One of my earliest memories of meeting Professor G N Saibaba, or Sai, as some of his friends called him, was at his home in the Gwyer Hall hostel of the Delhi University’s north campus. The first time I went there, I passed through the main entrance, crossing several rows of rooms, and remember hearing a Hindi scholar reciting a Dinkar poem in one of them. On the extreme end of the hostel was Sai’s official residence, allocated to him as the hostel’s warden. Later, when my visits became more frequent, I started using the back door that directly led to his residence. When I met him there, we had already known each other for some time. But from 2007-08 onwards, this acquaintance turned into something deeper. It was a tumultuous time, a time when the Maoist movement was attracting a lot of headlines. Earlier, as someone who had travelled through Bastar, when one returned with stories, editors were simply not interested; they dismissed it as the “Warangal” problem. But now, it was where everyone wanted to go — the then Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, would soon call it India’s biggest internal security threat.

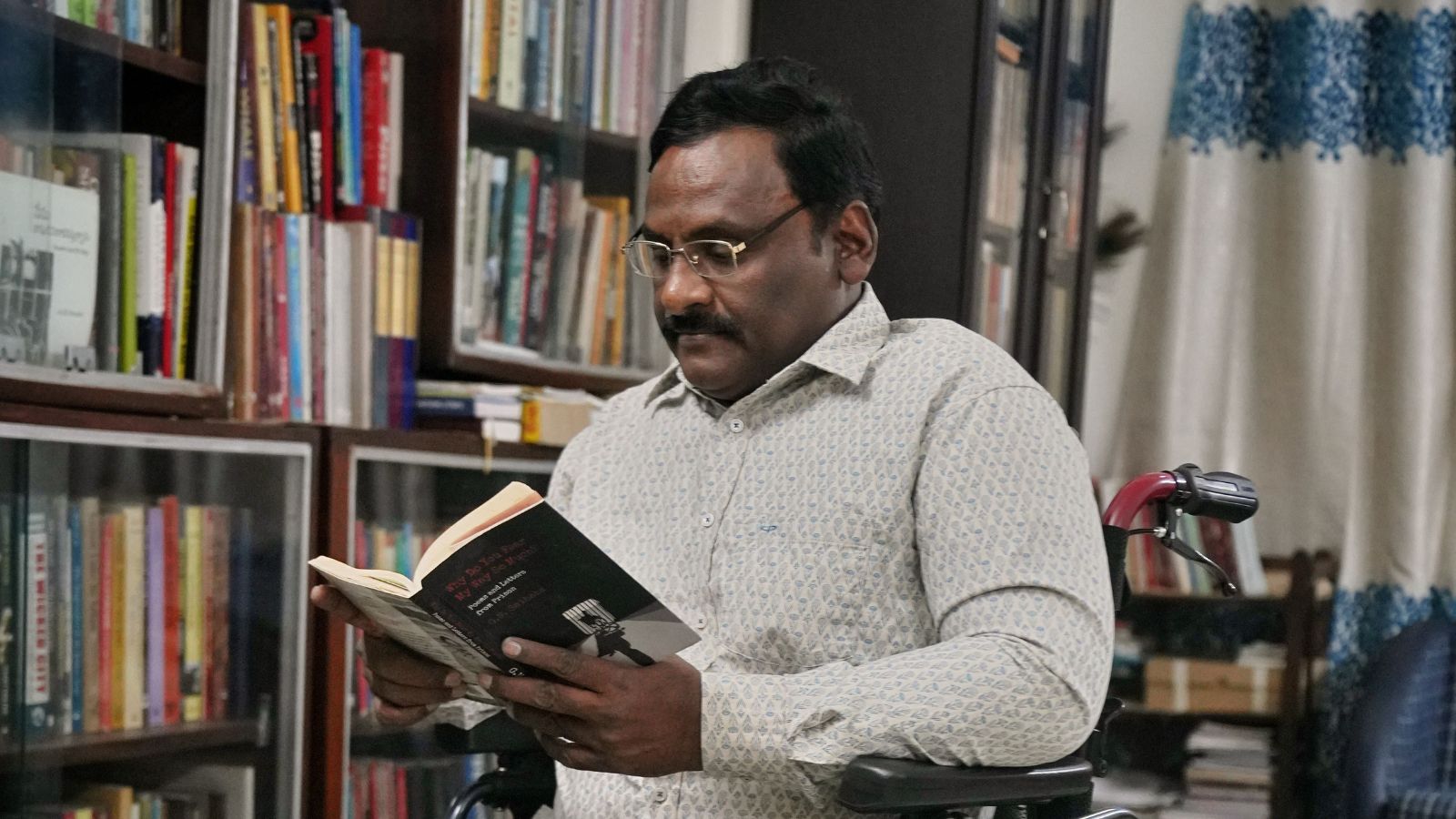

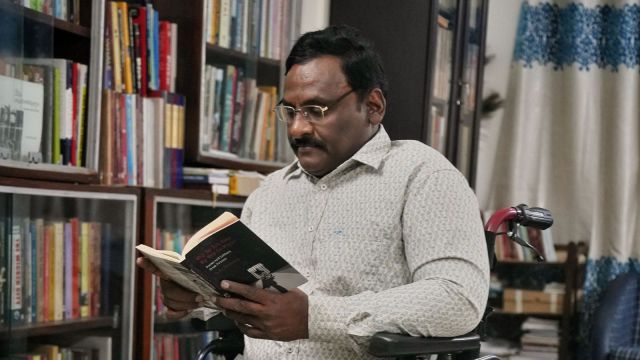

But that would come later. In that little quarter, in whose front room Sai’s daughter, Manjira, always finished her school homework, there was so much to talk about with a man who would push himself into the room on his wheelchair and smile and look at you with his penetrating gaze. The spot where he usually placed himself in the room had a steel book rack nearby that was full of books and pamphlets on tribal rights, political prisoners, and how big corporations were usurping the land of the Adivasis. Sai’s wife, Vasantha, would appear with tea, and he would take out his packet of Gold Flake cigarettes, offer it to me and keep on talking about what he thought I should know as someone interested in the “movement”. He remembered everything, and would dole out names and dates and complete information about an event in a matter of a few minutes.

