal gangs started with bootlegging and gambling and slowly graduated to smuggling liquor, silver, gold, chemicals, ball bearings and narcotics. In a desire to earn the goodwill of citizens, they acted as modern-day Robin Hoods organising Ganpati poojas, getting medical aid to the sick and disabled, and providing financial help to the needy. But behind the scenes, they would identify possible targets, recruit footsoldiers and use country-made and sophisticated weapons to strike. Threats to those who objected to their activities were also common. With unprecedented unemployment during the early ’80s due to mill strikes in Mumbai, young, jobless men started joining gangs for easy money. Haji Mastan, Karim Lala, Varadarajan Mudaliar, Iqbal Mirchi, Dawood Ibrahim called the shots.

From smuggling, these gangs soon moved on to real estate as it was a hugely profitable business for land-starved Mumbai. A land dispute takes around 20 years in civil courts to settle, but less than twenty days in the kangaroo courts of gangsters. Businessmen, builders and politicians began approaching them to settle scores, leading to a boom in organised crime. They would take to guns if the disputed party did not come to the table. Local boys also started joining the emerging gangs of Arun Gawli and Ashwin Naik. Soon, protection money became common. Businessmen, film personalities and industrialists would receive calls to pay a regular amount to ensure their safety and that of their property. Fear of violent gangsters, little faith in law enforcement agencies, and huge pendency of disputed cases in courts led to the mushrooming of the “quick dispute settlement mechanism”.

The Babri Masjid demolition saw Mumbai gangs taking sectarian tones. Chhota Rajan, a member of Dawood’s gang, broke away and formed his own crime syndicate based on religion. While Dawood fled to Dubai and later to Pakistan, Chhota Rajan frequently changed locations till he was finally arrested from Indonesia in 2015.

Organised criminal gangs loosely imitate corporate structures. A member is assured of monthly payment on the basis of his involvement in criminal activities and specific “operations” undertaken. Loyalty is the strongest common denominator and is cultivated by providing legal help when needed and looking after the families of those arrested or killed in police encounters. The gang leader surrounds himself with a core loyal team who pass on instructions to the field operators who barely ever see their “lord and master”. A strict hierarchy is maintained and a need-to-know policy ensures that when police arrest a gang member, he can disclose very limited information. Beyond money, it is the fierce sense of loyalty and, lately of religion, that is exploited by the leaders. Absurd as it may seem, some of the syndicate members now believe that they are acting in the interest of the nation. Motivation to join these crime syndicates ranges from financial gains to feel-good factors in the name of religion and the nation.

The fact that Lawrence Bishnoi’s gang is active despite the chieftain having been in prison for about a decade has led credence to the theory that he has the blessings of powerful politicians and the notion that his Canada connections allow him free play in India. Whether Mumbai Police will be able to collect credible evidence about the involvement of the gang and prove that the conspiracy to murder Baba Siddique was hatched from within the Sabarmati prison is yet to be seen. In this regard, the Ministry of Home Affairs’s order under Section 268(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CRPC)/Section 303 of Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) has become very controversial as it does not allow state police to move Bishnoi to their headquarters for questioning. It has further fuelled speculations about political patronage of gangsters, a claim that is not new.

The Vohra Committee established in 1993 to study the activities of crime syndicates had concluded that they had “developed significant muscle and money power and established linkages with governmental functionaries, political leaders and others to be able to operate with impunity”. In his report, N N Vohra remarked that some of the members “seemed unconvinced that Government actually intended to pursue such matters.”

Fast-tracking the trial of cases against organised crime syndicates and political parties, and politicians determinedly staying away from criminals is one way forward. Corrupt bureaucrats and police officers with vested interests in these gangs too need to be identified and weeded out. If we have to put an end to the resurgence of violent crime syndicates in Mumbai and India, now is the time — not through encounters, but by investing in an effective criminal justice system. But the question remains: Do the central and state governments have the determination to root out organised criminal gangs? Will they follow due process or compromise by taking the quicker route for applause from citizens, unmindful of the damage that it can cause to the rule of law and the nation?

The writer, an IPS, was Chief of Crime Branch, Mumbai

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 16-10-2024 at 16:50 IST