My travels to the Maoist heartland also increased around that time. There is a way of grief that I came across for the first time in Bastar many, many years ago. Over the corpse of an Adivasi man, killed by state mercenaries, his wife stood in absolute silence, her arms raised behind her head, her face contorted. There was a quiet dignity to that grief; and also surrender to the terrible circumstances of their life, having been caught in a war between the Maoist guerrillas and the Indian state. That day, as I watched that woman, something inside me changed, which I could not contextualise at all. That happened later, when Sai introduced me to a spectrum of people, some of whom became close friends. He knew all of them, from places like Nagpur and Adilabad. Their eyes lit up when they heard Sai’s name and their doors opened up for a weary traveller like me, always on a tight budget. One of them happens to be the lawyer Surendra Gadling, who is still in prison in the Bhima Koregaon case.

I had a curiosity about the movement; I was intrigued by the life of Maoist leaders like Anuradha Ghandy who came from upper-class backgrounds. I wanted to know about people who had left comfortable lives and their loved ones in pursuit of an ideology. With Sai’s help, I travelled near and far, and got in touch with their families. In Adilabad, I met the family of Peddi Shankar, the first “martyr” of the People’s War Group, who was killed in police action in 1980; I was distraught to see that even after so many years, the lives of Dalit families like theirs had hardly changed. In neighbouring Warangal, I spent hours with Somanar Samma, half of whose family had joined the Maoists (her daughter was married to senior Maoist commander, Pulanjaya) and had all died by the time I met her in 2010. I met the mother of Gajjala Ganga Ram, an engineering graduate, who died in 1981 after a hand-grenade exploded in his hands — his sister, I was told, was still with the Maoists. I met the families of other leaders like Sande Rajamouli and Wadkapur Chandramouli, sitting in small drawing rooms, as a father or mother reminisced about sons and daughters they had not seen in years or would never see. By this time, I had in my head an encyclopaedia of sorts on the movement. In fact, one day, Sai was surprised when I figured out the name of the slain Maoist leader, whose partner, Maase, featured in Arundhati Roy’s essay on the Maoists.

The same year, the government launched Operation Green Hunt in Chhattisgarh and elsewhere. The journalist, Hem Chandra Pandey, who was killed by the police along with Maoist leader, Azad, became one of the collateral damages of the operation. I remember meeting Sai and a few other friends at his quarters on the day Pandey’s body was brought to Delhi. Sai was distraught — he had been hoping that there would be some negotiation between the Maoists and the government. But with Azad’s death, since he was killed before he could discuss the terms with the Maoist leadership (with Swami Agnivesh as interlocutor), that opportunity was lost as well. Earlier that year, I had broken the story of how Congress leader Digvijaya Singh, was in touch with a jailed Maoist ideologue, through a Congress leader from Hyderabad (this was a time when Singh had openly accused Chidambaram of “intellectual arrogance”). But with Chidambaram’s reluctance, and the certainty of Operation Green Hunt, that window also closed. A year later, when my book Hello, Bastar was launched in Delhi, Sai was there, and as Digvijaya Singh came down the podium, Sai spoke to him, urging him to intervene on behalf of the Adivasis whose lives were getting badly affected by the violence of Salwa Judum.

A few years later, Sai was arrested. We had not remained in touch like before. By that time, I had my own story of exile from Kashmir to tell. Sai knew about it and he also knew that I had disagreements with him on his engagement with Kashmiri Islamist hardliners like Syed Ali Shah Geelani. But to his credit, he never let that come in the way of our friendship. My last meeting with him was just before his arrest; I told him about a woman Maoist and that I wanted to tell her story. He looked at me and smiled; he said: “Why not! Her story is yours as much as it is mine.”

As I came to know of his death, I remembered that smile. I posted a little message on X, which was met with the usual flurry of labels like “Urban Naxal” from anonymous handles — the people behind these cannot even point out Bastar on India’s map. Today, I wanted to tell them something: They should try and meet CRPF soldiers who have served there. They may fight and kill Maoists, as is their duty, but I have also found them deeply aware of the plight of the Adivasis there. The first warning against Salwa Judum, they may not know, was sent to the Centre by one of their officers.

We have lost Sai — and we must have no hesitation in saying that it is because of the brutal incarceration he faced before being acquitted of all charges. Let us hope and pray that his death (and life) prompts the judiciary to go back to the raison d’être of the Supreme Court; let us hope that it results now in the release of Surendra Gadling, Umar Khalid, and many others whom this country’s justice system has utterly failed.

Pandita is the author of Hello, Bastar: The Untold story of India’s Maoist Movement.

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 13-10-2024 at 17:58 IST